Harriet Beecher Stowe and the Fugitive

by Jeff Worley

John Andrew Jackson’s Great Escape

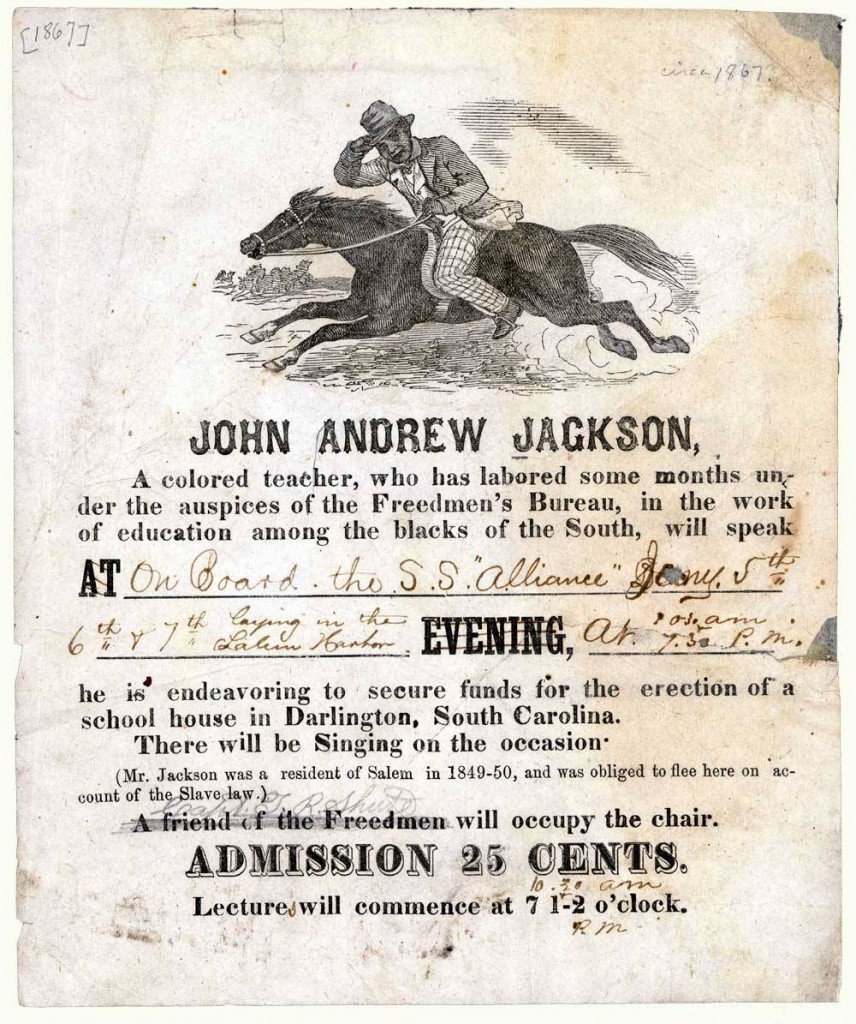

A poster designed to advertise an 1862 speech by Jackson in order to raise funds for a freedmen’s school. Image courtesy of American Antiquarian Society.

John Andrew Jackson was born into a brutal life of labor and abuse in what is present-day Lynchburg, South Carolina. Even as a boy, he was whipped or beaten—for praying, not obeying fast enough, or for no reason at all. Most horribly, he saw his sister whipped to death at the instruction of the plantation owner’s daughter.

He found some brief happiness with Louisa, a young woman who lived on a nearby plantation. He married her, but when she and their daughter, Jenny, were sold to a plantation owner in Georgia, Jackson’s devastation knew no bounds, and he resolved to use the rapidly degrading sanity of plantation owner Robert English to his advantage. With his owner collapsing into dementia, oversight and discipline on the plantation were lax. Jackson began to hatch a plan for escape. If he couldn’t join Jenny and Louisa, he would escape slavery entirely and perhaps someday, somehow, be reunited with them.

Jackson traded some chickens for a pony that a neighboring slave had somehow obtained. He hid the pony deep in the woods. On Christmas Day, he took advantage of the customary three-day holiday and fled on horseback for Charleston. He had often been to Charleston to drive his master’s cattle to market and knew the route well. Unlike many fugitives forced to brave unknown terrain, Jackson’s flight to Charleston was through familiar turf. From Charleston, he hoped to head north, for permanent freedom.

Where did he belong?

In Charleston, Jackson had a tense encounter that could have led him back to the plantation. As he was walking past the docked boats, several dockworkers asked him bluntly if he was a fugitive slave and asked to whom he “belonged.” Since he couldn’t plausibly pass as a Charleston slave and certainly didn’t want to admit to being a fugitive, Jackson said he “belonged to South Carolina.” His clever and unexpected response may have perplexed his interrogators—and they let him be.

When Jackson found a ship heading to Boston, he tried to board, but the crewmen refused to let him. That night, when he was sure no one was on the ship, he hid in a five-by-three foot box on a lower level of the vessel. Eventually, on the high seas, the crewmen found him and threatened to unload him on the next ship. There never was another ship, and Jackson made it to Boston safely.

From Boston, he went on to settle in Salem, Massachusetts. Rather than live underground, Jackson chose to keep his name and live openly. He worked to raise funds with Northern abolitionists who were willing to help him negotiate freedom for the wife and baby daughter he had left behind.

But this plan was doomed to failure. Before he was able to raise sufficient funds to purchase his family’s freedom, the passage of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act effectively forced him to flee again, this time north to Canada with the help of the increasingly organized Underground Railroad.

Brunswick, Maine, and his fateful night with Harriet Beecher Stowe, was perhaps his last stop before he made it to Canada and, finally, to freedom.

ONE COLD NIGHT IN BRUNSWICK, MAINE, in late 1850, Harriet Beecher Stowe hid a fugitive slave in her house. She and her children listened with great interest to his stories and songs, and sympathized with him when he told her how much he missed his wife and daughter back in South Carolina. Stowe even inspected his back, which was covered with scars from numerous whippings. The man left early the next morning and, with help from the Underground Railroad, made it safely to the town of Saint John in New Brunswick, Canada.

“He was not the first fugitive she had ever met, but he was the first—and only—runaway slave that Stowe harbored in her own home,” says Susanna Ashton, whose special research interest is nineteenth-century American literature. “She willingly did this despite the draconian penalties imposed for such behavior by the Fugitive Slave Act of eighteen-fifty, which had been passed only a few weeks earlier.” This law declared that all runaway slaves were, upon capture, to be returned to their masters, and that any person aiding a runaway by providing food or shelter was subject to six months’ imprisonment and a $1,000 fine.

“This man made a great impression upon Stowe and her family,” Ashton says. “He was, as Stowe wrote in a letter to her sister, ‘a genuine article from the Ole Carling State.’”

While it is tempting to speculate about what the fugitive might have told Stowe on the one night that he spent under her roof, we can never ultimately know, Ashton says, adding that the historical impact of the incident stemmed from in its “domestic presence.”

“Stowe, like her husband, had long been an outspoken abolitionist, but taking this man into her house upped the stakes considerably,” Ashton says. “A man fleeing for his life was not an abstraction or an inspiration but someone who brought the stark reality of slavery into her living room. In meeting him, the corridor opened between Stowe’s intellect and her heart, and in talking with him—she was a devout Christian—she very likely would have also felt the hand of divine providence at work.”

A few months later, in early March 1851, Stowe was sitting in the family’s church pew in the First Parish Church in Brunswick when she had a vision of a man being whipped to death, a vision that she said compelled her to write Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Her novel became a best-selling book of the nineteenth century, second only to the Bible, and significantly helped energize the most consequential social revolution in American history.

“This vision drew upon a lifetime of Stowe’s impressions, research, knowledge, and experiences. Adding this man to that assortment of influences is important, because the fact that he was ‘the genuine article,’ and the fact that he was sent to her for protection in a strange town, may have been part of the final push toward the writing of her great novel,” Ashton says.

So who was this influential man?

Harriet Beecher Stowe never named this fugitive who was fleeing to Canada and, Ashton explains, Stowe had good reasons to not disclose his identity.

“It’s entirely possible that she didn’t know his name,” says Ashton, “because the Underground Railroad made a point of anonymity. But even if she did, to write or speak in specifics about the night he stayed with the Stowes would have been an admission that she violated the Fugitive Slave Act, and she might have suffered severe consequences.”

It would be another twelve years before the man’s identity was revealed—by the man himself. After a few years in the city of Saint John, John Andrew Jackson went overseas to England on the abolitionist lecture circuit and, while there, wrote and published a complex and powerful memoir of his time in bondage, The Experience of a Slave in South Carolina (1862). In this book he mentions Stowe by name and recounts the night he spent in her house:

Just as I was beginning to be settled at Salem [Massachusetts], that most atrocious of all laws, the Fugitive Slave Law, was passed, and I was compelled to flee in disguise from a comfortable home, a comfortable situation, and good wages, to take refuge in Canada. I may mention that during my flight from Salem to Canada, I met with a very sincere friend and helper, who gave me a refuge during the night, and set me on my way. Her name was Mrs. Beecher Stowe. She took me in and fed me, and gave me some clothes and five dollars. She also inspected my back, which is covered with scars which I shall carry with me to the grave. She listened with great interest to my story, and sympathized with me when I told her how long I had been parted from my wife Louisa and my daughter Jenny, perhaps for ever.

Although there has never been a strong reason to doubt Jackson’s claim that Stowe hid him overnight, some scholars of this historical period have been frustrated that it remained unverifiable. Important, too, is the timing of his overnight stay at the Stowe house. Was Jackson the trigger Stowe needed to put pen to paper and begin her history-making novel?

Literary detective work

Three years ago Ashton started an investigation that she hoped would lead to a fuller understanding of the night in question. She had already edited Jackson’s memoir for her book, I Belong to South Carolina: South Carolina Slave Narratives (see A Slave’s Life), and she wrote a further study of Jackson for her second book, published last February, which focuses on the South Carolina roots of African American thought. Still troubled by what seemed to be an incomplete sense of his life and of who he was, Ashton realized that the complexities of Jackson’s life might merit a full biography.

“As I started working through his life story, using as my primary document, of course, his eighteen-sixty-two memoir, I suddenly realized that the passage where he talks about Stowe hiding him was quite early—immediately after the Fugitive Slave Act of eighteen-fifty,” Ashton says. She tried to trace any connection between Stowe and Jackson, but Ashton found no particular mention of Jackson in any of the Stowe biographies and papers.

“I reached out then to colleagues and scholars around the country who had expertise in Stowe, and one suggested that the research staff at the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center in Hartford, Connecticut, might have an idea about overlooked sources. I contacted a reference librarian there who had never heard of Jackson but did direct me to one of Stowe’s little-known letters held at Yale University, in which she mentions hiding an unnamed fugitive slave in November or December of eighteen-fifty.” Ashton found this letter, on microfilm, and was thrilled to read Stowe’s account of a fugitive she hid, a fugitive who seemed to match what is known about John Andrew Jackson.

“Even with her husband almost certainly away— as well as her teenage twin girls, who were then visiting relatives—Stowe took the unnamed fugitive in and marveled at how well her three young children [Henry, age 12, Frederick, 10, and Georgiana, 7] interacted with the charismatic man,” Ashton says. She reads from Stowe’s letter:

Now our beds were all full & before this law passed I might have tried to send him somewhere else. As it was all hands in the house united in making him up a bed in our waste room & Henry & Freddy & Georgy seemed to think they could not do too much for him—There hasn’t any body in our house got waited on so abundantly & willingly for ever so long—these negroes posses some mysterious power of pleasing children for they hung around him & seemed never tired of hearing him talk & sing. He was a genuine article from the ‘Ole Carling State.

When she came across this letter, Ashton realized that she had two incredible documents that told a remarkable story.

“Not only had I almost certainly verified Jackson’s story, I had also provided information about a historical incident which surely informed, if not inspired, Stowe’s composition of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Also, in terms of verifying an actual event on the Underground Railway, this was tremendous too, since there are very few accounts of the railway that are documented from two perspectives—that of the freedom seeker and that of the contact who helped him along the way.”

The letter that opened doors

The night he spent in the Stowe house was not to be the only contact Jackson ever had with Stowe. Having learned to read and write after settling into Saint John, Jackson surely read Uncle Tom’s Cabin after its publication and, says Ashton, had to be surprised and impressed.

“I can imagine him saying to himself, ‘Wow, that’s the lady who hid me in Maine!’” Ashton says, laughing. “It was the bestselling novel in the world—he couldn’t have missed it by then.”

After a few years in Saint John, Jackson decided to go to England to speak on an abolitionist lecture circuit, recounting his experiences as a slave in the American South. He knew that a letter of introduction from Stowe would greatly increase his chances of doing this successfully, that it would be a form of currency, so he got a letter from her. Did he visit Stowe a second time to get her endorsement?

“Saint John isn’t all that far from Brunswick, so geographically it wouldn’t have been all that difficult for Jackson to come and see her, but because of the Fugitive Slave Act this would have been extremely risky for him,” Ashton says. “So this was much more likely just a letter exchange or was obtained through the help of sympathetic intermediaries.”

From 1856 until the end of the Civil War, Jackson lectured at churches and for social organizations in England and Scotland, and in 1862 published his book, The Experience of a Slave in South Carolina. After the Civil War, he settled in Massachusetts, shuttling back and forth to South Carolina and making a living for the rest of his life as a teacher and lecturer.

John Andrew Jackson, author

When Ashton’s discovery was widely publicized by the Associated Press—with considerable help, she says, from the media office at Clemson—Ashton got dozens of emails from Stowe scholars and others excited about this new perspec-tive that had been added to the writing of Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

These responses have been focused almost entirely on Stowe.

“The truth is,” Ashton says, “Harriet Beecher Stowe doesn’t interest me that much. Lots of scholars are out there to tell her rich and complex story. More compelling to me is that Jackson, who came from nothing, a field hand degraded and abused brutally, and not even literate at the time he was sheltered by Stowe, claimed his life by his daring act of ‘self-theft,’ as it was sometimes called, by running away. What’s more important to me is, how does somebody like Jackson come to believe his life story is worth telling, worth writing about? How did that encounter help lead him to believe that his testimony on paper mattered?”

Then Ashton brings this question home. “How do we enable people to believe their truth, their expression with words, is important and valuable? That’s our challenge today in South Carolina—how do we get students and others to believe that their stories can change the world?”

Susanna Ashton is an associate professor of English in the College of Architecture, Arts, and Humanities. Jeff Worley is a freelance writer and poet who lives in Lexington, Kentucky.