a slave’s life

Jeff Worley

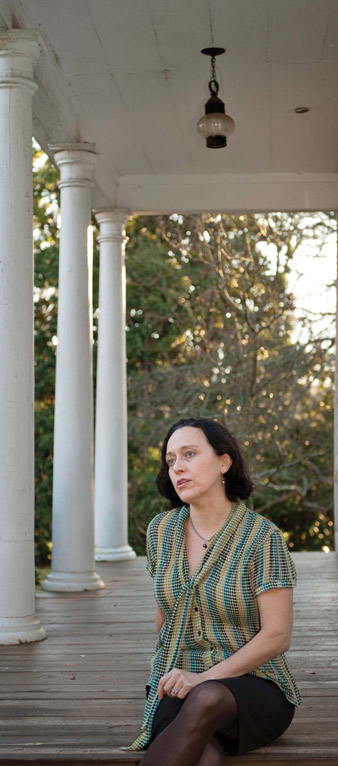

Susanna Ashton and her students gather stories that changed the world.

You got whipped for not working fast enough. You got whipped for not admitting to a minor theft you didn’t commit. You got whipped for praying, for not obeying quickly enough, for taking a muskmelon to keep from starving. And sometimes you got whipped just for the pure sadistic hell of it.

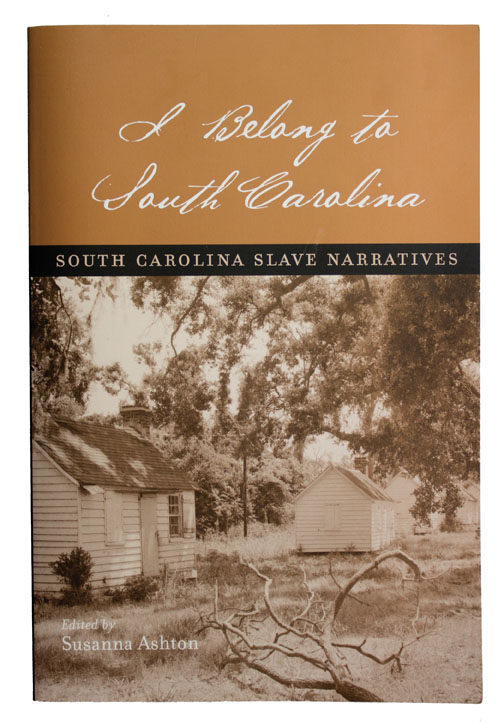

The brutal treatment of slaves—men, women and children—on South Carolina plantations for nearly a century is a tragic, recurring theme in Susanna Ashton’s recently published, award-winning book titled I Belong to South Carolina: South Carolina Slave Narratives, published by the University of South Carolina Press.

“One of the most common defenses of slavery from Southern intellectuals and plantation owners was how well taken care of slaves were,” says Ashton, associate professor of English. “‘Why would we badly hurt or kill our slaves? It’s not in our self-interest to do that. Besides, they’re part of our family and community after all.’”

This patriarchal defense of slavery seems logical, Ashton admits, but the evidence deeply contradicts these claims. “In reading through hundreds of slave narratives, you find case after case of horrific violence,” she says.

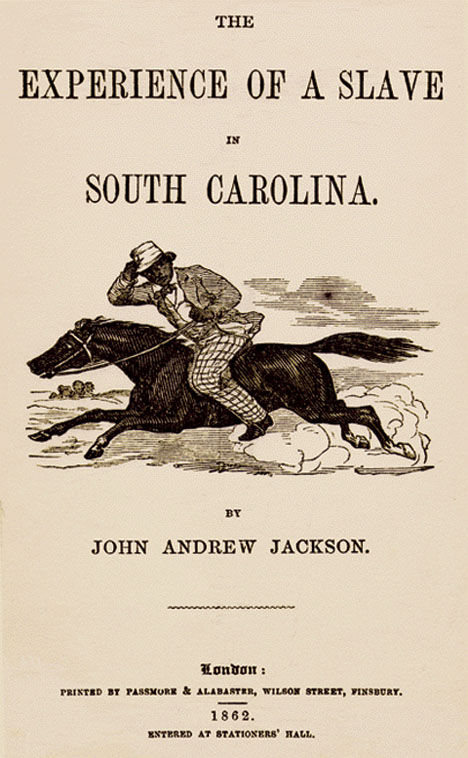

Ashton explains that the book’s title comes from one of the narratives included, “The Experience of a Slave in South Carolina” (1862) by John Andrew Jackson. After escaping from a Sumter, South Carolina, plantation in 1846, Jackson made his way to the docks of Charleston, where he lurked around the wharves, seeking a northbound boat. Suspicious workers confronted the black man, demanding to know, “Who do you belong to?”

Aware that he could not persuasively identify himself as either a freeman or a Charleston slave, Jackson dodged the question by replying simply, “I belong to South Carolina.” As Jackson later explained in his narrative, “It was none of their business whom I belonged to; I was trying to belong to myself.”

Although the seven narratives in Ashton’s book focus on individual experiences of endurance and escape, each account sought to make the extraordinary suffering of slavery both a personal and a collective horror, Ashton emphasizes.

“The writers were very aware they were also speaking for the many others who couldn’t tell their stories, couldn’t write, perhaps, so each narrative is also a communal gesture.”

South Carolina’s slant on slavery

Ashton came to this project in an oblique way.

“I moved from Iowa to South Carolina fourteen years ago and immediately loved it here, but could not get a handle on the place. People were very kind and generous, and also forward-thinking, but it seemed to me there were some things that just weren’t discussed.” She found it interesting, for example, that Clemson University founder Thomas Green Clemson often came up in personal and academic conversation, but not John C. Calhoun.

“I found this odd because, after all, the campus is on John C. Calhoun’s former plantation, and Calhoun was one of the biggest proponents of slavery in American history.”

Ashton is quick to point out that she is a literary scholar, not an American historian, but in part to better understand her new home she started teaching courses that dealt with slavery or, rather, how slavery had been represented in American culture, as well as publishing articles about slavery. This interest led her to do research at the University of North Carolina, where an extensive collection of slave narratives had been compiled.

“When reading through this collection, it occurred to me that quite a lot is known about slavery in our border states—North Carolina, for example, and stories from Maryland such as Frederick Douglass’ escape—but relatively little can be found about slavery in South Carolina. This is when I started thinking about doing a book so there would be a more complete historical and literary record.”

She adds that the culture of slavery in South Carolina is historically distinct from the cultures of slavery elsewhere in the American colonies and, later, in the American states. South Carolina’s semitropical climate and historic ties to the British West Indies created a society in which immensely profitable large-scale agriculture demanded a huge labor force—large teams of slaves—working on plantations to raise indigo, rice, or cotton as opposed to the small-scale farm crops that would demand fewer slaves.

To deal with the daunting scope of a project that would demand reading through several hundred slave narratives to identify those which focused on South Carolina, Ashton tapped into Clemson’s Creative Inquiry program, in which team-based scholarly investigations by undergraduates are led by a faculty mentor. This time it resulted in the publication of scholarly articles or a book.

“I interviewed a team of students for this project, and got them to commit,” Ashton explains. “And this year-long project was an intense commitment—we met twice a week on campus for nine months, and they read through hundreds of narratives in collections at UNC and the University of Virginia.” Ashton coedited, with a different student researcher, each narrative included in the book.

Fueling the abolitionist cause

Ashton admits that some of the events depicted in this collection are a bit tough to get through. I Belong to South Carolina is not a beach read.

“The two abolitionist narratives—one by John Andrew Jackson and the other written anonymously—are probably the hardest to read since they are such stark testimonials of violence and torture,” Ashton says.

Jackson begins his narrative with several instances of harsh treatment he received and witnessed during his time as a slave, including the role of women in the horrors of slavery. He says of the slave owner’s wife, “The sight which most delighted her eyes was to see a slave whipped,” and one of her daughters grew up to murder Jackson’s sister by having her whipped to death.

Jackson begins his narrative with several instances of harsh treatment he received and witnessed during his time as a slave, including the role of women in the horrors of slavery. He says of the slave owner’s wife, “The sight which most delighted her eyes was to see a slave whipped,” and one of her daughters grew up to murder Jackson’s sister by having her whipped to death.

“Recollections of a Runaway Slave,” written and published anonymously in 1838, is a relentlessly specific testimonial to the violence of slave practices and to the ways in which plantation culture enabled such violence. The narrator sets the tone early on in his narrative, recounting being whipped as a child. The whipping cut through his skin, but, the young man writes, “They did not call it skin, but ‘hide.’ They say, ‘a nigger hasn’t got any skin.’” In a later passage he describes in blunt and calm terms being forced to whip a young woman and rub salt into her wounds.

Jackson’s narrative was first published as an anti-slavery pamphlet by a group in Maine and then picked up by the Emancipator, a Boston-based abolitionist publication, Ashton explains. “‘Recollections’ was also an extremely important record for the abolitionist cause because it represents a specific turn in the reception of slave narratives of the 1830s,” Ashton explains. “The text was produced and published in the epicenter of controversies over the accuracy and value of slave narratives.” This story was published, in part, in the Advocate of Freedom and in full in the Emancipator.

“These accounts were published during abolitionist times to generate emotion,” says Ashton, “to shock people into action, to do nothing less than change the world—and they did.”

A choice book

In January 2011, Ashton received a letter that she says “definitely made my day.”

The letter, from Choice magazine, informed her that I Belong to South Carolina had been selected as a Choice Outstanding Academic Title for 2010. Choice is published by the American Library Association and is considered a trusted source of news about academic books by librarians and scholars nationwide. Only ten percent of the approximately 7,000 works submitted to the magazine each year are selected as Outstanding Academic Titles.

“Capturing with fidelity the texture of life for enslaved South Carolinians has challenged even the most thoughtful scholars of slavery,” says Mark Smith, editor of Stono: Documenting and Interpreting a Southern Slave Revolt. “I Belong to South Carolina is a well-edited collection of rare and under-studied slave narratives, a powerful retelling of the slave experience and a window into the complex cultural and social topography of one of America’s most robust slave societies.”

Susanna Ashton is associate professor of English in the College of Architecture, Arts, and Humanities. See the Susanna Ashton interview at C-SPAN, and if you want to see other work being done in Clemson about South Carolina’s local history, please watch Soapstone Cemetery.