Struggling toward the Promised Land

Jeff Worley

How the Exodus narrative helped sustain generations of blacks seeking freedom and equality.

Rhondda Thomas knows the power of a good story. One story in particular, the Exodus narrative, captivated her when she was a girl in Sunday school making her first voyage through the Bible. As she grew into her teens, went to college and then to graduate school, Exodus began to take center stage in her academic life.

“When I started my graduate studies and did research on the Exodus story, I found that scholars had taken a very limited view of the story’s potential and the power of this narrative through many years to drive and nourish blacks in their quest for freedom,” Thomas says. Her hunch was that many black writers, especially during the nineteenth century, had mined Exodus for its allegorical power.

It turned out Thomas was right.

“I did a search on Exodus stories, and I found them everywhere,” she says. “And in the sermons, letters, books and other written materials I researched, I was taken by the multiple ways this narrative was sustained as a way to express the strong desire for freedom.”

Thomas continued her search-and-find mission through graduate school with an eye toward writing and publishing a book. Claiming Exodus: a Cultural History of Afro-Atlantic Identity, 1774-1903, was published early this year by Baylor University Press.

“Exodus was of course an oral tradition before Moses wrote it down, and sermons are also part of the oral tradition, but in America the print culture is such an integral part of our identity, I wanted to focus on the written, literary convention in this country,” Thomas says. “So even the sermons I discuss in the book were written down and widely circulated.”

In Claiming Exodus, Thomas mentions several dozen black writers who used the Exodus myth to further blacks’ struggle for freedom, but she says there are three who played especially important roles in the drama of emancipation and self-realization: Phillis Wheatley, Absalom Jones, and W.E.B. Du Bois.

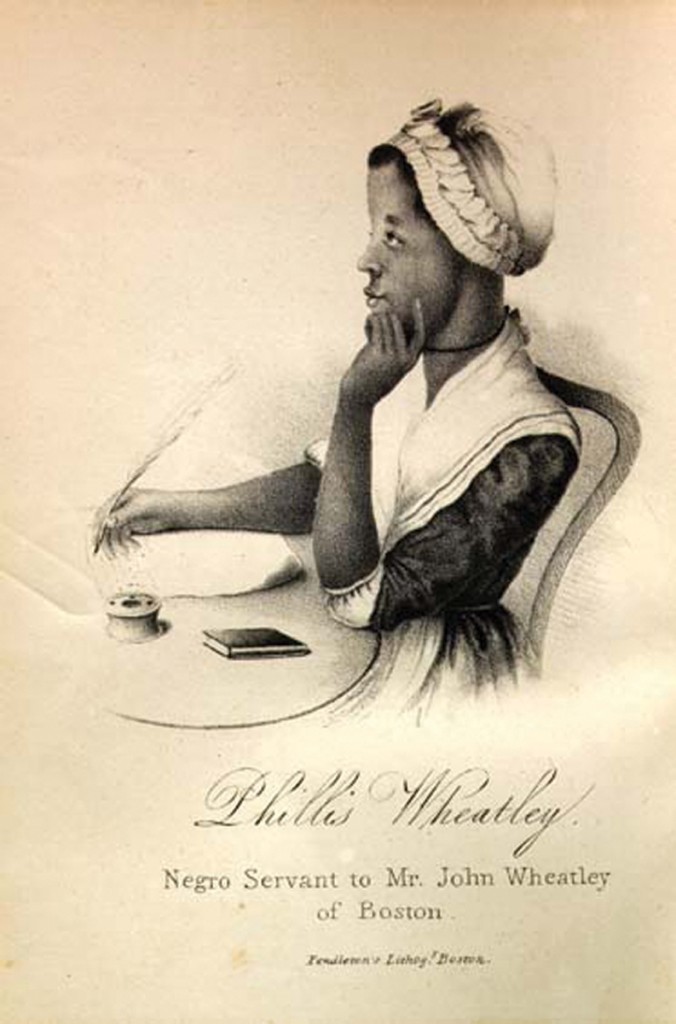

Phillis Wheatley: Include American slaves in the revolution.

Thomas found that the first person in America of African descent to use the Exodus story was also the youngest—Phillis Wheatley. She was eight years old when she was brought to Boston on a slave ship in 1761, and John Wheatley, a prosperous Boston merchant, purchased her as a personal slave and companion for his wife. Phillis received a solid education and, at age fourteen, began to publish her poetry and letters in Boston newspapers. In 1773, John Wheatley emancipated her.

“Being freed from her master may have given the celebrated Wheatley the confidence to evoke Exodus in penning her strong abolitionist statement in ‘Letter to Reverend Samson Occum,’ published on the eve of the American Revolution,” Thomas says. “In her letter Wheatley draws on the rhetoric of the Exodus narrative and Enlightenment theory to elevate Africans from abject bondsmen to rational, spiritual human beings. In doing so, she shifts the objective of the Revolution from the colonists’ emancipation to the physical, religious, and political liberation of all Americans—including Africans.” Thomas adds that in the closing of her letter, Wheatley invokes biblical precedence, suggesting that Africans’ pleas for liberty are equivalent to ancient Israelites’ prayers for deliverance from Egyptian slavery.

“Basically what Wheatley does in this letter is point out the absurdity of the colonists using the Exodus narrative in their demand for liberty while still believing they should enslave Africans,” Thomas says. “This former slave girl was sharply questioning their sense of reason.

“Wheatley was likely the most prominent African American of her time to publicly demand the abolition of slavery during the American Revolution, which effectively complicated the debates regarding race, citizenship, and freedom.”

Absalom Jones: gradual emancipation and community building

More than thirty years later, another strong voice in the struggle for liberty extended the Exodus myth: the Reverend Absalom Jones of St. Thomas African Episcopal Church in Philadelphia. On New Year’s Day, 1808, Jones preached “A Thanksgiving Sermon” on the occasion of a new law, taking effect that day, that prohibited the nation’s participation in the slave trade.

“In his sermon Jones characterized American slaves as ancient Israelites whose cries had moved God to convince politicians in Congress to outlaw the slave trade,” Thomas explains. “Jones evoked the Exodus narrative to interpret this legislation as a divine sign portending the emancipation of the slaves,” Thomas continues, “transforming free black Philadelphians into activists who should now continually commemorate their victory and aggressively work for civil rights.”

Thomas adds that by the time he delivered his “Thanksgiving Sermon,” Jones was sixty-two years old, a confident, Moses-like figure in the antislavery cause.

“His sermon was published and distributed and read widely,” Thomas says, “and it helped black Philadelphians to become one of the most activist communities in the nation.”

W.E.B. Du Bois: Booker T. Washington as a potential Joshua

In Claiming Exodus, Thomas discusses a number of writers who used and extended the Exodus narrative in the struggle toward freedom through the nineteenth century’s pivotal events: the War of 1812, the great debates of 1820s, Manifest Destiny, the Civil War, and Reconstruction. Championed by black activists, various black leaders through the century came to represent Moses figures or Joshua figures (Joshua became the leader of the Israelite tribes after the death of Moses).

W.E.B. Du Bois, the first African American to earn a doctorate at Harvard and cofounder of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1909, somewhat reluctantly supported Booker T. Washington as a potential Joshua figure at the turn of the twentieth century, Thomas says, adding that the two men were not always in agreement as how best to accomplish their shared goals. “Du Bois would have wanted a leader who took a more radical approach to white Americans’ insistence on second-class citizenship for African Americans but said that to the extent Washington, the builder of the Tuskegee Institute, preached ‘thrift, patience, and industrial training’ for the masses, blacks should strive with him and glory ‘in the strength of this Joshua called of God and of man to lead the headless host,’” Thomas says, quoting her book.

With additional support from Andrew Carnegie, who singled out Washington as the ‘modern Moses,’ Washington was regularly identified by white newspapers throughout the nation at the turn of the twentieth century as the African Americans’ Moses, securing his status as race leader and affirming his more conservative strategy as the solution to the problem of the color line, Thomas concludes.

Logging in lots of library time

Thomas describes the eight years of research and scholarship that led to the publication of Claiming Exodus as emphatically not glamorous.

“There were not the online databases there are now, so to try to find these stories I spent hundreds of hours reading bound volumes and painstakingly going through microfilm, despite the fact that whirling through microfilm actually makes me nauseous.”

Thomas’s research took her from Washington D.C. (Howard University) to Atlanta (the Emory University archives) to South Carolina (the Historical Society), and to Charleston, Philadelphia, and Boston. The occasional surprising finding was one of the things that kept her going, says Thomas.

“One of my best finds—this was in the American Antiquarian Society archives in Worcester, Massachusetts—was a letter from Frederick Douglass near the end of his life to Francis Grimké, a Presbyterian Church pastor in Washington, D.C. As far as I know, no one had known of the existence of this letter, which talks about the Promised Land,” Thomas says. Grimké was an important racial activist in the early twentieth century.

Another major discovery Thomas made through her research was that the writers she investigated had a far broader concept of the “Promised Land” than she had expected.

“I grew up thinking that either the American North or Canada was the Promised Land for blacks seeking their freedom,” Thomas says, “but I discovered through my research that writers also thought of the American West, East and West Africa, and even England and France as the Promised Land. Finding a multiplicity of promised lands was an interesting surprise.”

Why is the Exodus story so powerful?

“Every major moment in American history has seen a proliferation of Exodus narratives,” Thomas says. “The story is an epic narrative chock-full of drama, suspense, and a tremendous fight between good and evil. It’s the dominant narrative used by white and black Americans over and over again to try to keep their quest for freedom and democracy going. Collectively, the Afro-Atlantic Exodus stories sustained the momentum of early civil rights efforts.”

Rhondda Thomas is an assistant professor of African-American literature in the Department of English, College of Architecture, Arts, and Humanities. Jeff Worley is a freelance writer and poet who lives in Lexington, Kentucky.

The Exodus narrative

The Book of Exodus tells how Moses leads the Israelites out of Egypt and through the wilderness to Mount Sinai, where God reveals himself and offers them a covenant: They are to keep his torah (i.e., law, instruction), and in return he will be their God and give them the land of Canaan. The Book of Numbers tells how the Israelites, led by their God, journey from Sinai towards Canaan, but when their spies report that the land is filled with giants, they refuse to go on. God condemns them to remain in the wilderness until the generation that left Egypt passes away. After thirty-eight years at the oasis of Kadesh Barnea, the next generation travels on to the borders of Canaan. The Book of Deuteronomy tells how, within sight of the Promised Land, Moses recalls their journey and gives them new laws. His death concludes the forty years of the exodus from Egypt. According to Exodus, Numbers, and Joshua, after Moses’ death Joshua became the leader of the Israelite tribes.

—source: Wikipedia