Serious science, safer food

by Anna Simon

In the fight against food-borne pathogens, nothing is off the table, not even the grocery bag.

Norovirus is no laughing matter.

Bathroom humor, however, is inevitable when 25 college students armed with swabs collect more than 5,000 samples from toilet seats, flush handles, sink faucets, and door knobs in more than 750 randomly selected restaurant restrooms across three states in search of the hardy virus in places where we eat.

In pairs, male and female, students posed as customers, ordered food, and surreptitiously visited restrooms to gather samples. Graduate student Chaoyi Tang says she checked bathrooms before eating and left her food untouched if the bathroom was nasty.

One student had just pulled on latex gloves when the restaurant manager walked into the men’s room where he was about to take samples.

Awkward.

It’s all for science, though.

Norovirus is the most common cause of food-borne disease in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The virus is persistent in the environment and easily transmitted by infected people, contaminated food or water, or contact with contaminated surfaces. Symptoms include diarrhea, stomach pain, nausea and vomiting, with possible fever, headache, and body aches.

Remember when multiple Norovirus outbreaks sickened hundreds of passengers on cruise ships early this year? Cruise ships are not the most common setting for Norovirus outbreaks, says Angela Fraser, associate professor in Food, Nutrition, and Packaging Sciences and principal investigator for Clemson’s $2.5 million piece of the U.S. Department of Agriculture project, NoroCORE, to reduce Norovirus outbreaks.

About 60 percent of outbreaks occur in health-care settings, particularly nursing homes, where patients are at higher risk because they are in close contact and in poor health. Day-care centers, where toddlers play on carpeted floors, also are common breeding grounds, Fraser says.

Cases of Norovirus infection attributed to food sicken nearly 5.5 million people in the United States annually and lead to more than 14,600 hospitalizations and 149 deaths. A whopping 11 percent of people who get sick with a Norovirus infection die, according to the CDC.

Fraser leads the outreach portion of the NoroCORE project. She and her team, who are working to improve the quality of training and information about noroviruses, were surprised at the lack of Norovirus knowledge among food-safety and public-health professionals “on the front line helping others prevent and control Norovirus,” Fraser says.

“Information about noroviruses is readily available,” she adds. “What we don’t know is how clear and practical it is.”

Food microbiology professor Xiuping Jiang heads the laboratory portion of the NoroCORE project.

The thousands of swabs collected from bathrooms are stored in freezers in Jiang’s lab. She and her graduate students extract nucleic acid from the samples, purify the RNA, amplify the target genetic sequences, and use fluorescent dyes to test for Norovirus.

Another project in Jiang’s lab determines the efficacy of sanitizers used on surfaces such as carpets, upholstered chairs, and curtains. Much work already has been done on sanitizers used on hard surfaces, but information is lacking about sanitizers for carpets and other soft surfaces, which require more highly concentrated disinfecting solutions because of their fibrous structure, Jiang says.

Graduate student Thomas Yeargin is looking for ways to extract Norovirus, using surrogates of the virus, from carpet and other soft surfaces. “Case studies are implicating carpeting in a lot of Norovirus outbreaks,” Yeargin says. “Norovirus is more resistant to disinfectants and sanitizers than some other viruses and bacteria.”

The scientific community has become more interested in soft surfaces and development of textiles and draperies with antimicrobial properties, says Yeargin, who will be Clemson’s first NoroCORE graduate and will start a paid internship with a national manufacturer of cleaning products as a visiting scientist studying surface sanitation.

This type of in-depth study of a virus is an emerging science, because Norovirus cannot be cultured in the lab, Jiang says. Researchers typically use surrogate viruses to simulate the behavior, she says. Researchers want to learn more about how long viruses persist, how they spread, how to control and kill them, and how to know when a virus is completely dead and no longer infectious, she says.

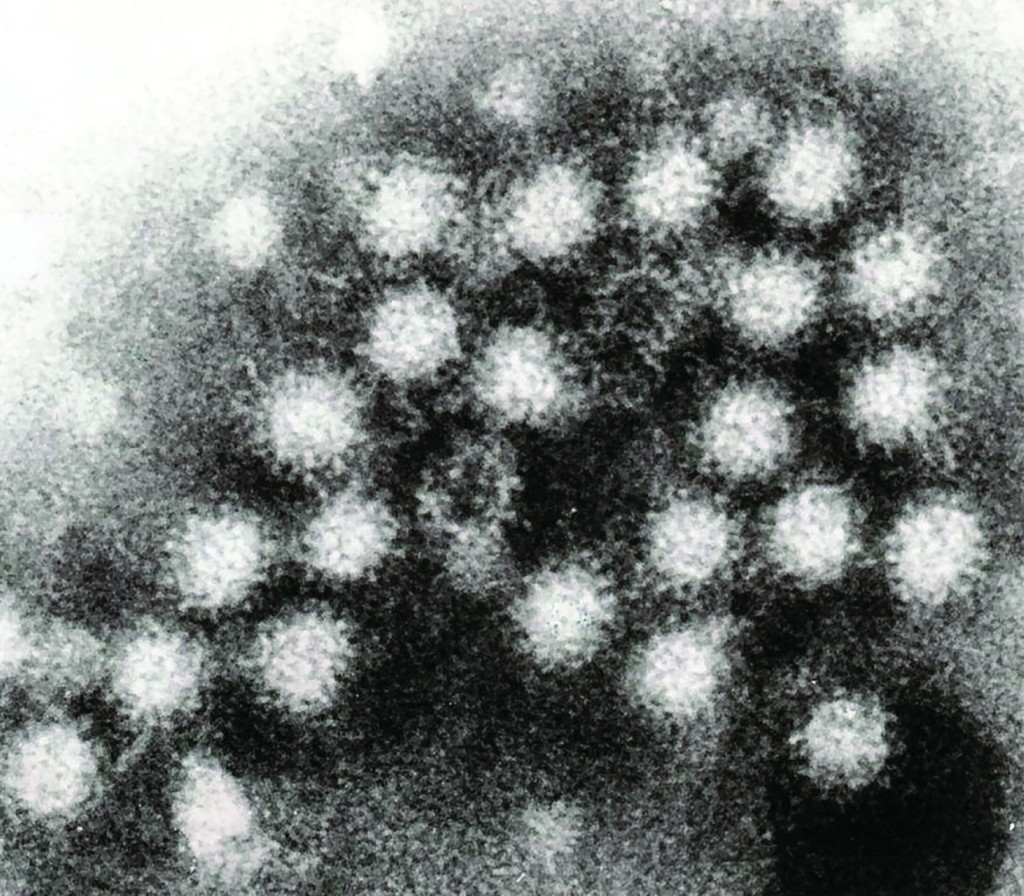

Micrograph of Norovirus, a common cause of food-borne illness. Image courtesy of Graham Colm.

Micrograph of Norovirus, a common cause of food-borne illness. Image courtesy of Graham Colm.Lettuce eat safely

While centrifuges in Jiang’s third-floor lab in Clemson’s new life sciences building spin nucleic acid from swabs to study Norovirus, another area of her research focuses on produce safety.

Her targets include Salmonella, E. coli, and other bacterial pathogens that can taint fresh produce. One of Jiang’s larger grants was spurred by what the industry calls “the two thousand and six spinach crisis” in California that caused 205 confirmed illnesses and three deaths.

Of four basic food categories listed by the CDC, produce is the culprit in 46 percent of food-borne illnesses and 23 percent of the resulting deaths. Meat and poultry are next, accounting for 22 percent of food-borne illness and 29 percent of deaths.

Food-borne disease sickens roughly one in six Americans, or 48 million people, per year; 128,000 of them are hospitalized, and 3,000 die, according to CDC estimates. The agency ranks Salmonella second, behind Norovirus, as a contributor to food-borne illnesses, and first in hospitalizations and deaths.

Salmonella, Jiang says, is very hardy and persistent in the environment. It’s been found in fertilizers made from animal waste—fertilizers typically used to grow fresh produce, Jiang says.

Even though producers compost animal waste to generate high temperatures that deactivate pathogens, science-backed guidelines are lacking. Jiang leads several studies, supported by the Fresh Express Produce Safety Initiative, the Center for Produce Safety at the University of California, and the USDA, to determine the temperature needed and how long it must be maintained to do the job, along with other factors in composting. The findings will be used to establish guidelines for manufacturing organic fertilizer that will be safer for growing fresh produce.

Another area of Jiang’s research examines rendered animal byproducts in order to reduce Salmonella in animal feeds. When an animal is slaughtered, 42 percent of the animal, including the bones and intestinal contents, goes to the rendering industry, Jiang says. Ultimately, the research could help prevent Salmonella from being carried up through the food chain to our dinner tables, as well as protecting our family pets from food-borne illness.

Paper or plastic?

Paper or plastic?The meat of the matter

All too often, contamination finds its way into packaged meat. Kay Cooksey, with expertise in food and packaging science, is developing antimicrobial materials to protect sliced deli meats from contamination. Pathogen pathways in a deli environment can include meat slicers, improper use of gloves, and countertops where food is prepared, Cooksey says. It takes eight hours to disassemble and clean a meat slicer, and a person must be specially trained to do it, Cooksey says.

Cooksey and her doctoral students have designed layers of a material containing an antimicrobial agent to place between meat slices to reduce growth of pathogens (see Wrapping up food safety). A private company is interested in the potential product, and a patent application has been filed, Cooksey says.

The process still must be refined before it can be commercialized for large-scale, high-speed manufacturing. For example, a step for drying the product, which happens overnight in the lab, would have to occur almost instantly in a manufacturing plant, Cooksey says.

Cooksey’s research is developing other antimicrobial safeguards, as well. One is a countertop that contains durable, long-lasting antimicrobial agents. Another is an antimicrobial material to protect sliced tomatoes and bean sprouts used in the restaurant industry. The material slowly releases a vapor that prevents spoilage during shipment to restaurants without affecting the taste.

Your habits with grocery bags can affect not only the environment but the safety of your food.

Your habits with grocery bags can affect not only the environment but the safety of your food.What’s on the menu?

Meanwhile, two of Cooksey’s colleagues, Julie Northcutt and Paul Dawson, have taken what might be called a hands-off approach to food safety. Northcutt and Dawson have studied, for example, restaurant menus, and the results have convinced Northcutt to wash her hands each time she touches one.

The menu study is one of a series of quirky popular science projects Dawson places before undergraduates as Creative Inquiry studies to whet their appetite for research. In the menu study, students discovered that 10 to 11 percent of bacteria on people’s hands were transferred to menus during handling. Other such projects have debunked the three-second rule on dropped food, have found bacteria spread by blowing out candles on a cake, and have documented the risky behaviors of double dipping, shared drinks, and shared dishes of food.

Unexpected results of a Creative Inquiry project on washing fruits and vegetables found that successive rinses, after the first, failed to lessen bacteria concentration in the rinse water, particularly for vegetables such as lettuce and broccoli compared to smoother-surfaced apples and grapes, Dawson says. Results varied widely: Between 20 and 90 percent of the bacteria removed in five rinses of common fruits and vegetables were removed in the first rinse.

Beer pong was the subject of another Creative Inquiry investigation. On a home football weekend, Dawson’s students looked for tailgaters and partiers playing a game that involves tossing a ping pong ball into drinks. Students traded new ping pong balls for used ones to study and found millions of bacteria on them, especially on the balls used in games played outdoors. The highest level of bacteria found on ping pong balls was 2.9 million and the least was 180, and the alcohol in the drinks didn’t kill the germs. Dawson likens the game to Russian roulette with one’s health.

In the lab, Dawson and Northcutt collaborate with Furman University chemists on a quick and thorough way to determine cleanliness in commercial food-processing facilities. They use microscopic substances called liposomes that can be designed to change color in contact with bacteria. The idea is to be able to swab a surface, add liposomes, and immediately know if a surface is microscopically clean, Northcutt says.

The concept is much like the pills dentists have children chew that color areas missed in brushing their teeth, Northcutt says. The process, which is close to commercialization, would help protect our food supply, help the food industry comply with regulations, help inspectors spot issues, and enable line workers to make immediate decisions rather than wait on lab results, Northcutt says.

Or bring your tote?

Or bring your tote?Paper or plastic?

Even when our food is free of contamination at the point of purchase, we can foul up the works when we bag it to take home. Reusable, nonwoven fabric bags, the type typically sold at supermarkets for 99 cents, must be washed frequently to prevent cross-contamination from one shopping trip to the next, Cooksey says. The problem: Only 15 percent of people who use reusable fabric bags wash them often, and 28 percent of people who use them never wash them, according to a study by Edelman Berland, a market research firm, Cooksey says.

Clemson researchers Bob Kimmel, director of Clemson’s Center for Flexible Packaging, and Cooksey, together with Allison Littman, a Clemson alumna, conducted their own study to evaluate the environmental impact of four common types of grocery shopping bags. At a time when cities and counties of all sizes across the nation are considering legislation to deal with perceived plastic bag litter, the researchers wanted a scientific answer to the checkout-line question: paper, plastic, or reusable?

“There are so many misconceptions,” says Kimmel, principal investigator for the study. “The popular press picks up unconfirmed data and environmental groups latch onto it. There are always preconceived notions on what is good and what is bad. One reason for the study is to separate fact from fiction.”

Kimmel, Cooksey, and their students examined the cradle-to-grave impact of four types of bags: brown paper grocery bags, lightweight plastic grocery bags, reusable fabric bags, and heavyweight plastic retail-store bags.

They considered twelve environmental impacts including carbon footprint, energy use, and chemical impacts on soil, water, and air. They looked at reuse, recycling, and recycled material recaptured in making new bags. Some bags hold more than others, so an undergraduate Creative Inquiry group analyzed how many of each type of bag would be needed on an average shopping trip for a family of four.

Of the two types of bags intended for one-time use as grocery bags, paper and lightweight plastic, plastic was a clear winner, largely due to the manufacturing and waste recovery processes. Although paper bags are made from trees, a renewable resource, and can be recycled at curbside, the water- and energy-intensive processes of turning logs into cellulose fibers then paper tip the scales in favor of the lightweight plastic bags. Although lightweight plastic bags can’t be recycled at curbside because they foul up the sorting machinery, about 93 percent of U.S. residents have access to recycling locations at many supermarkets and other retail points, Kimmel says. In addition, lightweight plastic bag manufacturers can use recycled bags to make new ones.

The researchers found that when compared on a one-time use basis, paper bags are on average four to seven times more detrimental to the environment, Kimmel says.

The analysis is trickier between lightweight plastic and the two types of reusable bags and depends in part on how many times the reusable bags are reused and whether the lightweight bags are put to secondary uses, such as trash-can liners or to carry other items, Kimmel says.

A separate survey by Edelman Berland found that while the average number of reuses for the heavy plastic bags is 3.1 shopping trips, 6 to 9 trips would be needed to make them more environmentally friendly than the lightweight plastics, Kimmel says.

Nonwoven fabric bags must be used at least 20 times to be equivalent in their average environmental impact to lightweight plastic bags, Kimmel says. This number increases to 33.5 times if secondary uses of lightweight plastic bags are taken into account.

Reusables get dirty

The national survey showed that the average person uses his or her fabric reusable bags for 14.6 shopping trips, Kimmel says, and only 20 percent of people who use the nonwoven fabric bags use them more than 44 times. Right now, about 6 percent of the nation’s population lives in areas covered by some kind of plastic bag legislation, which is heavily concentrated on the West Coast, the Northeast, and in Texas, he says. Average use is 17.3 shopping trips in legislated areas and 13.9 trips in nonlegislated areas. “So people in legislated areas still aren’t using their bags that many more times than the average and still not enough times to make their average environmental impact less than that of the lightweight plastic bags,” Kimmel says.

“Reusable bags are great if you reuse them enough times and keep them clean,” Kimmel says. “The majority of people today aren’t doing that.” Typical legislation calls for stores to sell the customer a paper bag if they don’t bring a bag with them, “which is the wrong choice for the environment,” Kimmel says.

Kimmel and Cooksey recommend, based on their study, that “consumers should be given a choice between reusable bags and lightweight plastic bags and that the use of paper bags should be discouraged.”

“Much more attention,” they write, “should be focused on educating consumers to make an informed choice of which bags to use by providing them facts—facts about reusable bag use, facts about proper recycling or disposal of lightweight plastic bags, facts about the potential environmental impacts of their choices—based on sound scientific evidence.”

Angela Fraser is an associate professor in Food, Nutrition, and Packaging Sciences and is principal investigator for Clemson’s $2.5 million portion of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s $25 million NoroCORE project. Xiuping Jiang is a professor in the Department of Biological Sciences. Kay Cooksey is the Cryovac Endowed Chair, and Julie Northcutt and Paul Dawson are professors in the Department of Food, Nutrition, and Packaging Sciences. Bob Kimmel is an associate professor of packaging science and the director of Clemson’s Center for Flexible Packaging. All are in the College of Agriculture, Forestry, and Life Sciences. Anna Simon is a freelance writer based near Pendleton, South Carolina.