art for the fearless

On this crisp Sunday morning, Shannon Robert and I sit on the removable step of the marbled dais while undergraduate Cassey Lanier fetches the paint. Today Robert will teach Lanier how to repaint a damaged wall.

The repairs I’m about to witness today will have to be done every morning before each show over the next week, and this is only the tail end of the set designer’s work.

When Robert met first with French, she’d read the play but she went into the meeting knowing little more than what the seating arrangement would be. “I always get ideas when I read a script,” Robert says. Although she had researched the Italian setting, “Charles Mee’s approach is not realistic. I would call it magical realism meets poetry meets… I don’t even know. It defies definition. To approach the play realistically isn’t serving it the way it wants to be served.”

At the meeting, the team talks about what the play means to each of them. What-ifs are bandied around the room. “Because this is a collaborative art,” Robert says, “maybe your ideas change a little. It may not be exactly what you thought you were going to do in the first place.”

In the meeting, French spoke about her experiences in Italy. The photos of clotheslines got Robert thinking about this world’s form and function. Given that French wanted to use three brides and three grooms to represent the fifty (of each) mentioned in the play, Robert thought: These girls talk about hanging themselves. So, fifty hanging dresses—they aren’t the brides, not literally. What if this could be the canvas for the lights to play on?

Calls went out for bridal gowns. Emails, Facebook requests, and then Robert turned to borrowing from other theaters. For each dress, the crew arranged pickups and tagged the gown so it could be returned to the correct owner.

Once Lanier has found the paint—a beige, a black, and a white—Robert gets down on her knees next to Lanier to take a look at some of the floor-level damage to the wall. Due to the rough, “painterly” style and dim lighting during the show, the spackle won’t need to be sanded out. Lanier can paint it now.

Robert shows Lanier how to blend, how to dry brush it to get distinctive brush strokes, and how to fix mistakes. Then she hands the brush over to Lanier and sits back to supervise while Lanier gets some hands-on experience.

The floor she’s stepping on, which looks like a high-quality marble laminate, she made. Starting off, Robert “based out” the floor in white. With varieties of Italian marble in mind, she painted, taking into account rock’s geological formation. The gray tone in these tiles is natural, but Robert added pink “for a little lift.” That, and the blue tones, allude to the gendered theme of the play.

“Painting it is a very, very wet process,” Robert explains. “It’s sprays and slinging and lots of wet, and once it’s done, we seal it.”

You’d think that her job would be finished with sealing, but in reality, this floor requires continual upkeep. Typically, Robert explains, “we don’t do black, rubber-bottomed shoes if we do a light colored floor.” But in this case, the actors dressed as grooms had to wear dark dress shoes. So, after every performance, scuffs mark the floor. Cleaning them removes the seal, so the floors must be resealed afterwards.

Part altar, part boxing ring

Robert waves at the columns around us and says, “I knew I wanted to frame the set. I wanted it to have a ritual feel. Like an altar. The cake, the celebration. A boxing ring, enclosed.”

The four columns framing the set were cut down from three beams used in a previous production. The fourth column was constructed from end pieces.

“These,” Robert says, pointing up at the columns, “are top heavy, but they’re tied in with aircraft cable that’s connected all the way through. They’re basically hanging. They can move and flex a little, but they’re not going anywhere because they’re supported at the bottom too.”

The square bases, neither Corinthian nor Doric, also originate from another show.

Remaking pieces from old sets is not only practical and frugal, but also a conscious pedagogical decision on Robert’s part. She says, “We’re teaching students how to reuse, recycle, and upcycle. I am making a concerted effort not to put more material in the landfills.”

The swags of cloth draped around the columns give the stage a wedding-like feel and, as Robert explains, “The fabric is left over from our gala last year. The entire lobby of the Brooks Center was draped in fabric. It was really lovely, so I pulled some of that out.”

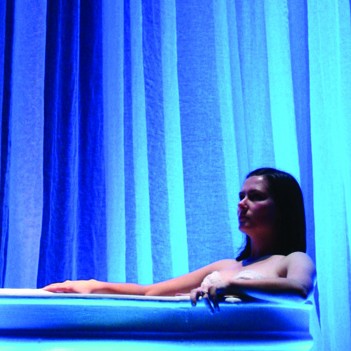

But more here around us has been upcycled. Robert taps a surface beneath the bathtub that looks like clouded glass, and says, “This lexan has been used in many shows. In fact, I think I’m going to use it for my next show. The tub was a trough.”

Robert has a “footed tub that’s quite lovely” but chose the trough because, on top of the podium, it mimics the shape of a stacked wedding cake. The cake, which is perched upon the trough near the play’s end, becomes a final piece of the puzzle that gets slotted in.

Learning their way out of a mess

The cheap scenic gauze draped around the podium at the beginning is meant to represent “a protective bridal veil” that the girls tear down. Velcro tabs hold this netting to a hanging white frame. That frame is metal, Robert says, looking upward. “They welded it and painted it white. The structure is designed to bear the load of all action in the play.” The frame lowers, so that it can be dressed, from the grid above, which according to Robert, “could hold a couple of busses.”

The technical director, Matthew Leckenbusch, has done the math. He’s figured out the load. For everything. He’s calculated the weight the swing can hold, taking into account how the 450-pound rope is expanded by the swing seat’s two-by-ten. He figured how much weight the lexan could hold.

“Every time we do anything,” Robert says, “it’s a collaborative effort.”

As we sit, Robert gives occasional instructions to the student, Lanier, to help her with technique. “Just change your pressure until you get the desired effect. Don’t worry about those spatters down there. We’re going to go back and deal with those shortly because you may get a few more as you’re going. I want you to get a ladder so that you’re comfortable, not reaching.”

As Lanier leaves to get the ladder, I ask Robert if it’s possible do this work if you’re afraid of heights. Robert gives me a long look. “Anyone who’s interested in scene painting, they have to be able to go up. That, really, in some cases can be as important as being able to paint.”

More than being willing to brave any height for painting, a set designer must be fearless. Robert explains that she likes her students to make mistakes, because then students learn how to figure their way out of the mess they’ve gotten themselves into.

But making mistakes is hard. It takes guts to look at something, know exactly how badly you might fail, and do it anyway. Some mistakes can hurt worse than a fall off a ladder.

“If they can’t problem solve, they won’t work in this field. Or, in any field,” Robert says and turns to instruct Lanier. “Feather it out. Change your pressure, so that you’re kissing the surface with the paint.”

“I’m afraid I’m going to mess it up,” Lanier says.

“I know. You got this,” Robert says. “It’s going to do exactly what you tell it to.”

That willingness to jump right in serves Robert well. She has worked on high-profile large productions in cities and says that, because people don’t know the type of work that goes into this, there can be a condescending attitude toward what she does. She says on a recent project she encountered an artist with the attitude of: “You do this theater stuff. I do real painting.” It doesn’t seem to matter to them that Robert has been educated in art and architecture, and that she’s got experience with fine art as well.

When Lanier asks Robert if the wall looks finished, Robert takes a good long look at it. She explains that Lanier has missed some spackle. Even though it’s white on white, not visible to the audience, it needs that layer of paint. If the actor hits it with a ninja star, “it could crumble out if it doesn’t have a coat of something on top of it.”

Lanier nods, a little glumly, and goes back to work.

“It’s definitely not for everyone,” Robert says. “I tell students: If this is something you can’t not do, great. If there is something else you would be happy doing, this can be… a soul killer, a soul crusher of a job. You hear no so many more times than you hear yes. You are assumed incompetent until you prove otherwise.”

As I’m making ready to leave, Robert gets on the floor next to Lanier. They’re putting down the black all-floor, a low-sheen paint. The floor around the stage needs a layer tonight, because the actors have smashed plates on it, and it’s looking a little chipped. Robert tackles the problem, in her element, right in the action, with a paintbrush in her hand.

Shannon Robert is an associate professor of theatre in the Department of Performing Arts, College of Architecture, Art, and Humanities.

From the first scan of script to the jitters of opening night, a play sweeps the faithful away on a journey of fearsome discovery.

Tony Penna bides in a liminal space, between light and darkness.