Writing Toward Freedom

by Neil Caudle

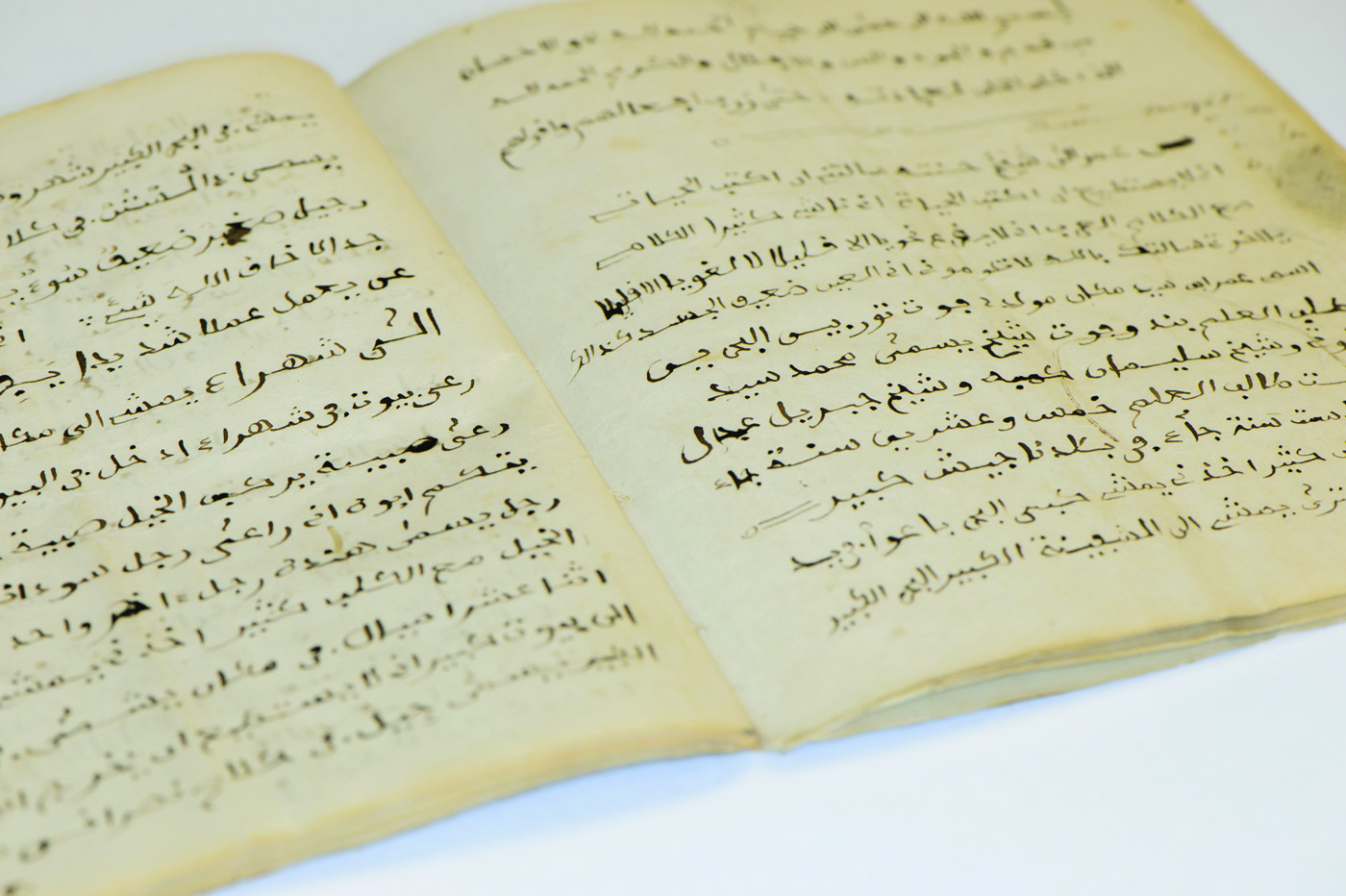

The manuscript opened to its Arabic text.

How a slave savant charmed his masters even as he denied their right to own him.

The year was 1810. People in the streets of Fayetteville, North Carolina, began spreading the word about a stranger, a black man under lock and key in the local jail. He was a slight man, perhaps forty years old, worn thin from scant rations and heavy labor—a runaway slave who had been captured in a church, where he had found shelter to pray. In his jail cell, the man had been writing—a remarkable thing in itself for a slave. He had reached into a pile of ashes, fished out the nuggets of coal, and used them to fill up the walls with odd symbols.

People who had witnessed this curious behavior claimed that the man wrote backward, right to left, in a strange kind of language none of them had ever seen. Very soon, the man was a local phenomenon, a sensation. White people stopped by to watch him and marvel. After sixteen days, having written his way into the sympathy of Fayetteville’s populace, the man walked out of his jail cell in the custody of another white owner, a man by the name of James Owen. The stranger was still a slave, but the beatings and privation he’d suffered were over. “They are good men,” he wrote later, of Owen and his brother, “for whatever they eat, I eat; and whatever they wear they give me to wear.”

The text on the jailhouse walls was in Arabic, and its author was Omar ibn Said, a Fulani Muslim tribesman of Futa Toro, modern-day Senegal. Born around 1770, he had devoted twenty-five years of his youth to religious education then worked as a teacher and trader before he was captured, in 1807, by a warring African army and sold to a slaver. His journey across the big sea, as he called it, through the Port of Charleston, into the hands of an abusive owner named Johnson, was cruel enough to crush a lesser man. But Omar survived, and so did his faith in the power of words.

Omar’s original manuscript about his life journey, The Life of Omar Ibn Said, Written by Himself (1831), now occupies a place of honor at Clemson, on loan from its owner, the collector Derrick Beard. It’s a remarkable document, not only for its historical eminence as the only autobiography written in Arabic by a slave in America but also as a mysterious and multilayered appeal on the subject of dominion: Who has the right to master other men? Only God, Omar argued, is entitled to hold such power. This was his topic and his striving—in effect, his jihad. Quoting passage after passage from the Qur’an, weaving them together with lessons from the Christian Bible, Omar was writing for his life.

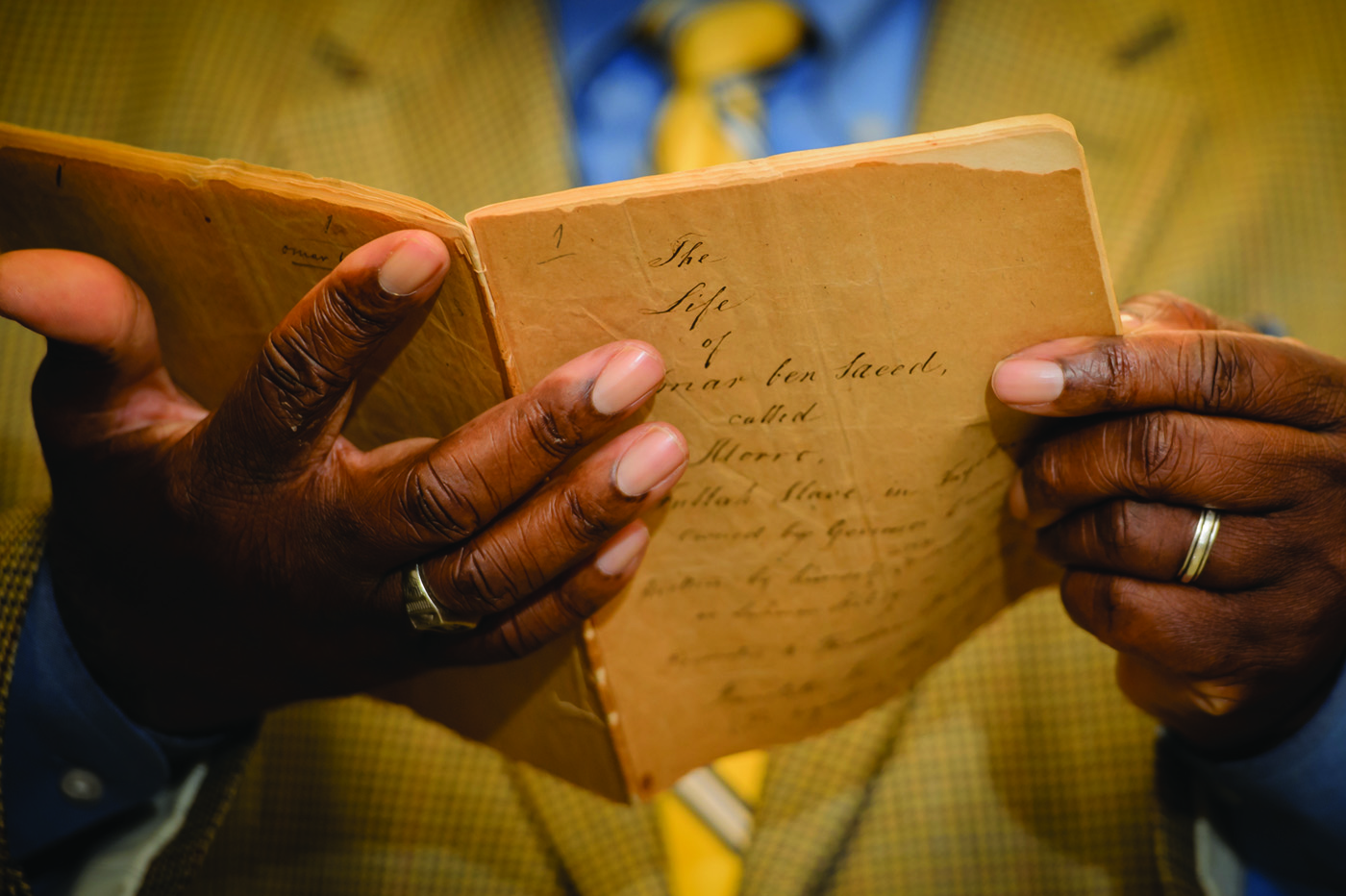

Akel Kahera with the manuscript written in Arabic by Omar ibn Said while he was enslaved near Fayetteville, North Carolina.

Akel Kahera with the manuscript written in Arabic by Omar ibn Said while he was enslaved near Fayetteville, North Carolina. A treasure rediscovered

Akel Kahera, an architect and scholar, first took an interest in Omar ibn Said when he was a Ph.D. student at Princeton University in the mid-1990s. Kahera, who had learned Arabic in the Middle East and had worked for ten years as an architect in Saudi Arabia, knew that Omar’s autobiography, rediscovered while Kahera was at Princeton, was an international treasure. Most slaves in America had been forbidden to read and write, and here was a manuscript by a slave who had not only written a document of substantial historical interest but had done so in Arabic, with “a level of literacy that was strong and serious,” Kahera says. In the sweep of his prose, Omar could draw upon the teachings of two great religions and his own remarkable life on two continents with very different cultures. “All of that gave it incredible importance,” Kahera says.

The manuscript, which had been missing since 1920, was for sale at a gallery in New York, Kahera learned. “I was trying to get Princeton University to buy it,” Kahera recalls, “so I went to New York with one of my mentors, the late John Ralph Willis, to examine the document, and that was an incredible moment—to hold this thing in my hands.”

Princeton declined, but Kahera befriended Beard, the collector who eventually bought the manuscript. Because of that relationship, Kahera says, Beard has agreed to let Clemson keep the document for two years.

As Kahera sees it, the writing that began on the walls of that Fayetteville jail cell and flowed through the pages of Omar’s autobiography probably sustained the man, body and soul. Omar’s talents, Kahera says, helped to spare him from backbreaking labor, charming and impressing not only the Owen family but a long list of white luminaries, including Francis Scott Key, who came to visit the savant-like Omar. Owen brought him a Bible translated into Arabic and an English edition of the Qur’an, and apparently encouraged Omar’s erudition.

Why would a white slaveholder and his friends celebrate the talents of this one fragile man? We don’t know for sure, but Kahera thinks the answer might involve the rising sentiment at the time, in some quarters, favoring abolition. “I often wonder if the interest was to use Omar to help support the abolitionist agenda,” Kahera says. “Here is a slave who has a mind and can think, so he’s a human like us. He was exhibit A. Case closed. And Owen was trying to find out where Omar fit in the larger story. How many people were there like him? As far as we know, there were many.”

It’s been estimated that more than 20 percent of African slaves brought to the United States were devoted Muslims, many of them proficient in Arabic. But most slaves, no matter how literate, were forbidden to read and write. Omar was that rarest of men: a slave allowed his voice. “In some ways, he made himself free,” Kahera says, “by the power of the pen.”

This daguerreotype of Omar ibn Said was made in the 1850s, when he was about eighty years old. Image courtesy of University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Libraries.

This daguerreotype of Omar ibn Said was made in the 1850s, when he was about eighty years old. Image courtesy of University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Libraries.

An appeal to his God

Some scholars have questioned Omar’s fluency in Arabic, based on the occasional quirkiness of his phrasing. The phrase he uses for the Fayetteville jail, for example, is “the big house.” But Kahera has read the manuscript in Arabic, and he’s impressed. “I think he was very good with the language,” Kahera says. “He was able to remember the Qur’an because as a young boy he was immersed in it until it became indelible in his mind. So when he writes about Africa and his religion, that part was easy for him. But when he tries to write about Fayetteville, North Carolina, in Arabic, he’s having to listen to Americans speaking with a Southern accent, using English, which is not his native language, and then try to transliterate that into Arabic. Even so, he does a pretty good job.”

Omar’s literacy, in Arabic and English, was certainly good enough impress to the many visitors who stopped by Bladen County to ponder his considerable humanity. But Omar was doing more than showing off for whitey to save his own skin, Kahera says. He had embarked on what Christians might term a calling. A Muslim would call it jihad.

“There’s a concept in Arabic that’s known as the jihad of the pen,” Kahera says. “That word jihad has been misconstrued as ‘holy war,’ but it means ‘struggle.’ Omar’s was a jihad of the spoken word, a jihad of the pen.”

Kahera finds clues to this jihad in Omar’s compulsion to write on the walls of his jail cell. He was probably composing a kind of invocation, Kahera says, an appeal to his God. “Part of the Qur’an has this power to invoke what’s known as dhikr,” Kahera says. “This is something that would allow the force to be with you, so to speak. It allows you to reach out and petition your God to relieve you of your hardship.”

In an essay published in the Spring 2014 issue of the South Carolina Review, Kahera builds a compelling case that Omar was also writing to condemn, with considerable finesse, the institution of slavery. It is no accident, Kahera argues, that the central text of Omar’s argument was a chapter from the Qur’an titled Al-Mulk, which means “dominion” or “sovereignty.” Al-Mulk asserts that only God has dominion over people. Quoting its verses again and again, Omar consistently “undermines the practice of granting slaveholders dominion over other human beings,” Kahera writes.

In short, Omar was a slave denouncing slavery, along with its popular justifications in Christian doctrine of the time. This was dicey business, at best. Some scholars have assumed, after reading Omar’s writings and other accounts from the time, that he converted to Christianity during his years with the Owen family. Like many other Muslim slaves, Omar would have felt considerable pressure to convert, and he did attend church and read the Bible in Arabic. His conversion might have afforded a measure of tolerance and protection.

But Kahera isn’t convinced. “The big question is whether he converted to Christianity,” Kahera says, “and I take the position that he didn’t.” Even when Omar quotes the Bible, he introduces the scripture with a surah from the Qur’an. What emerges is a tapestry of both. Strange as it may seem today, Omar’s intermingling of Christian and Muslim texts underscores their common themes and their roots in the Abrahamic tradition, Kahera says.

“In some ways he made himself free by the power of the pen,” Kahera says.

“In some ways he made himself free by the power of the pen,” Kahera says.The power of a legend

Omar may indeed have allowed Owen and others to believe that he had converted, professing enough Christianity to pass as a convert without denying Islam. If so, he played the angles with considerable aplomb. “He became a legend,” Kahera says. “People looked at him as someone who had some kind of special power.”

What was the source of that power? “I draw a parallel between Omar and Martin Luther King, Jr., especially in his famous ‘Letter from a Birmingham Jail,’ to Omar’s struggles,” Kahera says. “When you put someone in very acute circumstances it raises the level of consciousness and you see the world in a way that you wouldn’t normally see it.”

It may be safe to assume that Omar could not have pulled any of this off without concealing, quite artfully, a great deal about himself and his motives. Kahera has many questions about the man behind the text. “I think there’s a secret side of him that we really don’t know,” he says. “I am curious for example about why he did not want to be repatriated to Africa when he had the chance. Some slaves did go back. I think he had reconciled himself to accept that God his creator had destined him to be at this place in this time under these conditions. I see him as a man of tremendous faith and piety.”

Omar was also a man who used his jihad of the pen to influence the very culture that enslaved him, Kahera says. “Maybe he thought his influence could bring some relief to others who were in the same condition he was, so they’d be looked upon as human.”

Akel I. Kahera is a professor of architecture and the associate dean for research and graduate studies in the College of Architecture, Arts, and Humanities. The manuscript of The Life of Omar Ibn Said, Written by Himself, will be exhibited in the Strom Thurmond Institute, Special Collections Library, October 1, 2014, to April 30, 2015. An exhibit reception is planned for 2–3 p.m., October 17.

Photos by Craig Mahaffey.