Of all human qualities

by Jemma Everyhope-Roser

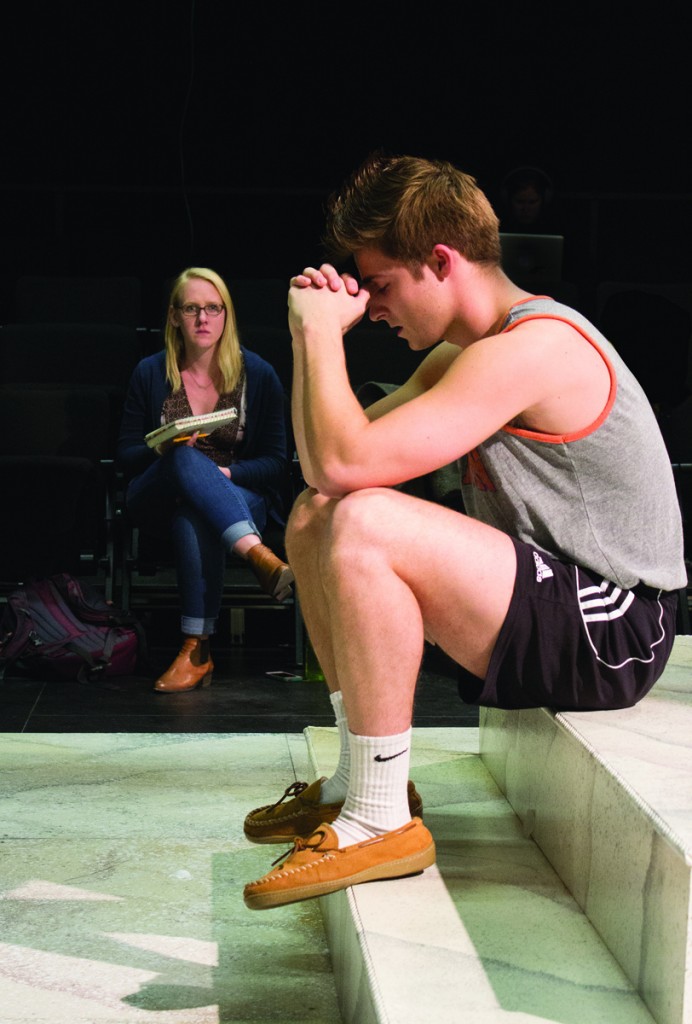

Survivors: Lydia (Julia Dingle) couldn’t bring herself to murder Nikos (Jonathan Bull). Their balancing act at last comes to rest in a tender embrace.

Survivors: Lydia (Julia Dingle) couldn’t bring herself to murder Nikos (Jonathan Bull). Their balancing act at last comes to rest in a tender embrace.From the first scan of script to the jitters of opening night, a play sweeps the faithful away on a journey of fearsome discovery.

the play

Big Love, by Charles Mee, is a modern remaking of The Danaids (also called The Suppliants) by Aeschylus. In Mee’s play, fifty brides, fleeing an arranged marriage to their cousins, seek refuge in a luxurious villa on the Italian coast. When the grooms catch the brides and wed the women against their wills, the brides murder their grooms. Only one couple falls in love and survives.

“About the same odds as today,” quips the summary on Charles Mee’s website.

Taking time to find their characters

Apparently ninety hours of rehearsal for a ninety-minute production is normal. The general rule of thumb for any production is one hour of rehearsal for each minute on stage. Or, as French says, “The amount of work that goes into an hour-and-a-half production is insane.”

As though ninety hours weren’t enough, many actors would meet outside the time they were strictly required to be in the Brooks Center, working together to memorize lines or to figure out what they wanted from a monologue or scene. Sometimes, they’d talk to their acting professor, Kerrie Seymour, which French always encouraged.

“We really dig into why these characters think the way they think, what their past was like, what is their favorite food,” Dingle explains. The girls would often get together in order to figure out their pasts, creating elements to the characters that were never written out in the script and would never be seen in the play, but that would give background and motive to each action the characters took in the script.

“Many of us do work outside of rehearsals because we want to bring our best when we walk into that rehearsal room,” Dingle says. “It isn’t just you trying to discover things. It’s everybody else and if you can bounce off of each other the result is going to be much greater.”

“Now that I am doing it I couldn’t see myself doing anything else,” Bonini says.

living and breathing

When I got into the program I had no idea what to expect,” Michael Bonini says. “I had never taken acting classes or been in college-level performances. But it’s shaped me quickly.”

A sophomore, Bonini has already had the chance to take acting classes, directing classes, and performing arts classes. He’s learned everything from the business side of performing arts to what casting agencies search for. He credits his leap in knowledge to the professors’ ability to communicate the technical aspects of art to students.

“It’s different than any other major because it’s the only major that you go into and you’re just submerged into it completely,” Bonini says. “You can ask any student and they will say that they spend about ninety percent of their time at college at the Brooks Center.”

Bonini, giving an example of his usual schedule, says that he’ll often come in around eight a.m. to practice monologues and for rehearsals. Then he returns again from noon until five for classes. Then, after a dinner break, he’s back again to rehearse from six to ten or so at night.

For Big Love, Dingle says, rehearsals began at the end of September and generally lasted four hours a night, five to six days a week. “We probably rehearsed well over ninety hours, I would think.”

how’d it go?

“We sold out five of seven nights, so I was really proud with how they did,” French says of the cast. “It was a lot of fun to watch their progress.”

As the actors performed live, they became more comfortable with the play. The ensemble solidified and the actors engaged with the audiences. French says that every night was completely different: “Wednesday night, people were laughing at everything they said. Then the next they performed it people were completely silent.”

Over the course of the run, the actors had to adapt not only to one another’s evolving performances but also to the audience’s mood.

next?

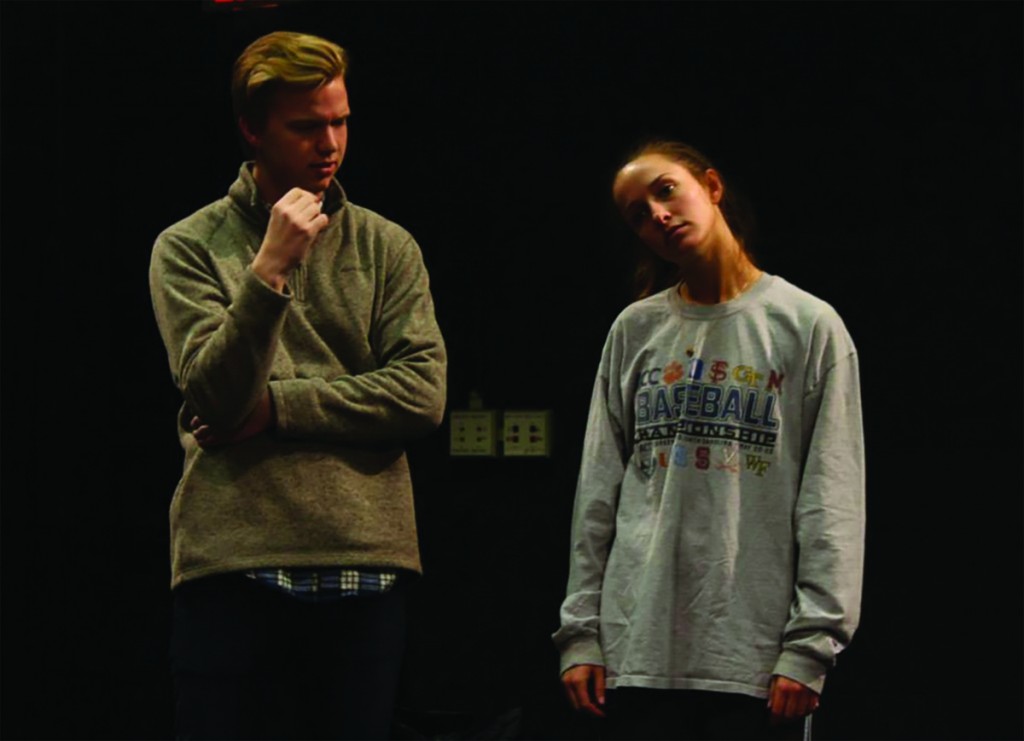

As you read this, many of the same actors will be working on their next big production, Eurydice, a play by Sarah Ruhl. These photos are from early rehearsals during the winter.

Lauren French (top of the photo above, with Claire Richardson, in blue, and Rebekah Swygert) will be guiding movement for the play as well as acting as the Loud Stone. Julia Dingle and Alessandro McLaughlin are working as assistant directors in the production. Michael Bonini will be playing Orpheus.

Adrian Eppley (below right) was cast as Eurydice. Jeremy Schwartz has the role of the father, and Jonathan Bull (below left) is the lord of the underworld and the nasty, interesting man. Kacey Bair is understudying as the Loud Stone and the Big Stone. This semester, Madelene Tetsch is studying abroad, and Drew Whitley pursues other interests.

Photos courtesy of The Clemson Players.

“He’s bringing in his own preferences and influences,” Tony Penna says, “and he’s trying to match the sound with the tempo and energy of those tantrums.”

November 14, 6:30 p.m., 49 hours until opening night.

Enter the black box theater from backstage and push aside a heavy fall of black velvet. The stage glows white. On it: faux-marble tiles framed by pale columns, a froth of cloth, a podium with its petite white tub, and, hanging high above, forty-seven wedding dresses. The stage divides the black-upholstered seating into what’s called a “tennis court” configuration.

You and I have walked in on what Lauren French calls “stage work.” French, the production’s director and a student at Clemson finishing her senior year, sits to one side in the front row. Her expression is attentive, her straight blond hair tucked behind one ear, as she calls instructions to the actors on stage.

The actors have just finished practicing the wedding scene so that the lipsticks can be smoothly handed off between the actors. Now French calls up Alessandro McLaughlin, who’s playing both Leo and Piero. She’s working with him on mannerisms, to make his two roles visually distinct.

French asks McLaughlin to run through a scene, instructing him to make his gestures bigger. “Come on, Leo’s hands don’t live in his pockets!” she calls, and he adjusts.

“I need to see some reaction there, Leo,” French says. “You’re about to get some!”

When McLaughlin successfully runs through the scene, complete with large gestures and lascivious looks, French congratulates him and says, “Can we see that again?”

At age fourteen, French focused her considerable energy on acting. She attended an arts high school where, as a junior, a guest artist introduced her to Charles Mee. But, only when that guest artist returned to teach Chekov and Stanislavski, did she think: “Oh, I could do theater. I could do this the rest of my life and be happy. And not just acting. I could try directing and work backstage…”

Her senior year in high school, she chose to direct a scene from a Charles Mee play—and followed that up by directing another scene from the same play last year.

“So,” she says, “he’s been a part of my life for a while.”

Tony Penna, associate professor and director of the theater program, says that every once in a while a student comes along who wants to pursue a career in directing. These students, once they’ve done the relevant coursework and proven themselves reliable, creative, and ready, get the opportunity to direct. It’s a lot of responsibility, but since French met the qualifications, she got offered the job.

That was December, 2013.

French immediately considered directing Big Love. The play appealed for many reasons. Great cast size. The female-to-male ratio, though not dead even, came close. And, most importantly, French says, “I really liked the story.”

French goes on to say that she believes the story challenges the audience to think about what “gender wars” mean today. But most of all, she values how Charles Mee doesn’t provide answers in his script, whether it’s about the paradigm he’s set up in his play or his stage directions. This openness and flexibility of the script allows French to discover, again and again, new ways of reading and staging the play.

Yet there’s more to starting out as a director than selecting a play. French decided to forgo using a dramaturge—a researcher who studies references in the script—and embarked on that job herself. If she didn’t understand it, she figured it out, line by line. French started by reading the play that Mee based his remake on, The Suppliants (which is also called The Danaids), a play by Aeschylus probably first performed around 470 BC. In the original, the women, rather than being central characters, appear only as the chorus. As for the grooms? They aren’t even in it. The group murder at the end? Now, that’s the same.

“Same basic structure, same basic idea, but updated and much more interesting,” French says. “It’s incredibly Greek. It’s epic. It’s larger than what we would do in contemporary play.”

But confronted with a confusing barrage of lines at the play’s finish, French turned to her advisor, Penna, to learn more. Penna has kept in touch with Les Waters, the director of the original production of Big Love at Actors Theater of Louisville in Louisville, Kentucky, and he asked Waters about those lines. Turns out, they reference The Pillow Book, an eleventh-century Japanese classic. Go figure.

While this information will never make an appearance in any performance, knowing the lines’ origin helps the actors understand what they mean and how they should be said.

At this point, Penna had already contacted Charles Mee about performance rights. Usually, playwrights publish their scripts and the theater becomes responsible not only for purchasing scripts but also for buying the right to perform the play. But unlike most playwrights, Charles Mee makes his scripts available online.

“If you’re doing his plays,” Penna explains, “and you can’t afford to produce a fully realized production, he does not expect you to pay for performance rights. You can do the show for free. But if you’re an established organization that has a budget, paying for performance rights is appreciated and expected.”

Clemson paid for the performance rights, because, as Penna stresses, that’s part of how the playwright makes his money and “it’s the right thing to do.”

Penna also set French up with the playwright, Mee, who told her that if she had any “burning questions,” he might answer them…or he might not. He told her that each actor and director must figure out the show on her own.

“That gave us the okay to really take it on and make our own story with his words,” French says. She found this liberating.

French also took her research one step further while studying abroad at Accademia dell’Arte in Arezzo in Tuscany, Italy. “That gave me a great jumping off point when starting in on Big Love,” French says, “because I knew going in that I was directing Big Love, so I got to research while I was there.”

French took the time to visit the Italian coast so that she could get firsthand experience of the play’s setting. She explored Cinque Terre on Italy’s mountainous western coast, near to the play’s actual location, taking photos to carefully analyze the city’s elements.

“I got to get a feeling of the culture, the art, the people, the food,” French says. “All these wonderful things have enriched the process.”

When French returned, she began casting the play and met with the designers. Immediately she realized that the crisp, film-like image she’d had in mind wouldn’t work. In a lot of realistic plays, French explains, things are set for you. But in Big Love, Mee writes the setting should be:

If Emanuel Ungaro had a villa on the west coast of Italy, this would be it:

we are outdoors,

on the terrace or in the garden,

facing the ocean:

wrought iron

white muslin

flowers

a tree

an arbor

an outdoor dinner table with chairs for six

a white marble balustrade

elegant

simple

basic

eternal.

But the setting for the piece should not be real, or naturalistic.

With all of that information and these options before them, French worked with Shannon Robert, a faculty member and set designer, to figure out what they both wanted and how it might fit with French’s vision (see art for the fearless).

And to communicate that vision, French had to learn a new vocabulary to speak with designers. Penna states that it’s to her credit that she never shied away from her position, comfortably talking to her faculty designers as equals and steering them toward her vision (see a transformation of light).

“In this department we focus on professional development and preparing students for the professional world,” Penna says, “and she has the kind of confidence that will serve her very well after she graduates.”

Being able to gauge Clemson’s resources, not only for set design but also in terms of personnel, helped French lead the production effectively, especially when it came to casting the show. French says, “We’re very fortunate here because we get to see each other’s work all the time. So I had an idea when choosing for the show: Will we be able to have the people to play certain roles? Will I be able to cast this show? Yes.”

Auditions began. Actors showed up with roles in mind. French made final decisions.

November 15, 6:30 p.m., 25 hours until opening night.

When you take a seat on one of the black chairs, you’ve got the chance to watch the actors work through a “fight call.” Michael Bonini, the actor playing Constantine, throws himself into a headstand while the other two leading men, Jonathan Bull, playing Nikos, and Jeremy Schwartz, playing Oed, support his feet. Bonini almost tumbles right onto his head, and the three try again.

“Guys, slow down!” Liz Haynes calls. “You all right?”

Haynes, as the stage manager, organizes productions, rehearsals, production meetings, and performances. Because of her, all the actors are at the right place at the right time. She calls light cues and sound cues, too. Or, as Penna says more simply: “She makes it all happen.”

Right now, Haynes is frosting the top half of a wedding cake that will be cut during the wedding scene. The lower half of the cake, also still under construction, consists of Styrofoam, plastic flowers, artificial pearls, and caulk.

But they’re not going to a wedding; they’re going to the after party. In this case, a brutal massacre. Haynes shouts out to the girls, “If you don’t have knives, grab ’em,” and the actors begin to assemble.

Kacey Bair, playing Olympia, flips open her knife and fumbles. The actors play through the scene again. This time Bair goes through the motions of slitting Schwartz’s throat. The two women who’ve successfully murdered their male counterparts stand over their kills, at a loss, while the only surviving couple cuddles amidst the pools of red light.

With fight calls and scene work done beforehand, French releases the cast for a dinner break.

Next up? The dress rehearsal.

Afterwards, Penna comments that the actors let pauses go on too long, causing the show to run over. The actors gather around French to talk excitedly about how it all went. The faculty, who’ve taken extensive notes on every problem that must be solved before opening night, drop into the conversation to hand over their pages.

Robert, her notes in hand, tugs at the bunched tulle at the back of an actress’s wedding dress. She wonders, aloud, “What about the problem with this dress? How do we fix it?”

The actors are all silent for a moment. This has been an ongoing issue, clearly.

“Burn it,” someone mutters.

French heads over to the green room with the actors to discuss each issue individually so that that the group can brainstorm solutions.

The green room, with its sturdy couches, bric-a-brac, and kitchenette, looks like a combination between a dorm common area and an office break room. The director, actors, and actresses seat themselves in a circle, some flopping onto the couch, others pulling up chairs.

“How do you feel about the run-through?” French asks.

After listening and responding to her actors’ feedback, French goes through the notes that the faculty members and stage manager have given her. French tells Bair that she’s been playing with the other actresses’ hair too much during performances. This distracts the audience.

“I just like that hair play,” Bair admits.

“It’s my job to pull you back,” French says and goes on to speak with Bonini about the scene where Thyona bites Constantine on the hand. French tells Bonini to wait a little to react after the bite, to give the audience time to see the bite and make sense of Constantine’s reaction.

“I don’t know about ya’ll’s pain,” Bonini comments, “but my pain is immediate.”

“Just wait a beat,” French instructs, and Bonini nods thoughtfully. To an outsider, it seems counterintuitive that an artificial pause will end up looking more natural than an immediate reaction. But it does. French turns to Madelene Tetsch who plays Thyona, and says that she needs to play up the taunting butt dance a little more. The other actors tease Tetsch.

“I’m fine with my butt,” Tetsch comments impatiently, “but if I pull up the dress, the knife shows.”

French considers this. The knife, strapped to the actress’s thigh, is supposed to be concealed before the post-wedding murder scene. French says, “Don’t do it then.”

“It’s in the script,” Tetsch says.

“If it doesn’t work,” French says, “don’t do it.”

As the team finishes discussing issues and solutions, French brings the meeting to a close. When she asks the actors if they have any questions before opening, there’s an anxious eek from the actors and a little playful yelping. French relates how Italians say “in bocca al lupo” or “in the mouth of the wolf” to mean “good luck!” The correct response to this is “crepi” or “kill it.” The group promises to wish each other luck before each show the Italian way, and then French disbands the meeting.

At opening night tomorrow, French’s job will end.

After French had her cast assembled, she set the actors to reading Charles Mee’s script. It can be easy to make a reading flat and boring, so French says that one of the largest leaps she saw was from “page to stage.”

“When I first read the script I didn’t realize how funny it was,” says Julia Dingle, who plays Lydia.

After that initial read-through, French led the actors through what’s called “table work,” which usually consists of sitting down and talking a scene through. “With every scene we dug through all the background,” Dingle says, “and all the meaning and all the subtext that you may or may not get as an audience member but you need to know as an actor.”

But, instead of remaining seated at a table, French took a more innovative approach.

“I had them get up and talk about it,” French says, “because if you have them sitting down for too long it could be detrimental, especially in a piece like this that calls for a lot of physicality.”

Bonini says it was the most physical production he’s ever done, and that his background in gymnastics helped him tackle the role. He adds, “But it was such an awesome experience to be able to tell the story through more action than text.”

After the table work, French and the actors block out the play scene by scene. Blocking, an exhaustive and involved process, establishes what each actor does when.

Blocking decisions might be tiny but can have huge ramifications. For every scene, the director and the actors must decide where they stand, why they’re standing there, if they move to cross the stage, what might motivate this cross, and much more. It can include the choreography of fights and slaps. It can involve handing off items so that each motion seems natural, unforced, and in character. In one scene, a character may need to step backward and sit down on a chair. Missing the chair would be funny in all the wrong ways—and would miss the point of the play.

What’s more, French had to work out the sight lines. She’d watch each scene from different rows and seats to ensure that everyone in the audience would get an unobstructed view. French says, “You have to watch everything that’s going on. You have to be aware of the whole picture. And I think it’s like your focus expands to the whole stage.”

French had the first rehearsal with all of the actors together. But along the lines of the play, she split the actors based on gender. The males rehearsed together and the females rehearsed together. The first exception? Drew Whitely, playing the gay character Guiliano, appears on stage only with the women. The second exception? The actors playing the surviving couple, Dingle and Bull, continued to work together.

“It was very interesting when we all came back together,” Dingle says, “because we had all been developing our characters. It was fun to watch all these characters fill out and take shape.”

At this point, the blocking had been worked out right up until the point of the large fight scenes. The director and the actors had to develop a choreography to get their point across, and they needed help to do that—from an expert.

Bill Muñoz, a professional fight choreographer, was brought in to instruct the actors. He did most of his teaching at the beginning of the third week in, Bonini says, but also dropped by a couple of nights before opening to clean up the scenes. Under his tutelage, the actors learned how to throw ninja stars, how to safely fall and throw yourself to the ground, how to kick, and how kill each other. Everyone had a distinct and specific method of murder.

“It was not only good for the show,” Bonini says, “it was a good learning experience for the actors and people involved, just to see what goes into making these things look real but still safe.”

Regarding blocking specific scenes, French says, “If I had a set moment I really wanted to see happen, I would tell them how I wanted to see that happen. Like the Lydia and Niko scene. I wanted the kiss to happen near the swing. And I wanted him to be pushing her.”

But for other scenes, French only set the boundaries. She wanted actors to know the scene’s stakes but she “let them run with it,” telling them to get out there and give it a try. The actors would tackle the scene again and again from different angles until French found a version she liked. Then she’d have the actors rehearse that version, making minor adjustments.

“I would offer suggestions,” French says, “but I really wanted to make them make their own choices.”

French admits that it can be hard, as someone with acting experience and training, to sit back and let the actor work through a moment. “I know what I would do in that moment. I want to tell them to do it. But they’re coming from a completely different place and I have to find ways to make choices that are okay for them.”

Yet her training in acting has also helped her give the actors productive notes and guides. Without that training, French says, “I would be lost.” Both Bonini and Dingle agree French’s approach gives actors a say in what they want from their characters. Dingle says that French created work from what felt natural to the actors. Bonini says that he worked with her to hone his monologue into something he could really be proud of.

“It was the first time I had worked with a student director,” Bonini says, “so I was super excited for that new experience. It was especially cool and interesting because it was very collaborative process. We really came to middle ground well.”

“She is very actor-oriented,” Julia Dingle explains, “in that she lets you do what you’re going to do and then she takes what she likes from that and works with it.”

And through the actors, French had the opportunity to see characters from new angles. In particular, the actors’ portrayal of two characters, Thyona and Constantine, deepened her insight. Thyona and Constantine, arguably the most aggressive characters in Mee’s play, initially seemed extremely angry. But French came to understand that these characters had been conditioned by society to take their ideological positions and weren’t necessarily happy with the worlds they inhabited.

Constantine’s monologue, in particular, has some harsh language and sentiments:

so it may be that when a man turns this violence on a woman

in her bedroom

or in the midst of war

slamming her down, hitting her,

he should be esteemed for this

for informing her

about what it is that civilization really contains

As French says, “He’s using this speech to justify beating women, and it’s not okay. But you see that, oh wait, he’s also human. You have to look at it through his point of view as well. Which was hard for me, and really scary, because I didn’t want to see that side.”

For all the harsh qualities and physical drama, French found herself surprised by the other elements that Bonini fed into the character. “He’s brought a lot life to it and a lot of the softer qualities that you need,” French says. “Otherwise, people wouldn’t listen to what he’s saying.”

Michael Bonini, the sophomore playing Constantine, says that he’s played characters like this before. His familiarity with this type of character did help him, but Mee’s surrealistic exaggeration brought this character to a whole new level for him. He says that it could get outright frightening, because of the “intensity of the character.”

“The first thing I do is I walk on stage and choke Thyona’s character. So I mean that can get kind of intimidating,” Bonini says. “Then after that I throw her on the ground. That took a lot of trust, rehearsal, and choreography to really get perfected and put together well.”

French made a conscious decision not to dictate but to collaborate. Getting actors on their feet, seeing what worked, and pressing the actors to develop their own solutions became key to her directing style. “The fact that I have to talk to each actor differently has been a huge surprise to me,” French says. “The fact that I’m not automatically given the respect and trust that I would get, but that I have to earn it. Which was so frustrating at times! But once I earn that trust, it’s really rewarding.”

November 16, 7:30 p.m. Opening night.

The audience sits quietly in the dark while the soft sound of surf plays throughout the small space. An actress enters the theater from backstage, right next to the main doors. She ventures across the stage, and behind the soft gauze around the podium, undresses in the dim blue light. Setting her wedding dress aside, she climbs into the tub. The sound of real water mingles with that of waves while we wait for the play to begin.

As an audience, we are divided along gendered lines below wedding dresses, the men sitting on one side of the stage, dyed blue with light, and women beneath the pink on the other side. We echo the thematic contents of the play, collaborators in this elaborate act of creation.

French’s work is done. The designers have stepped back. The actors must go on, working together each night to rivet the audience, to elicit thought and sympathy. Tonight, they fumble their lines before their full house. Only a little.

I can tell they’re nervous, because I’ve seen them work out these scenes together, but I’m not sure if anyone else can. As they warm to us, surprised and delighted when their jokes cause a burst of laughter, we warm to them.

The truth is, we’re all here for the same reason.

Because, in the end,

of all human qualities, the greatest is sympathy—

Tony Penna bides in a liminal space, between light and darkness.

For a brief update on what the Clemson Players have been up to in their recent production of Eurydice, read about Paige Foley’s case study here and learn a little more about the theater department.