why the pitcher does research

by Neil Caudle and Brian Mullen

An athlete prepares for a future in baseball’s number-crunching culture.

When Matthew Crownover takes the mound for one of his starts, he doesn’t think about analysis. Any other day, he can tweak his pitching mechanics or analyze the tendencies of opposing hitters. But when it’s his turn to pitch, he sets analysis aside. He takes the ball and throws it to his catcher. Anything else would just get in the way.

But Crownover knows very well that off the field the business of baseball today is all about numbers and analysis. Ever since Billy Beane brought a statistics guru to the low-budget Oakland Athletics and propelled the team into the playoffs (inspiring Michael Lewis’s book Moneyball), major-league clubs have been waging a stats-and-analysis arms race, hiring their own statisticians to crunch the numbers and advise them on every aspect of the game.

So Crownover, who is planning for a future in baseball after his time on the field, saw an angle for his career.

An eye on the dream job

“I know baseball’s not going to last forever,” he says about playing the game. “So whenever it’s over I want to have a job to do. And one of my dream jobs—aside from being a coach one day—would be to work in a front office somewhere, and be like a general manager. These days, you have a lot of analytical guys who run the front offices, but there are also other, old-school guys who are baseball guys. I would be more like the old-school guys because I’ve played the game and been around it for a while, but I thought it might help to have a little background in some of these statistical things, to have a little bit of résumé.”

In the fall of 2013, Crownover was taking a class in sports communication and began talking with Jimmy Sanderson, who directs the B.A. program in that area. “He knew who I was, and he comes to the games,” Crownover says. “So I asked him if he was interested in helping me with an independent study.”

Yes, Sanderson was interested, and he liked the topic Crownover pitched him. “I had some ideas about how each club constructed its team,” Crownover says, “and whether it was more effective to build through free agency or build through homegrown players. Which positions were more effective, homegrown versus acquired?”

Sanderson and Crownover used statistical modeling to investigate MLB roster construction for all playoff teams from 2009 to 2013. “We wanted to know if there are certain positions that produced more significant results based on whether the player is homegrown or acquired,” Sanderson says. The researchers created variables for player position, league affiliation, how the player was acquired, and wins above replacement (WAR) value, a statistic that summarizes a player’s total value to the team.

The tests revealed that left fielders, relief pitchers, and catchers who were homegrown had higher WAR values than those who were acquired. The researchers also found that it was even more advantageous for American League teams to develop their second and third basemen from within their organizations.

Winning with statistics

Winning with statistics

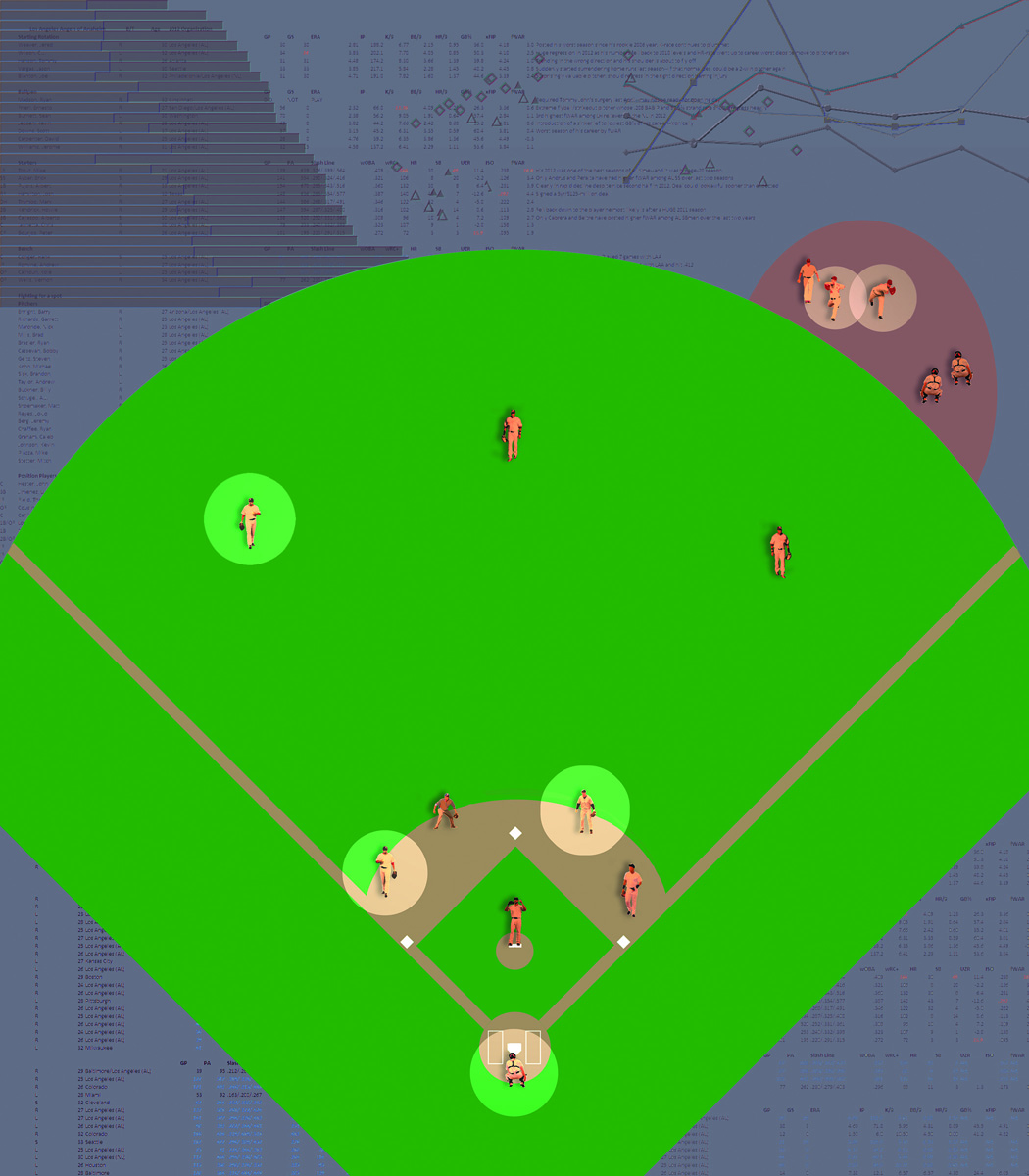

Today, stats drive decisions in Major League Baseball. Should a team grow its own players through its farm system? Or should it trade for new talent and sign free agents? Sanderson and Crownover found that teams fared best when they cultivated homegrown left fielders, relief pitchers, and catchers. In the American League, teams also found an advantage using homegrown second and third basemen. Image by Neil Caudle.

Where homegrown players pay off

“The results show generally that teams need to protect their homegrown players at these positions and focus acquisition efforts on players at other positions,” Crownover says.

He and Sanderson presented their results at the 2014 conference of the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR) in Houston, Texas, winning the USA Today Sports Weekly Award for the best poster presentation at the conference.

Over the fall and winter, the researchers expanded their research to a thirty-year period, 1982–2013, and are running a statistical analysis of the data.

“This research is an example of the ways that sports are being quantified,” Sanderson says. “Baseball was the early adopter, but now most professional sports leagues are using advanced metrics to try and optimize player development and roster construction.”

For Crownover, the project has helped him strengthen a weakness. “I’d never been big into the stats thing. But if I really want to get into this business one day, with all of these kids who are coming out of Harvard with Ph.D.s and are running baseball, I kind of want to know what’s going on. I want to be the guy who knows the baseball side, and has played at a high level—in Division One and maybe even some professional ball. But I also want to be the guy who, while he was in college, tried to do something on the analytics side. So he’s got a baseline understanding of what we’re doing here; he’s going to understand both sides. And that’s what a communications major can do, right? Talk to both sides?”

Matthew Crownover, a junior from Ringgold, Georgia, is majoring in communications studies; he is also a left-handed pitcher for the Clemson Tigers. Jimmy Sanderson is an assistant professor and director of the Sports Communication B.A. Program in the Department of Communication Studies, College of Architecture, Arts, and Humanities.