the bullies of cyberspace

story by Jemma Everyhope-Roser

illustration by Stephen Durke

Kids get hurt when spite goes viral.

Suzannah Isgett—her nickname is Zan— was an honors student, a self-described bookworm who attended a public arts school. Her ordeal began in the eighth grade when two cute guys took an interest in her. She dated one of the boys and hung out with the other. She had no idea that two other girls had laid claim to them. The girls tried to turn the boys against Zan, but when that didn’t work, they decided to befriend her. Zan had no interest in gossip and popularity contests. She avoided them. The girls started texting her, insulting her over AIM and MySpace, and excluding her at school. They’d ask Zan’s friends to sleepovers and make sure than Zan knew she wasn’t invited.

“It was a small school. I’m sure everyone knew it was happening,” she says, and people even joined in. Boys threw rocks at her. Girls disparaged her appearance. The teachers felt they couldn’t intervene, because most of the harassment occurred outside of school.

“It felt like my world was over,” Zan says. “These girls wanted to see me suffer.”

After eight months, it ended when the boys left Zan for the popular girls.

Zan says that the experience was one of the worst in her life so far, but she came out of it with a deepened understanding. Studying with psychologist Robin Kowalski helped her put it into perspective and eventually led her to apply for a Ph.D. in social psychology. She works in the Positive Emotions and Psychophysiology Lab at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where she studies how genes influence positive behaviors.

A “mean, mean girl”

Mackenzie White (not her real name) had a good life. She was popular, her parents came to her basketball games, she had dinner with them every night, and she had a computer in her room. She says she started cyberbullying in seventh grade to maintain her superiority.

Mackenzie mostly harassed people over AIM. She’d create fake screen names. Sometimes she’d make the names similar to other people’s and impersonate them. Sometimes she’d pretend to have a crush on someone, leading them on and then disappointing them. She only harassed people she knew, though sometimes she did it anonymously. Her friends did it too.

“Really, I was just a mean, mean girl. I had no concept of others’ feelings.” Mackenzie remembers chatting with another friend of hers online. Her friend said that her comments were hurtful, that she was crying, and Mackenzie told her, “And I’m laughing at you.”

Once, she found the results to an online love quiz and learned that a male friend was bisexual. She printed off the results and distributed them around the school, outing him without his permission. But, other than that, her online actions didn’t really transfer over into traditional bullying. She says, “It didn’t seem like it played into real life. I would have never been as mean to someone’s face as I was online.”

Today, Mackenzie White lives abroad and works at an international school as an academic advisor. She also teaches life skills to middle school kids and includes internet safety and cyberbullying prevention in the curriculum, all as a result of the research she’s done with Robin Kowalski.

In the end, both Isgett and White are lucky. No one died. Sometimes, when cyberbullying bleeds over into real life, the consequences can be deadly. Tristan Christmas died at age eighteen after a “happy slapping” incident, when his assault was filmed and posted online. Ryan Patrick Halligan (www.ryanpatrickhalligan.org) died by suicide at age thirteen after years of physical bullying culminated in a cyberbullying episode where a girl pretended to like him online, copied and pasted his chat confessions to her friends, and then mocked him publically for it. The reasons leading up to a suicide are often very complex, but cyberbullying can be a tipping point.

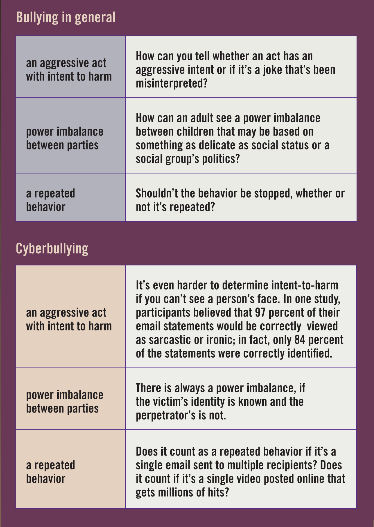

To count as bullying, the behavior has to meet the following three qualifications: It must include an aggressive act to harm, a power imbalance between parties, and repetition of the behavior. But, as you can see from the table, each part of the definition poses its own problem for a well-meaning adult.

What’s more, the commonly used definition is further complicated by varying state-to-state legal definitions. Some bullying behaviors cross a legal line and may also meet the legal definition of harassment or assault. And although no federal law directly addresses bullying, sometimes bullying may count as discriminatory harassment when it is based on race, national origin, color, sex, age, disability, or religion.

If you thought that wasn’t enough, bullying’s newest mode, cyberbullying, adds its own host of complications.

The problem with defining bullying—and proving that’s happening—is yet another reason why reacting after the fact is not enough. Cyberbullying can be even harder to track, although it’s certainly not as anonymous as many adolescents believe it is. Between the underreporting mentioned in these pages and the burden of proof resting on the victim, it can seem almost impossible to stop bullying.

As Kowalski and Limber’s research in schools shows, prevention is what works.

For more resources on bullying and cyberbullying, please visit www.stopbullying.gov, www.clemson.edu/olweus, or www.cyberbullyhelp.org.

The search for solutions

Cyberbullying can be hard to understand because the individuals involved can react so differently. Amanda Todd, a Canadian teenager, was targeted anonymously with an explicit photo taken when she was thirteen. She changed schools several times but the harassment followed her—and eventually she committed suicide. You can see her tell her story on YouTube. The video, posted a month before her death, now serves as a memorial.

Although cyberbullying is not as prevalent as traditional bullying, especially verbal bullying, approximately 18 percent of surveyed students reported being a target of cyberbullying at least once within the last two months. About 11 percent said they had cyberbullied someone at least once within the last two months. As adults, most of us wouldn’t stand for being harassed, humiliated, or assaulted at work or online. Why are students expected to ignore what adults wouldn’t?

“All children should be able to interact in school settings without fear of being harassed or humiliated,” says Susan Limber. She is a developmental psychologist who started her career focused on violence against children. She now studies bullying and children’s rights. Currently, she oversees the dissemination of the Olweus Program in North and South America, analyzes data from a nationwide database of bullying among children and youth to understand shifts in bullying, and provides consultation to the federal government’s efforts to address bullying. She argues, in one of her most recent papers, that progress against bullying in schools represents some of the most important advances in children’s rights since the child labor laws.

But, she says, “I am not in favor of criminalizing bullying.”

Limber’s collaborator, Robin Kowalski, began her career researching traditional bullying but grew interested in cyberbullying about ten years ago. She uses a variation of the Olweus Bullying Questionnaire to study the prevalence of cyberbullying among adolescents and adults—it’s more critical than ever to understand cyberbullying as more states enact legislation about it.

In response to legislation, schools often search for appropriate responses to bullying. Unfortunately, all too often these schools develop zero-tolerance policies, which demand suspension or expulsion after bullying. Often, these solutions only make the lives of already at-risk kids worse and do nothing to improve the situation at school.

But bullying and cyberbullying can’t be overlooked with a mild “kids will be kids” attitude. The negative effects from cyberbullying appear to be similar to those from traditional bullying, Limber says. Children who are bullied are likely to develop depression, low self-esteem, internalize their problems, and have lowered academic performance. Children who bully are at higher risk for externalizing problems, violent behaviors, drug use, and juvenile delinquency.

This is a problem for everyone. And it has to be solved.

Not a conventional conflict

Kowalski and Limber have worked with youth-advocate Patricia W. Agatson on the most recent edition of their book, Cyberbullying: Bullying in the Digital Age, which discusses not only current research but also its practical applications. Not all well-meaning efforts to prevent or stop bullying and cyberbullying work (if you want to know about programs that do work, visit the resources given at the end of the article). Some conflict resolution and peer mediation programs only force the bullied child to spend more time with the child who is victimizing them. Often, they resolve nothing; bullying is not a form of conflict.

Educators face a unique challenge when it comes to both bullying and cyberbullying. In addition to traditional bullying problems, evolving technology and new social media platforms make it hard for educators to keep up with adolescents, who were born into the Internet era and are often very tech savvy. By eighth grade, at least 80 percent of students have a Facebook account. In 2010, around 93 percent of twelve- to seventeen-year-olds spent time online; 63 percent of them spent time online every day, and 36 percent went online multiple times a day. The average teen sends fifty text messages a day, though for more intensive users it averages three thousand texts a month. Texting has surpassed IM as the leading form of communication among teens.

Cyberbullying is as real as traditional bullying—and as painful. Online, perceived anonymity is a dangerous weapon. If a victim isn’t aware of the perpetrator’s identity, then anyone and everyone could be a possible harasser. A single perpetrator can work under fake screen names so that the victim feels like the target of a larger conspiracy. A hijacked account can be misused to attack an entire contact list, permanently breaking friendships. Misinformation and poisonous rumors can be circulated with a single click. Easy access to private information, such as phone numbers and addresses, can make online death threats truly terrifying.

“Around fifty percent don’t know the perpetrator’s identity,” Kowalski says. “At least, with traditional bullying, you can attempt to avoid a bully because they’re identifiable.”

Kowalski and Limber are both trying to understand the overlap between online and offline behavior.

When bullying is reported, educators can and should approach the children’s parents to discuss any allegations with them, Kowalski says. Parents can play a critical role in addressing bullying. But not all parents are responsive. Some approve of bullying as a way to “toughen up a kid for the real world” or want their kid to “learn how to defend themselves.” Other parents may be overprotective. Parental overreaction, such as removing a bullied child from school or confiscating electronics, may only make a child more isolated and reluctant to report bullying when it does happen. Limiting children’s technology use when they’re being cyberbullied only makes the targets feel as though they’re being punished for talking about it at all.

Bullying is often underreported because children don’t want to be perceived as tattletales and they don’t want to get their peers in trouble. The harsher the penalties, the more pronounced this is. If children do tell someone, they’re most likely to tell a friend or a sibling before ever approaching an adult. Adult intervention to stop bullying can be helpful but it isn’t a long-term solution. So what is?

Indulging the novelty of power

“Prevention,” says Limber, succinctly. Stop it before it happens at all. Kowalski and Limber have developed curricula on cyberbullying for elementary, middle, and high school students, to be used as part of a comprehensive bullying-prevention effort in a school. Understanding a school’s climate and culture is critical to preventing traditional bullying and cyberbullying, Limber says. Educators and parents should be aware of the patterns in each school regarding gender, race, and insider/outsider groupings. It’s important for adults to have high expectations of good behavior and to reward children. A reward, depending on the school or the adult’s philosophy, could be anything from a verbal acknowledgment to a gold star or an ice cream party at the end of the year.

In the younger years, Limber explains, bullying is more prevalent because children are still learning how to interact appropriately. Children, not yet powerful in the adult world, are playing with the novelty of having power over others. In elementary school, it’s easier for older students to wield power over younger students who aren’t as able to defend themselves.

Kowalski emphasizes how important it is for kids to talk about both traditional bullying and cyberbullying. She recommends a change in curriculum so that there can be class discussions. Peer leaders are also important. So is teaching kids how to deal with bullying when they encounter it in person.

“We know so little about the bystander’s role,” Kowalski says. “The vast majority of people aren’t victims or perpetrators, they’re bystanders, and they’re the ones who can make a critical difference.”

When it comes to cyberbullying, bystanders can also make a difference by stepping in. But kids need to know when it’s appropriate to respond to bullying online, Kowalski says; parents and teachers should teach online courtesies, known as netiquette, as well as real-life pleases and thank-yous. Parents may feel technologically impaired sometimes, Kowalski says, “but the easiest way for us to keep up with changing technology is just to ask our kids about it.”

Kowalski was involved in a focus group in which a kid said, “I want supervision, not snoopervision.”

Beware the flirty pictures

Monitoring online behavior at regular weekly intervals by viewing browser and chat history can show parental attentiveness without invading a child’s privacy. Asking what they’ve been doing and talking to them about password security and the dangers of posting identifying information online can help too. Making sure they know the difference between trolling and a genuine threat is also important.

Susan Limber (left) and Robin Kowalski: Evolving technology and new social media make it hard for educators to keep up with what students are doing to each other in cyberspace.

Susan Limber (left) and Robin Kowalski: Evolving technology and new social media make it hard for educators to keep up with what students are doing to each other in cyberspace.And, if you thought the birds-and-the-bees talk was bad, try talking about sexting. But kids need to know that keeping flirty pictures of peers on their phones can count as possession of child pornography and could earn them a prison sentence and a place in the sex-offender registry. The legal consequences for online behavior are very real and could permanently affect a child’s life. How can any kid be expected to know that without being told?

Robin Kowalski and Sue Limber are both parents. Kowalski has twin boys, aged twelve, and says that personally she’s trying to focus on cyber safety. She relates to me an instance where she overheard her boys talking with another friend, who wanted to log on their computer. He asked for their password. After a long hesitation, her sons refused.

“But we’re best friends!” the other kid argued, hurt.

Kowalski came in and explained that her sons weren’t allowed to give out their passwords, getting them off the hook. She says she had a good talk with them about it. It can be hard to refuse someone you know—and otherwise trust—with details like that. This can be difficult for a kid to accept, when the kid desperately wants to believe that friends means friends forever.

As a parent of a seven-year-old girl, Limber has seen the issues she studies with new eyes. She wants to say that she’s very impressed with how local schools handle the issue.

“I think there’s really been a change in the time I’ve been working in the field,” she says. “I’m very encouraged.”

For more resources on bullying and cyberbullying, please visit www.stopbullying.gov, www.clemson.edu/olweus, or www.cyberbullyhelp.org.

Susan P. Limber is the Dan Olweus Distinguished Professor in the Institute on Family and Neighborhood Life (IFNL). Robin Kowalski is a professor of psychology in the College of Business and Behavioral Science. Jemma Everyhope-Rose is the assistant editor of Glimpse.