Creativity can make art of science

Neil Caudle

Christina Hung’s microscopic interventions

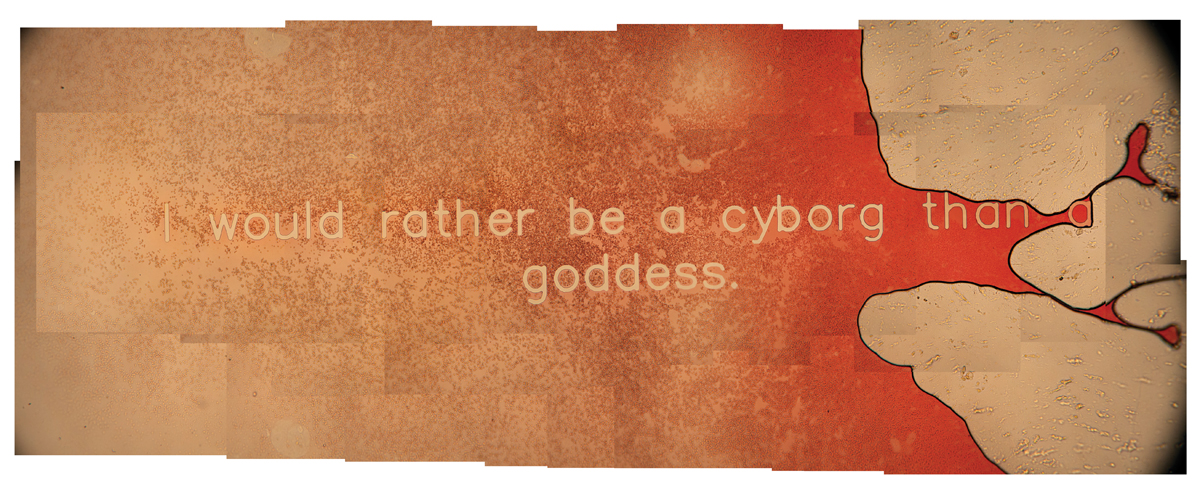

Goddess|Cyborg, by Christina Hung, is a panorama micrograph of blood cells and a message imprinted using PDMS stamps, patterned pieces of polydimethylsiloxane. Kirk Pirlo, a former graduate student in biophotonics, helped Hung with the technology.

Even in childhood, Christina Hung had an interest in science. A microscope, she learned, could help her see what was hidden in plain view. Today, she uses micrographs—photographic images on a microscopic scale—to compose her art.

“I enjoy very much photographing things at the microscopic level that I can perceive with the naked eye,” Hung says. “Think of a leaf, for instance: It has a familiar surface and color. But with the tools of microscopy you can see an entirely different object, an entirely different world. It forces us to question what we think we know about a leaf, and this is something that contemporary art and scientific visualization have in common.”

Working at the intersection of art and science, Hung “tweaks the methodologies of science,” she says. Modern scientific tools can focus on a sample, convert its properties to data, and render the data automatically as images. Hung uses the tools but skips the automation. She intervenes.

“I’m looking at things and making the kind of interpretive decisions that can’t be automated,” she says. “I gather my own data using modified microscopic imaging techniques, and a blend of scientific and artistic methodologies. ”

Sometimes, she works directly with scientists, because they offer some necessary tools and expertise. Kirk Pirlo, a former graduate student of Bruce Gao in biophotonics, helped Hung try to write words with neurons extracted from chick embryos. The writing proved elusive, but she was able to create micrographs for the first time.

Lately, she’s been stitching micrographs into panoramas that, with magnification, seem as enormous as walls.

In the microscopic world, she leaves her mark, her brief and poetic reminders that despite the aspirations of scientific objectivity we experience the world—even the world beyond ordinary sight—in a context of history and culture, with a particular point of view. As an artist and a feminist, she intends to claim some of the territories of science on behalf of other cultures and mind-sets, starting new conversations about the nature of the world.

All of this makes her a rather unconventional academic, an artist and critical feminist with science on her mind. She laughs and says, “If there is a crack to fall into at Clemson, I fall into it.”

As one of her college’s creativity professors, Hung often finds herself in conversations about what it means to be creative. “I generally take the stand that creativity is deeply tied to diversity,” she says. “When we talk about creativity, we usually talk about how we shake ourselves up and break old habits, how we interrupt ourselves and introduce new ideas. What I add to the conversation is the idea that diversity, as it plays out in society, also helps drive creativity.”

Boxed, from the series The Nabakov Index, 2013, by Christina Hung. Fragmented and contained Papilio glaucus.

Christina Nguyen Hung is an assistant professor of digital art in the College of Architecture, Art, and Humanities (CAAH). Bruce Z. Gao is an associate professor of bioengineering in the College of Engineering and Science. Russell Kirk Pirlo completed his Ph.D. at Clemson and now works in tissue engineering as a scientist with the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory. Hung received support for her work from the Clemson CyberInstitute, CAAH, and the Clemson University Research Grant Committee.