What really happened to the Hunley?

stories by Frank Stephenson

It took two full days after the Housatonic’s decks were swimming with fish before the Confederacy’s top brass in Charleston asked the obvious question. Nearly 150 years later, it’s still the mystery that a dozen years of studying the Hunley’s bones has yet to solve.

When the vessel was raised in the summer of 2000, optimism was sky-high among legions of Hunley fans that one of the most curious mysteries of the Civil War was on the brink of being solved. Twelve years later, the mystery has proven impervious to an unrelenting, point-blank barrage of some of the best archaeology and conservation talent in the world, largely because the submarine itself is still hidden under heavy concretion. When cameras flashed the first pictures of the vessel as it was hauled aboard the deck of a barge on August 8, 2000, two large holes on the starboard side instantly caught the attention of onlookers. To many, here was the smoking gun. True to legend, here was proof that the luckless sub had been hit and fatally damaged by the U.S.S. Canandaigua, the ship that sprang to the rescue of 150 sailors clinging to the wreck of the Hunley’s victim, the U.S.S. Housatonic.

Holes explained

Research led by Maria Jacobsen, head archaeologist on the Hunley project at the Lasch Center, soon proved that the holes occurred long after the Hunley sank and were a product of the twin forces of erosion and corrosion. The Canandaigua was a 1,400-ton war sloop, larger than the Housatonic, powered by sail and a huge, steam-fired screw. “If it had hit the Hunley, it would have cut it in two,” Jacobsen says.

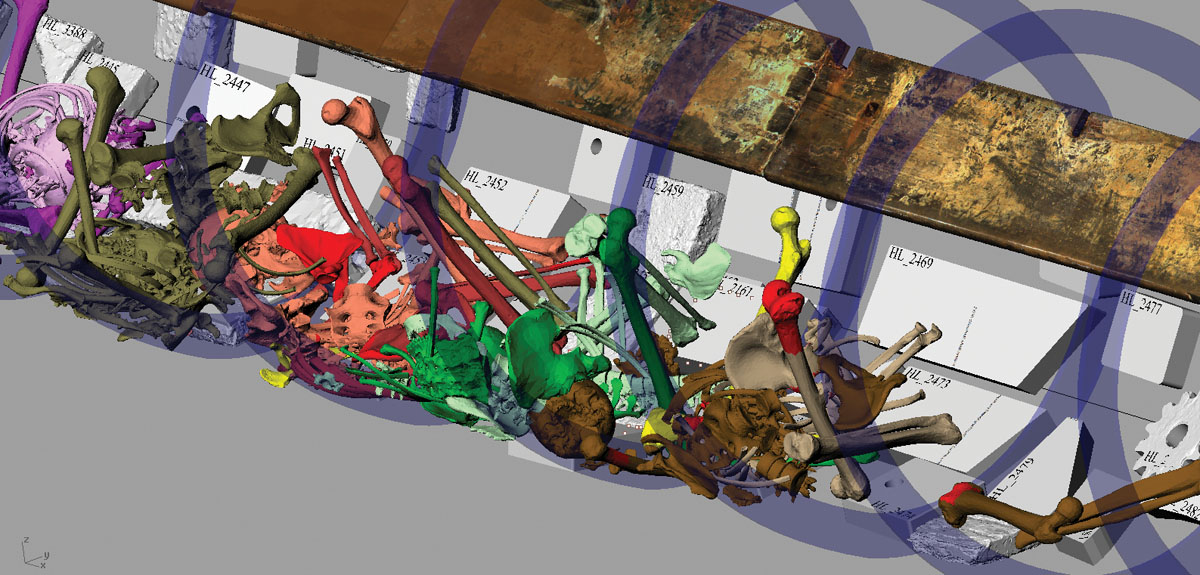

Before they were removed from the sub in 2004, the crew’s skeletal remains were carefully documented with a 3-D scanning device. The digital image above, color-coded by individual, shows the Hunley’s tilted position on the ocean floor, the bench seat higher than the crew’s remains. Iron ballast blocks, shown in pale gray, could be moved to adjust the pitch and trim of the hull. Image courtesy of Friends of the Hunley.

Did small arms fire from the Housatonic play a role? Eyewitness testimony described how panicked soldiers aboard the doomed ship opened up with rifles, pistols, and even shotguns at the Hunley as it approached its prey, illuminated by a near-full moon. (Ironically, at the critical moment of its history, the Hunley abandoned its biggest element of stealth—underwater navigation—and, on orders of commanding Confederate General P.G.T. Beauregard, attacked on the surface.)

At point-blank range, a round from a .58 caliber, black-powder rifled musket—the typical long gun carried by federal troops in 1864—can do a great deal of damage. Did a lucky shot knock a hole in the forward conning tower, or find one of its small viewing ports and thus kill or wound Lt. George Dixon, the Hunley’s skipper?

One of the first examples of damage seen by the divers who found the wreck in 1995 was a softball-sized hole in the forward tower. How it got there is a puzzle. Jacobsen says that it could have been a result of either the explosion that took the Housatonic down or firepower. But no bullets were found in the bottom of the vessel, and the skulls of Dixon and all his comrades showed no telltale signs of bullet wounds.

But the hail of fire from the ship may very well have played a role. Intrigued by the possibility, the Lasch Center team had an exact copy of the forward conning tower cast in iron and subjected it to a field test using period weaponry. The rifles succeeded in cracking it, a finding that may factor into subsequent discoveries when the Hunley’s skin is finally freed from its heavy mantle of encrustation, a process slated to begin later this year.

Shockwaves

Perhaps the most plausible explanation for the Hunley’s demise is that it was too close to the death blow it dealt the Housatonic. Shockwaves from a huge underwater concussion, even without causing lethal structural damage to the Hunley, could have either killed or knocked unconscious her entire crew. After drifting with no power for a few minutes in a choppy sea—and with the forward hatch cover curiously left open—the sub simply filled with water and sank. One hundred thirty-six years later, the sub was found lying less than a thousand feet due east of the Housatonic wreck.

Several findings support this and similar explosion-related theories. For one, none of the surviving drawings of the Hunley give details of exactly how its weapons system worked. Other than it was mounted on a seventeen-foot iron spar bolted to the bottom of the keel at the bow, little is known about the rig. Was the spar simply holding a contact mine, or was it tipped with a barb designed to be driven into a target’s hull, leaving a charge to be detonated at a distance? A reasonable assumption, but so far no proof has turned up to support it.

Legend has it that the charge was attached to a lanyard installed on the Hunley, which ostensibly would play out from a reel, attached to the sub, which would be at a safe distance before tension pulled a trigger. So far, Lasch researchers have found no evidence for such a lanyard reel but remain hopeful that the de-concretion process will turn up something.

No mad scramble

Interestingly, witnesses aboard the Housatonic, testifying in a federal inquest, all agreed on one thing: The explosion occurred when the Hunley was very close to its victim. Exactly how close, no one will likely ever know. The Confederates also left no record of what size black-powder charge they installed on the Hunley that fateful night; undocumented reports give a range of ninety to one hundred and thirty-five pounds. Such a detail would be helpful for computer simulations of the explosion’s impact.

A somber finding associated with the remains of the Hunley’s men is a telling clue about their last moments. Researchers spent months poring through hundreds of bones, scraps of clothing, and personal effects. Instead of being scattered willy-nilly about the vessel, the remains lay in discrete places arranged sequentially along the ship’s crankshaft where the men worked.

“It’s clear that there was no mad scramble for the exits. They all died at their stations,” Jacobsen says. “Whatever happened, it was so fast that they couldn’t move or maybe they were already dead or unconscious.”

Much of what people believed about the Hunley turned out to be flat wrong. And here’s what the team has discovered so far.

Museums throughout the world groan beneath the weight of iron artifacts recovered from the sea.