What kind of leadership will take us to Mars?

by Lauren J. Bryant

Leadership is a hot topic. Type “leadership” into the books search bar on Amazon.com, and you’ll get more than 137,000 results including Lean In: Women, Work, and the Will to Lead by Sheryl Sandberg, the full suite of titles by leadership guru Stephen R. Covey, and even Dale Carnegie’s 1937 classic, How to Win Friends and Influence People: The Only Book You Need to Lead You to Success.

So what’s left to say about leadership? Plenty, if you ask Marissa Shuffler. For one thing, she says, in this age of huge, complex, global systems and organizations, there’s really no such thing as “a” leader.

“It’s very hard to find one person who is very good at all aspects of leadership,” Shuffler says. “In my research, I’m thinking about shared or collective leadership. How do multiple people take on leadership responsibilities? What makes a person likely to step up and take on leadership but also willing to step down and be led?”

Surprisingly, Shuffler started studying shared leadership in perhaps the most top-down organization there is: the military. As a consortium research fellow with the U.S. Army Research Institute from 2004 to 2006, Shuffler worked with her mentor Jay Goodwin, chief of the institute’s Foundational Science Research Unit, to study the army’s leadership process.

It was the post-9/11 period, when the military grappled with frequent deployments and rapid change in a largely unknown environment. The U.S. Army was being forced to transition, Shuffler says, from a “traditional warrior mentality” to a multinational, distributed approach to leading and following.

“The leadership in the United States was trying to direct and provide resources to folks in Afghanistan and Iraq,” she says. “How that direction got interpreted was a big issue. That got me interested in how you prepare leaders and team members for environments that can be so challenging and different.”

Hello…hello?

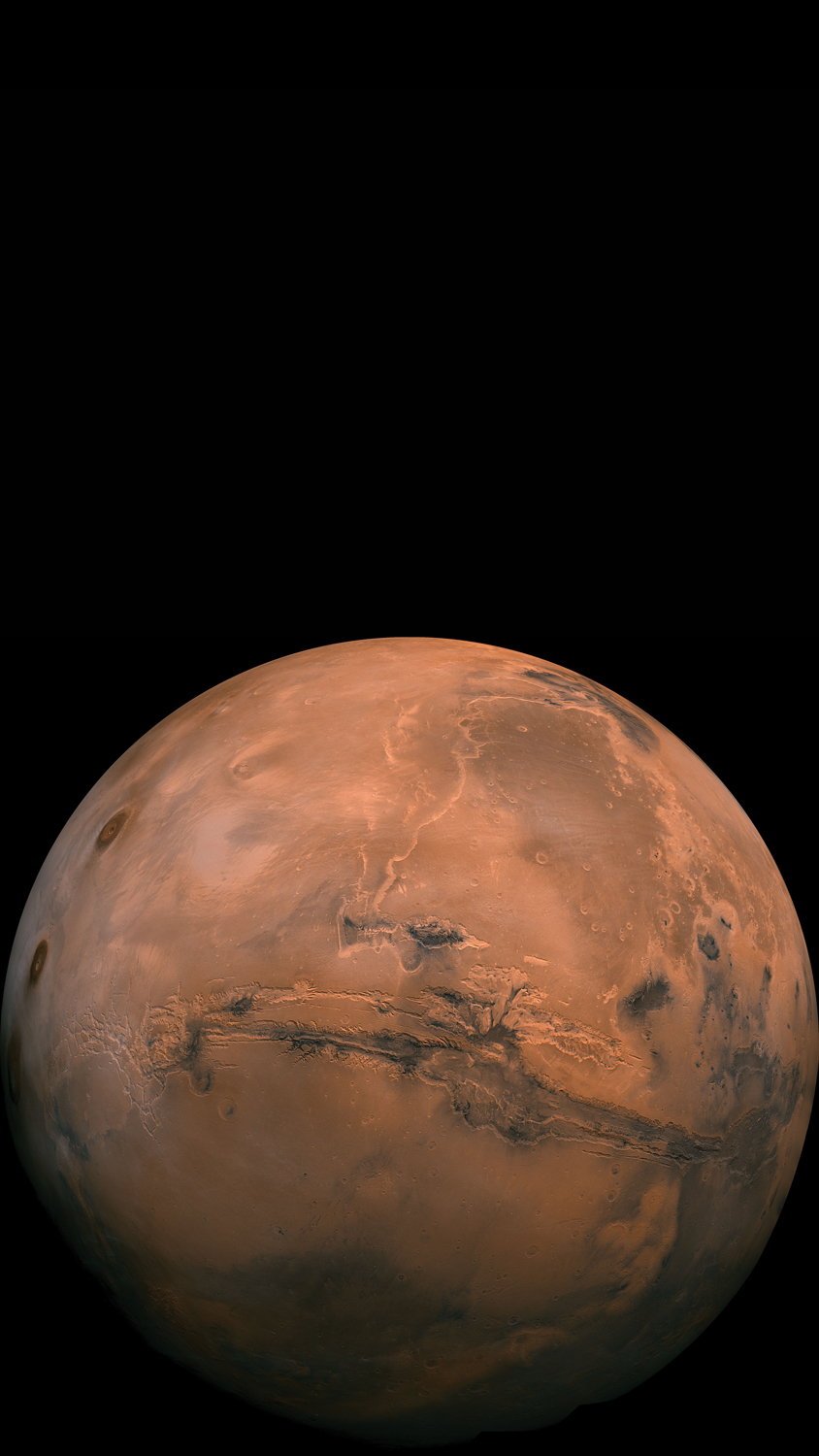

When it comes to challenging and different environments, the winner-take-all has got to be outer space, which is exactly where Shuffler is focusing her current research, along with colleagues from the University of Central Florida (UCF). With a grant from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Shuffler and her colleagues are exploring leadership in the context of long-duration space missions, specifically NASA’s journey to Mars, planned to launch sometime in the 2030s.

Since her work with the U.S. Army Research Institute, Shuffler has developed expertise in the area of “high-risk” leadership—leaders who must function in stressful, demanding environments where errors in judgment can cost lives. Space travel to Mars certainly qualifies. When the human Mars mission launches, four astronauts will be confined together in a space module roughly the size of a large American bedroom for at least eight months. And their isolation will be extreme. The farther they travel from Earth, Shuffler explains, the more tenuous communication with ground control will become.

“On long-duration missions, you go from immediate contact between crew and ground control to looking at a twenty-minute delay each way,” she says. “So there is a forty-minute delay between hellos.”

What happens if a time-sensitive issue must be resolved? What if the situation is something neither the astronauts nor ground control has ever experienced or anticipated? Shuffler is taking a three-pronged approach to helping NASA answer these kinds of questions before the Mars mission leaves the ground.

First, she and her research team members are looking backward. Taking what she calls a “historiometric approach,” Shuffler, her students, and colleagues are analyzing historical examples, such as Arctic explorations, in which teams of people were isolated in harsh environments, cut off from communication. As they explore the historical literature for common themes, ideas, and lessons, “we’re thinking about adaptation and other leadership behaviors,” Shuffler says. “How did the team anticipate or make sense of their situation? How did they decide to take a particular action, to adapt in new and different ways?”

The team is also studying the more recent phenomenon of round-the-world sailboat racing. The focus here is on how groups of people manage together in very confined spaces.

“The Mars mission will be years in total duration, in very small living quarters, so we’re trying to make sure the astronauts don’t kill each other!” Shuffler says with a laugh.

More seriously, Shuffler’s goal is to identify what astronauts and mission teams can do before and during long-duration flight to build teamwork and leadership skills.

The second approach Shuffler is taking is a more controlled investigation. In her Clemson University laboratory and at a UCF lab, undergraduate students are participating in a three-and-a-half hour computer simulation, designed to study how participants handle leadership responsibilities.

Shuffler describes the computer simulation as a “Star Trek-type game” that mimics a space exploration mission during which participants must deal with environmental factors as they carry out duties resembling scientific research and technological tasks. But there are no leadership roles assigned at the outset of the simulation. The intent is to see how, when, and why leadership emerges. Who steps up, and who steps back?

“One of the big things we’re most unsure about with the Mars mission is how leadership will emerge within the NASA crews as they get farther and farther away,” Shuffler says.

Data from the computer simulation experiment are still being collected, but Shuffler ventures some observations based on similar research she did while earning her Ph.D. Trust is a “huge player,” she says. Team members must trust one another to be willing to “put themselves out there” as leaders as well as accept leadership from others. Personality also comes into play, but not in the way you might think. It’s not the “born leaders” with big personalities who emerge successfully, Shuffler notes, but rather, the person who has a strong “social astuteness,” understanding when to step forward and when to follow along.

As a third way of studying leadership in outer space, Shuffler and her research colleagues are taking their work to the field, in this case, the Human Exploration Research Analog (HERA) at the Johnson Space Center in Houston.

HERA is a three-story habitat designed to resemble a space exploration environment as realistically as possible, including “simulation of isolation, confinement, and remote conditions of mission exploration,” according to the HERA information package.

For two weeks at a time, HERA is inhabited by groups of four people whose age, physical characteristics, and educational background closely match that required of actual astronauts. While inside HERA, the subjects follow a strict schedule during which they carry out flight simulations, research tasks, communication with ground control, and maintenance, as well as sleep and exercise.

Meanwhile, researchers such as Shuffler carry out their own series of tasks, manipulating variables such as sleep deprivation and communication failures. HERA has a surveillance video and audio system, and NASA sends out daily updates to researchers. The HERA subjects also fill out surveys after completing their fourteen-day mission, providing what Shuffler calls a “really nice wealth of information.”

The goal of all Shuffler’s NASA-related work—archival research, computer simulation, and the HERA test bed—is to better understand leadership dynamics among teams whose members are a few feet and about 140 million miles apart. With greater insight into what it takes to effectively balance and coordinate leadership in such situations, Shuffler aims to provide NASA with recommendations of measures that can be taken to advance leadership development during existing training on Earth as well as during the actual mission. Although her research is ongoing, Shuffler imagines her recommendations will focus on a combination of selection and training. Astronauts are already a select group of people, of course, but Shuffler hopes to add to the list of characteristics that should be taken into account when they are chosen.

What sort of characteristics? Adaptability tops the list, Shuffler says—someone who has the ability to pick up on social dynamics, understanding when social problems arise and how to address those conflicts so that the team can get along. Essentially, Shuffler says, “you’re looking for people who have a team orientation, who enjoy working with other people. It sounds really straightforward, but you’d be surprised. It’s a big issue.”

Developing conscious leaders

When it comes to leadership environments, you might think a brick-and-mortar health care system anchored in South Carolina would be about as different from outer space as you could get, but you’d be wrong, according to Shuffler.

“Folks in health care aren’t stuck together in a small physical space for what seems like forever,” she says, “but day to day, a lot of folks are making life and death decisions. It has its high-risk component.”

That high-risk component is what brings Shuffler to another of her current research projects, studying leadership development within the Greenville Health System. For the last eight years or so, Shuffler explains, GHS has been developing a “conscious leadership” program among the system’s approximately 3,500 employees. In Shuffler’s words, conscious leadership involves leaders being aware of and attentive to both what is going on in the moment and their own reactions. “It’s about regulating your emotions in order to promote a healthy climate for teamwork and accomplishing tasks at all levels of the organization,” she says.

GHS reached out to Shuffler to assess how well this approach is working and how it might be further developed or expanded. Last fall, Shuffler surveyed about five hundred GHS leaders to measure where they stood with respect to conscious leadership principles such as openness, honesty, and responsibility. This spring, she conducted a survey of GHS employee engagement. Using data from both surveys, she’s now looking for links between leaders’ understanding of conscious leadership principles and employee satisfaction.

What kind of behaviors do leaders exhibit? What does leadership look like for a top manager versus a front-line nursing manager? Those are the kinds of questions Shuffler is exploring, and although she is still analyzing all the survey data, she says, preliminarily, that “there is definitely something going on.

“We’re seeing that leaders who have a better understanding of conscious leadership have employees who are more engaged and committed,” she says. “The question is, what’s driving that? Were they good leaders already, or is it the specific conscious leadership approach?”

Shuffler is setting up focus groups and interviews with GHS leaders at various levels to explore whether and how leaders are applying conscious leadership principles in their everyday work. Already, though, Shuffler is sure of one result.

“Whether it’s NASA or GHS,” she says, “the ability to adapt is huge.”

No ‘i’ in leader

These days, health care environments are constantly changing, from policies to medical procedures to billing processes, and, like outer space, they can be unpredictable, high-demand environments where shared leadership is essential, Shuffler says. She calls it “collective leadership,” pointing out that it’s been around for a long time.

“We’ve been doing it for years and years,” she says. “Look at the top management teams of major organizations. There’s not just one person, but multiple people sharing responsibilities. We see this even in our own everyday work groups, where there may be a formally appointed leader, but someone else steps up.”

Collective leadership centers on leaders who also operate as team members and who pay attention to context. What works in one situation is not going to work in every situation, Shuffler notes, and the leader who assumes she or he can just do the same thing all the time won’t succeed. On the other hand, successfully sharing leadership has strong positive effects on performance and outcomes, Shuffler says.

So why is it that so many teams function badly?

Because we’re not paying attention. Too often, that “works well with others” line on a résumé just isn’t true. A team may be together, Shuffler says, but “focused on jumping in and getting busy on the task.” Instead, “we need to figure out how to work together as a team first. Who knows what? How are we going to share that information? What’s the best way to communicate?”

To build a team this way takes time and sensitivity, Shuffler says, especially in the 21st century, when so many teams are virtual, united only through emails and videoconference screens. Building trust with such virtual teams is distinctly challenging, a reality that Shuffler focuses on during her “Teamwork in the 21st Century” course.

During the course, Clemson students participate on virtual teams with students from other universities. Shuffler notes that most students find it a “very eye-opening experience” to “feel like a team” without depersonalizing remote team members or blaming them when something goes wrong. It’s not always a smooth process, but Shuffler says, “I’d rather they learn about that here in the classroom so that their first time dealing with virtual teamwork isn’t on the job.”

As steeped as she is in the complexities of leadership qualities, good and bad, it could be hard for Shuffler to identify someone she thinks of as a great leader. When asked that question, however, she has a ready reply.

“Honestly, I would say my dad. He’s an engineer, and I spent a summer working for him prior to starting graduate school. Engineers aren’t typically known for their social skills but my dad is very adept, keeping people in the office engaged, showing care and concern, but also keeping everyone on task and moving forward. I definitely admire his leadership.”

Marissa Shuffler: Shared leadership improves success when the challenge is technically complex. Photo by Patrick Wright.

Marissa Shuffler: Shared leadership improves success when the challenge is technically complex. Photo by Patrick Wright.Marissa Shuffler is an assistant professor of industrial and organizational psychology in the College of Business and Behavioral Science. Lauren J. Bryant is a writer in Bloomington, Indiana.