Making Magic

by Frank Stephenson

Trouble in Magic Land

Today’s VFX industry is like the weather. If you don’t like it, wait five minutes; it will change.

Not that the movie-going public worries about such things, but the industry that puts the razzle-dazzle visual-effects magic into their favorite films is in gut-wrenching turmoil worthy of a scene culled from the Iron Man series.

Nothing illustrates the problems vexing the VFX industry better than the news surrounding the blockbuster hit Life of Pi. On the eve of the film’s being tapped for an Oscar for Best Visual Effects in February, the company that did most of the VFX heavy lifting on the project, the twenty-six-year-old Los Angeles firm Rhythm & Hues, filed for bankruptcy. The move instantly put more than two hundred and fifty employees—many of whom reportedly had spent a year or more working on Pi—out of a job.

Jerry Tessendorf came to Clemson from Rhythm & Hues Studio, where he served as chief graphics scientist. In 2008, he was handed the Academy Award’s Technical Achievement Award for his water-simulation software, an outgrowth of his research in fluid dynamics at Brown University (Ph.D. 1984). His techniques have been applied to almost every major motion picture involving water since around 2000, including Titanic, Waterworld, and, most recently, Twentieth Century Fox’s megahit, Life of Pi.

Subsidies steer the trade

The demise of Tessendorf’s old company typifies the recent upheaval in an industry that once seemed rock steady with an annual growth rate projected at 8 percent. Spawned in the United States in the 1970s by a handful of private companies that contracted their highly specialized services to Hollywood moviemakers, the industry is now reeling from global competition and a chase for subsidies that boost studio profits, Tessendorf says.

At the moment, the lion’s share of work goes to locations with large tax subsidies for film production, primarily London, Vancouver, New Zealand, Sydney, and Montreal, Tessendorf says. “There has also been a small ‘boomlet’ of work in New Orleans and Atlanta from state-sponsored subsidies in Louisiana and Georgia. But North Carolina, which just terminated its subsidies, will see a dramatic downturn in work this year because TV and film productions promptly moved out to freshly subsidized locations.”

Because subsidies in California are insignificant, Tessendorf says, the trend has devastated VFX companies and people in Los Angeles and San Francisco. But overall, demand for VFX work in the film industry continues to grow, Tessendorf says, as does the amount spent on it.

The impact of globalization has led to increasingly loud protests by workers within the U.S. industry over the issue of unionization. Among the wide array of enterprises that support the Hollywood movie machinery, the VFX industry is conspicuous for being the only one not represented by a union, a situation that union-boosters say leaves VFX employees defenseless against the pressures wrought by a suddenly vicious global marketplace.

“We may continue to see large companies break up into smaller ones; at least that’s what we’re seeing at the moment,” Tessendorf says.

Tessendorf’s biggest worry is over what the tumult means for his students. His most recent graduates face the most challenging job market in the program’s fourteen-year history.

“When there were a clutch of fairly stable companies, students could expect to get work fairly regularly in Los Angeles or San Francisco,” he says. “Now, with many of those [companies] in bankruptcy or moving their work out of the country, we need to find ways to grow relationships with those new companies.”

Fractal flames

Even the Clemson program’s “star” students have felt the pressure. Yujie (pronounced “you-jay”) Shu, an international student from southern China, graduated in August. Her master’s thesis— which focused on an intriguing bit of cyber-chicanery known as fractal flame wisps (essentially clever algorithms that give life to computer animations such as the delicate 3-D “genies” seen buzzing around in Brave, the 2012 Pixar animated hit)—helped her catch Hollywood’s eye in 2012. Shu was one of only two students in the country tapped for the coveted internships offered by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. She spent three exhilarating months working as a card-carrying technical staffer for Industrial Light & Magic in San Francisco.

“This is a bad year for film production,” Shu says. “Lots of people in the [VFX] industry are being laid off, and there’s not a lot of choices left like there once was. But there are jobs out there—it just takes more work to find them.”

Shu was hired several months before she graduated, something she says is “not uncommon” for DPA seniors. NVIDIA, a Santa Clara, California-based company that develops a top line of computer graphics cards—literally the engines that drive the entire VFX industry—hired Shu online without so much as an interview. Shu says the job will help her “stay relevant” for eventual work in film production, her career goal.

Meanwhile, Tessendorf is optimistic that the present upheaval in the industry will soon level out.

“We definitely have a problem, but I believe it’s one the market may solve,” he says. “In six more months the picture could be very different. The chaos that’s going on now could be largely resolved by then, because this industry moves so very, very fast.”

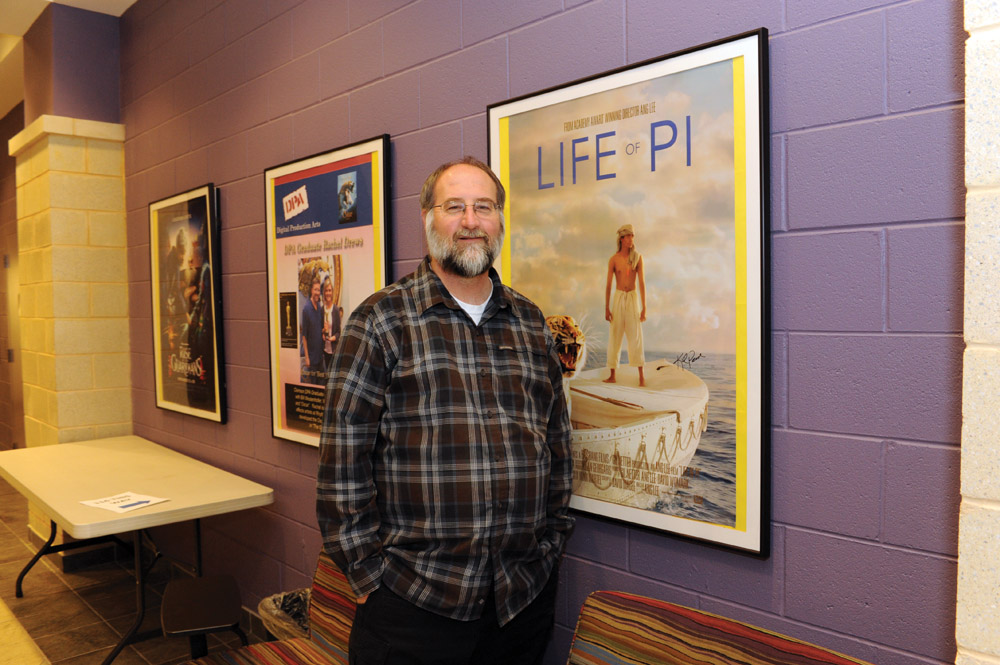

Jerry Tessendorf, whose water-simulation software helped Life of Pi win the Oscar for Best Visual Effects, asks students to produce pro-quality work. Photo by Patrick Wright.

Robert Geist, cofounder of Clemson’s Digital Production Arts Program, is also known as a pioneer in the field. His most recent contributions include work on The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey. Photo by Craig Mahaffey.

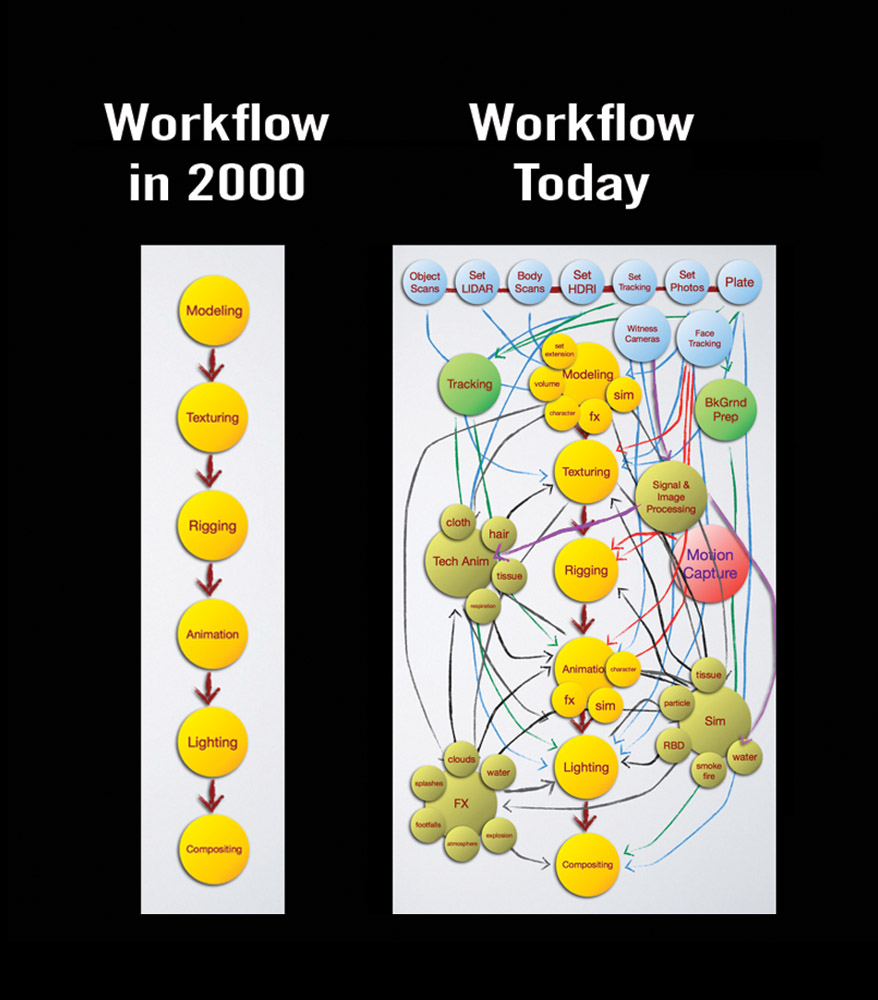

Today’s digital production demands enormous computing power. The PDA program can access 600,000 computing cores, dwarfing most mainframes.

For today’s blockbusters, the real wizards work their magic behind the scenes, with computers.

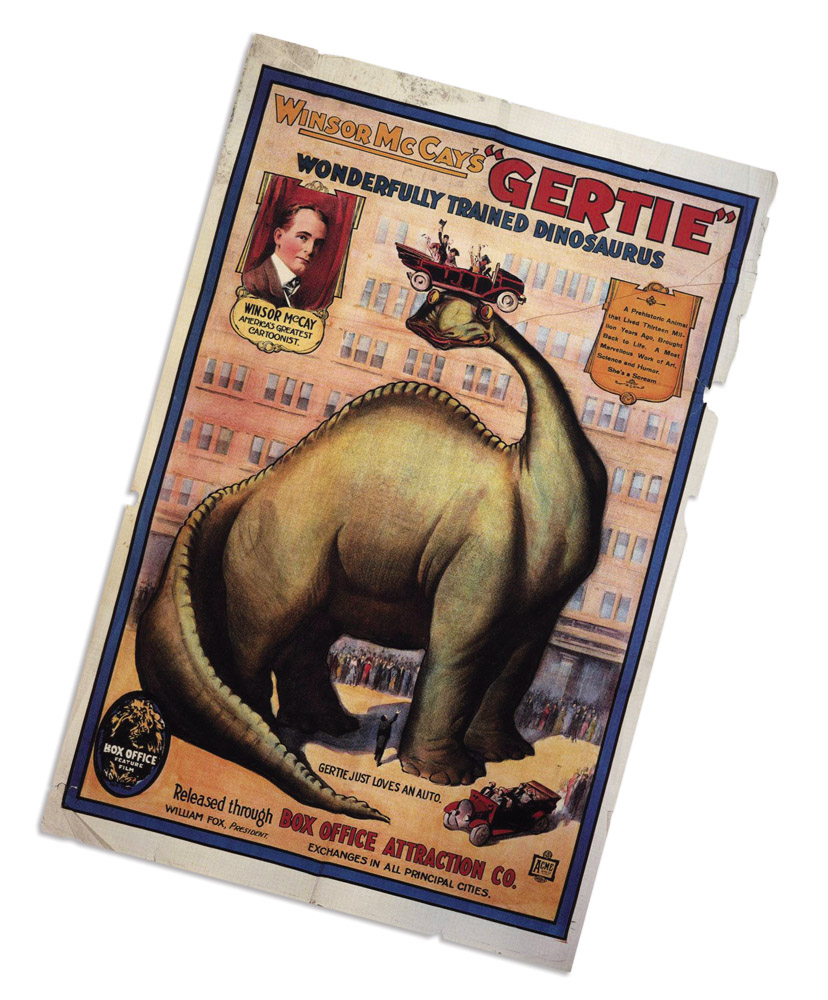

Film buffs, take note: We’ve evolved eons since Gertie the Dinosaur. In 1914, moviegoers thrilled to the silent antics of Gertie, an animated dinosaur drawn by New York comic strip artist Windsor McCay. A young film industry would never be the same.

Today, animation and special effects, fused to a good story line, are the driving force behind cinematic entertainment and advertising the world over. From Hollywood blockbusters to TV commercials and even digital billboards, the unmistakable stamp of animators, computer graphics specialists, and a host of other techno-wizards is in-your-face ubiquitous. And we love it. Of the fifty top-grossing films of all time, all but seven relied on special effects or visual effects, the field’s latest, computer-age incarnation.

In the past forty years, the business of special and visual effects has exploded, ignited by sparks of creative genius that gave the world such sci-fi hits as George Lucas’s Star Wars (1977) and Steven Spielberg’s Jurassic Park (1993). The business itself has morphed from a handful of small private companies in the United States to an international economic titan, now boasting major centers in Canada, Europe, Japan, Australia, and India.

Pioneering companies such as Industrial Light & Magic, Pixar, and DreamWorks today comprise just the iceberg-tip of an industry that employs thousands on almost every continent. Thanks to globalization, lightning-fast changes in technology, and widespread economic malaise, all these competing companies are obliged to work harder, faster, and smarter to survive. This means that, as never before, movie moguls around the world need fresh supplies of young—and increasingly adaptable—talent in every phase of digital production.

Traditionally, the top source of such talent has been campus-based art programs that offer special training in various aspects of computer graphics. While that’s still largely the case today, there are a few highly specialized programs scattered around U.S. campuses that follow a different tack. These programs intentionally draw from a variety of disciplines to produce graduates ideally suited for working not just in the entertainment or advertising arenas but also in science, medicine, engineering, and a host of other fields increasingly hungry for talent in visual effects.

Of art and science

“There’s good evidence that we’re one of the top programs in the country.”

It’s no idle boast that Clemson’s Robert Geist drops on an interviewer. He’s the cofounder (with Sam Wang, now a retired professor from Clemson’s art department) of the university’s Digital Production Arts (DPA) program, now into its fourteenth year.

When he and Wang set out to build the program in the late 1990s, they recognized a program run by Texas A&M as the undisputed lead horse in providing the kind of academic training in digital production they envisioned for Clemson. For five years now, the guy who started the A&M program, Donald H. House, has kept an office around the corner from Geist’s. A pioneer in computer visualization techniques, House is one of eleven full-time faculty members in the Clemson program. He is also the program’s current director.

“We’re a magnet for [industry] recruiters who come through all the time,” Geist adds. “This past summer, DreamWorks held— at their own expense—an intensive, ten-week training program here. They plan to repeat, and other studios plan to do the same. Our students are frequently tapped for major honors.”

Just last year, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences picked two students in the country for lucrative summer internships in Hollywood. One was from Carnegie Mellon; the other was second-year Clemson DPA student Yujie Shu. The year before that, two of the five students picked by a national search to work on a DreamWorks special project were from Clemson. Marc Bryant, a 2003 DPA graduate, just won a Visual Effects Society Award for Outstanding FX and Simulation Animation in an Animated Feature Motion Picture for his work on the movie Frozen: Elsa’s Blizzard.

Since the program awarded its first master’s degree in fine arts in 2001, names of its alumni have run in the credits of more than 130 feature films industry wide, Geist says. “Frankly, it’s gotten to the point now that it’s sort of rare not to see some of our graduates listed in the credits of any major picture these days.”

And then there’s the program’s leadership. In 2010, the program attracted Academy Award-winner and Ph.D. physicist Jerry Tessendorf, head graphics scientist at the California-based Rhythm & Hues Studio. Both Tessendorf and Geist have grabbed headlines for their contributions to Hollywood—Tessendorf’s water-simulation software helped Life of Pi win the Oscar for Best Visual Effects, and Geist’s digital map-filtering techniques on The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey helped make that film a runner-up for the same award in the Academy Awards presentation in March, 2013.

Geist is quick to put DPA’s rapid ascent into perspective. “When you’re talking about being a top program, you have to realize that there’s just not many programs of this kind to start with. We’re small—only thirty-five students enrolled in the spring semester—and we’re highly selective.”

Training in the magic arts

What motivated Geist and Wang to start the program was their growing realization in the early 1990s that the visual effects industry—known in the trades as VFX—was on a limitless trajectory with boundless potential for growth and innovation, thanks largely to vast increases in the power of computers. Star Wars had wowed audiences by pushing a young field known as CGI (computer graphic imaging) to dazzling light-saber levels audiences had never seen.

But the machines that created those images were kids’ toys by the time Geist and Wang sat down for their first serious chat. The two saw a need to formalize an academic bridge between Geist’s specialty, computer graphics (Ph.D. in mathematics, Notre Dame, 1974), and Wang’s, photography with an emphasis on digital art. Both disciplines faced a palette of technical and artistic power that seemed to grow exponentially by the day.

The many talks Geist had with friends in the VFX industry helped him and Wang formulate both a practical curriculum and a philosophy for starting a program for Clemson. Today’s program still reflects those early ideas, Geist says. “Essentially, we’re all about matching our graduates with exactly what the industry needs at any given time. Since this is a rapidly changing field, that’s a real challenge.”

While housed within Clemson’s School of Computing, the DPA is jointly administered by the university’s Department of Art. The terminal degree is a MFA, theoretically attainable in two years. But most students usually require three because of the program’s stringent requirements, Geist says.

“To get accepted into the program, students have to demonstrate both a knowledge of and a competency in both computing and art. We basically want people who are both artists and computer scientists at the same time. We want balance, though.”

Students don’t need to be superb freehand artists, for example, to qualify for admission. Their art talents can be oriented to music, sculpture, photography, or even art history. In the past, DPA students have come in with backgrounds in architecture, engineering, and a variety of science disciplines. But by the time they graduate, the one, irrefutable common denominator is a fundamental grasp of writing computer code, literally the coin of the VFX realm.

“It’s common for some of our students to come in with computer skills that need polishing. We have remedial coursework for that as well as in art, which is why for most students the program takes three years to finish.”

Geist says that his contacts in industry—which he works vigilantly to maintain—tell him emphatically the kind of graduates they’re looking to hire. “They want people who can pick up a pen and sketch out a storyboard and then put that down and knock out a shell [computer] script and not even pause in between.”

Accordingly, the program is built around a no-nonsense curriculum that for this past year has featured a rare component—a ten-week summer “boot camp” run by one of Hollywood’s most famous VFX companies, DreamWorks. Though the program is an optional extension of core coursework, it’s highly popular because students know that it offers them the closest encounter with the real VFX world that they’ll ever have on a college campus.

Hollywood boot camp

Robert Helms enjoys a perspective on Clemson’s DPA program known to few. A Clemson native, Helms is a 2003 graduate of the program, and, after ten years of steady work in the industry, his ties with his alma mater are closer than ever. For the past few summers, his employer, DreamWorks, has sent him back to Clemson to help run a session of an outreach project directed at select academic programs around the country. At Clemson, it’s essentially a highly intensive, ten-week course tacked onto the spring semester. Clemson is one of the few campuses that DreamWorks collaborates with as a means of creating a direct pipeline between the company and the best sources of talent in the country.

A specialist in digital character animation, Helms was hired straight out of the DPA program in ’03 by California’s Rhythm & Hues Studio, which is now defunct. After three years there, he worked for a London-based company for two years before coming back to California to sign on with DreamWorks—“jumping around,” he says, is the rule in a young, fluid industry that of late is more fluid than ever.

Helms has seen huge changes both in the VFX industry and within Clemson’s digital arts program. DreamWorks, although buffeted by the same market upheavals that now rock the whole industry, likes what it sees at Clemson and is happy to keep investing in it, Helms says.

“Clemson has been turning out students that DreamWorks and other high-end companies have been interested in for some time now,” he says. “This costs DreamWorks, so they’re very careful about who they do this for.”

Students who sign up for the optional program can expect to work up to eighty hours a week on start-to-finish film projects, Helms says. “It’s full production, from developing story boards to building props, animating characters, setting up the lighting, learning how the camera works, doing the [computer] rendering, and putting it all together.”

Students emerge from the project with yet another “demo reel” and all the computer work behind it for their all-important portfolios, literally their only tickets for good jobs in the industry. Helms says that he’s constantly amazed at the quality of what he sees. He believes that much of the credit must go to his alma mater for amassing a technical base that far surpasses anything he saw during his student days.

“What they have here today compares favorably with an industrial setting,” he says. “They started out on a shoestring with only a couple of math classrooms and maybe a dozen or so computers. Now, even though they still don’t have a huge budget, it’s pretty close to what you’d see in the industry.”

The program now boasts a $6 million phalanx of computer hardware that includes more than 600,000 computing cores that share the industry-standard Linux programming language. The system’s speed, which dwarfs that of most mainframe computer-based centers, gives students the power necessary to process the enormous volumes of data that standard, industrial-grade CGI production typically demands. Only a minute or so of a finished CGI film can easily consume a thousand or more hours of computer processing, even with the fastest machines and software available.

The program’s professional look and feel benefits from a new screening studio featuring exactly the same kind of cinema-grade projection system that has helped numerous projects win top technical awards in Hollywood. The system gives students a critical tool for studying their digital creations in fine detail on a daily basis.

Helms is only one of several DreamWorks specialists who come to campus each year to help with the outreach program. The program’s California-based supervisor, Grazia Como, describes it as “a mutually beneficial talent search.” Normally, she says, DreamWorks averages hiring thirty or so top students from around the country each year.

“Clemson’s got a great program. We’ve collaborated with them for a long time and look forward to continuing the relationship,” she says.

The future of magic

Students interested in pursuing careers in the VFX industry—particularly those with aspirations to work in film—are under no illusion about what drives their chosen field. Since the days of Gertie, the central goal of special and visual effects artists and technicians has been the same—to cinematically make the impossible possible.

Until the advent of powerful computers in the late 1970s, the bag of tools and tricks available to Hollywood’s elite corps of special effects gurus held few options. The unreal was made “real” using a variety of camera techniques such as multiple exposures, rear projection, mirrors, and a host of mechanical, sleight-of-hand tricks that could be pulled off on a live-action set full of the right props. Instead of Faye Wray, the real star of the first King Kong film (1933) was a clay model of an over-sized gorilla that enjoyed climbing skyscrapers, all thanks to painstaking stop-action photography.

When computers eventually made it possible to create moving images entirely without cameras, the visual effects industry came into its own. Today, moviegoers not only expect ever-more eye-popping examples of the impossible made not only possible but believable, they demand it. This raises the question—is there any limit to what VFX wizards can do?

For nearly three decades, Robert Geist has witnessed the VFX revolution both as an award-winning educator and as a contributor to the industry. He says that the “Holy Grail” of VFX technology is still well beyond reach of even the brightest, most creative minds out there.

“There’s an old joke in the VFX industry,” he says. “Question: How do you know when you’ve been working in the VFX industry too long? Answer: When you’re walking through a forest on a beautiful spring day, the sun is shining, there’s a gentle breeze blowing, the birds are singing, and all you can do is look around, shake your head, and say, ‘I’ll never be able to render this in real-time.’”

Geist is referring to the capability of using computers to make photo-quality, feature-length films that are all but impossible to distinguish from those shot—and immediately projected or broadcast—with a camera.

“Photo-realistic, real-time rendering is possible for restricted shots, but in general it remains far out of reach. VFX companies today are delighted when they can reduce computation time to less than three hundred hours for each second of the movie they’re making.”

Whatever’s ahead for the VFX industry is riding on the same train that brought it from a fuzzy dream only thirty-odd years ago to where it is today—ever-faster computers and better software, he says. “VFX companies don’t run out of cool ideas; they just run out of time.”

Jerry Tessendorf is professor in the Digital Production Arts Program, and Robert M. Geist III is a professor and currently interim director of the School of Computing; both are in the School of Computing, College of Engineering and Science. Frank Stephenson is a freelance writer who lives in Tallahassee, Florida.

Learn more about Digital Production Arts Program.