El Purgatorio

story by Jemma Everyhope-Roser

photos by Melissa Vogel

In the desolate terrain of coastal Peru, archeologists unearth clues to a culture of artisans and urban prosperity.

El Purgatorio. It’s a name that sounds too poetic to be true. But it’s the name of the largest city in a civilization that lasted for over six centuries, a civilization whose very name has been lost to time. Melissa Vogel, an archaeologist at Clemson University, is set on digging up the truth.

“Our understanding of this civilization, our investigation, is really in its infancy,” she says. So little is known about the people who lived in this city that almost any discovery she makes is a contribution to her field. She explains, “It was already a known site, but the only work done on it previously was by a grad student in the fifties. It hasn’t really been investigated at all, which I found shocking, and after seven seasons of patient mapping and excavations, we’ve learned so much more.”

Today, archaeologists call the people who lived in El Purgatorio the Casma, named after the Casma valley where the civilization flourished. The Casma came into prominence around 700 AD, when their powerful neighbors, the Moche, collapsed in part because of a series of environmental catastrophes brought on by El Niño events.

“If I can speculate a little,” Vogel says, “it looks like that, while the area was dominated by the Moche, the Casma valley was very sparsely populated. Probably, there were people living there at that point who’d managed to keep the Moche out, people who had a fierce, local culture and they just took advantage when the Moche fell apart to reassert their independence and take control over their lives. That’s what I see happening.”

A city of elites

According to Vogel’s radiocarbon dating, the entire city was inhabited contemporaneously, which means it’s exactly as big as it looks. It’s hard to estimate the population estimate without knowing more about family structure, but one of Vogel’s grad students worked up a conservative estimate, at 40,000. That number would make El Purgatorio the largest city in the Casma region but not necessarily the capital, Vogel says.

“The way I’ve looked at it so far is that it was probably a confederacy of elite leaders from various valleys that all held some kind of allegiance and shared culture,” Vogel says. “Perhaps they would have unified against external threats, but El Purgatorio’s elite weren’t the kings and queens of the Casma.”Unlike other cultures, such as the Chimú, the Casma don’t appear to have been centrally organized with all roads leading like spokes into a single hub. Vogel says that’s why she currently calls the Casma a “polity” rather than a state or empire.

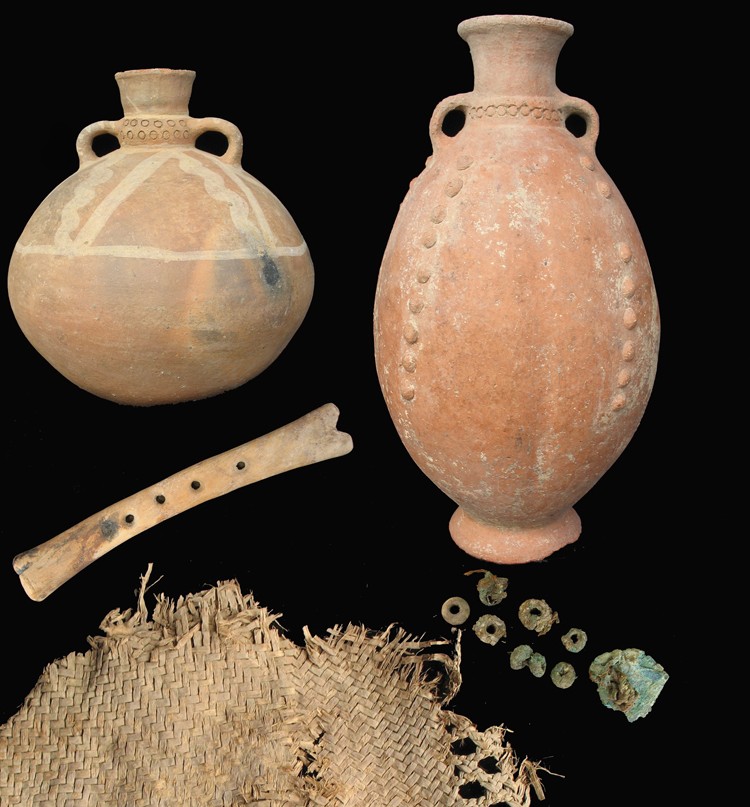

When carefully sifting through the rough sands at the archeological site, Vogel discovered that El Purgatorio seemed primarily a city of artisans, religious personnel, and administrators. Beautifully preserved adobe friezes are still adorned with yellow, orange, red, blue, black, and white paint. A ceramic workshop hints at pottery mass production. Rows of grinding stones for maize imply central food processing, and ceramic vessels, used to store maize beer, show the presence of brewing. Spindle-whorls and other weaving implements indicate that textiles were produced here.

“A lot of what was lost and what we’d love to know about involves cloth,” she says. “In the pre-Columbian Andes, textiles were like currency,.”

Quipus were a series of knotted strings, with different knot types, spacing between knots, and different colors of yarn. The Casma may have used quipus as the Chimú and the Inca did, as a kind of accounting device, but none have been found.

Vogel discovered a very few pieces with ornamental yarn, but as she says, “When folks abandon a city, they don’t leave their blankets or clothes behind.”

The cloth that was left behind seems to have been mostly cotton, which Vogel found surprising, because she had expected stronger evidence for llamas. She had thought, going into the research, that there would be more evidence of trade with the highlands, and alpaca or llama wool would have provided a very material link. “So far it doesn’t appear to be as much of a trading center with the highlands as I expected,” she says, “although they did seem to be taking advantage of opening trade routes.” So far, she has some evidence of trade ranging up and down the coast of Peru and into Ecuador.

Intact burials, unbroken artifacts

Usually, when textiles are found at a site, it’s in a burial, but the Casma buried their dead in plain shrouds. Vogel found thirty-three intact burials and twenty more that were incomplete, as looters had dug through them and scattered the bones.

Even without gloriously embroidered shrouds, the burial sites still have a lot to offer—it’s not only the bones that whisper old stories, but the ceramic vessels buried with them, unshattered. Vogel says the imagery on some vessels hints at complimentary male and female agricultural deities and goes on to describe a maize goddess with delicate feline features. Other jars, called “face neck jars” because they have faces on—you guessed it—the jar’s neck, seem to depict individuals or occupations. But, Vogel says, they’re probably not portraits of the deceased. Some jars drew on natural imagery: felines, octopuses, fish, lizards, turtles, and butterflies.“What we’re working on right now is trying to source our ceramics,” Vogel says, “testing the compositions of the clays to see if they were imported from elsewhere.”

Other goods, such as the copper beads and tools found on the site, cannot be sourced at all, because unlike silver, copper displays a surprising amount of variation even within a single mine. But overall, the city looks to have been a place of urban prosperity.

Since the burials show a relatively healthy population, Vogel believes that poorer people may have lived closer to their workplaces, either on the coast on the farms. As there is virtually no rainfall, farmers would have had to rely on the intricate system of canals for irrigation. Seashells discarded in kitchen middens indicate that seafood would have been packed up seven miles from the nearest coastal fishing villages.

The differences in architecture, the lack of malnutrition found in bones on site, and the manner in which farmers and fishermen seemed to have supported skilled artisans producing specialized goods, seems to point toward a stratified class system. Vogel explains that this would not be unprecedented: “Coastal peoples, such as the Chimú, have a mythology as to the origin of the elite and commoner classes, that they were actually born of different stars, that there were celestial origins for class divisions, and that’s pretty immutable.”

The Casma’s complex culture all but ended when the Chimú, a centrally organized and imperialistic culture, conquered them around 1350 AD. Vogel believes that the Chimú allowed for a “negotiated surrender,” as she found evidence during her graduate work at a more northerly site that the Casma were permitted to ritually “close” their places of worship before leaving; they also did this at El Purgatorio. She assumes that the urban people probably, in her words, “high-tailed it to the hills,” while the farmers and fishermen continued life relatively uninterrupted. She says, “Usually with farmers and fisherfolk, the only thing that changes for them is who they’re paying taxes to.”

The Chimú set up their own regional center along what is now the Pan-American Highway and was at that time a main trade route, and by the 1400s, El Purgatorio had been all but abandoned. Shortly after that, relatively speaking, the Chimú were conquered by the Inca and the Inca by the Spanish, and the rest is, as they say, history.

Rejecting human sacrifice

Vogel is trying to figure out, exactly, what role the little-known Casma played in history’s greater scheme. One of the reasons El Purgatorio has not been thoroughly investigated is that archaeologists have thought of the period when the Casma gain prominence as a period of change and instability in pre-Columbian history. So far there have been no royal tombs, glowing with treasures and gold, no intricately shriveled mummies, no exceptionally artful pottery, no extreme centralization. Vogel hopes that, since the tombs of the elite do not seem to be obvious, she’ll manage to get there before the looters do. She wonders aloud, “Where did they bury their rulers?”

Melissa Vogel cleans a burial in Compound A3. After careful excavation, the project osteologist, Susan Mowery, will analyze the bones, gently pack them, and place them in the Sechin Museum, the location designated by Peru’s National Institute of Culture.

To put this in context, we have to return to their warlike predecessors. The Moche had a culture of conquest and ritualized warfare; their warrior-heroes would capture the warriors of other nations and sacrifice them upon truncated pyramid altars in a ritual that was both gory and public. The religion surrounding selective human sacrifice would have inspired fear and obedience, and it would have also been entertainment for the masses.

Vogel likens this to Roman gladiatorial spectacles in the coliseum.

In contrast, the Casma’s religious mounds were significantly smaller and within enclosed compounds. Right now, there’s no evidence that the Casma practiced human sacrifice in these compounds, although there may be some evidence for dedicatory burials. Individuals may have been buried in the foundations before certain public buildings were constructed, but it is unknown whether this was done to bless the building or whether it was done by families wanting their dead closer.

As a people, the Casma seem to have instead focused on ritual feasting and intoxication, with large segments of the urban population making huge quantities of the fermented corn beer, chicha.

The Casma built high walls around their religious compounds. The walls, preserved in the arid coast desert of Peru, were clearly not used for defense but would have kept people from easily seeing or hearing what was going on inside. The restricted access to rituals, and the control of access to religion by the elite, is the Casma’s legacy. The Chimú, who eventually went to conquer the Casma around 1350 AD, built even grander versions of these compounds.

“The phrase I’m dancing around using to describe this,” Vogel says cautiously, “but has been proposed in the past, is ‘the secularization of state.’”

The Moche were more theocratic and the Chimú more bureaucratic. Learning about the Casma may help Vogel understand that transition and the Casma’s place in history.

Vogel says that, most of all, she wants people to understand that they were a major culture at this time. Its true name may be forgotten, but we can still learn about who these people were and how they lived. Or, as Vogel says simply, “I want you to know that these people existed.”

Melissa Vogel is an associate professor in the Department of Sociology and Anthropology in the College of Business and Behavioral Science. Her work is funded by the National Science Foundation, the Brennan Foundation, and Clemson University. You can learn more about her project at her project at her website, Project El Purgatorio.

Jemma Everyhope-Roser is the assistant editor at Glimpse.