restoring Hunnicutt

by Jemma Everyhope-Roser

During the summer of 2013, the project formed a new channel and laid erosion-control matting on the banks. Photo courtesy of the Hunnicutt Creek Project.

During the summer of 2013, the project formed a new channel and laid erosion-control matting on the banks. Photo courtesy of the Hunnicutt Creek Project.

As a campus stream gets new life, student researchers check its vitals.

The project to restore Hunnicutt Creek will take this stream back to a better time.

Previously carved into a straight ditch for agricultural drainage, Hunnicutt Creek’s rivulets run through Clemson’s south campus and pour through the botanical gardens, meeting near the Walker Golf Course and draining into Lake Hartwell. To mitigate the construction of a nearby chain grocery store, a project was undertaken on the Clemson University main campus to restore three hundred feet of stream and three acres of wetland. Three campus faculty members received funding to monitor and assess physical, chemical, and biological changes in response to these restoration efforts.

That may not seem like much—until you know the workload that goes into restoring an actively flowing stream system.

Don Hagan, Jeremy Pike, and Cal Sawyer head the effort—and the student-driven Creative Inquiry projects associated with it. The project has been going on for three semesters, and this past semester, fifteen students in a Creative Inquiry project got the chance to dirty their boots in the name of science. Balancing the students’ strengths, needs, and interests, the three faculty members divided the undergrads into two teams that would test restoration methods: vegetation and stream.

The vegetation team, focusing on removing the invasive species, particularly Chinese privet and silverthorn, established thirty plots, namely reference plots featuring the ideal landscape, control plots overrun by invasives, and the plots for each method being tested. The students set aside control plots overrun with invasives and then, leading teams of community volunteers, experimented with removing the plants via chemical control, mechanical means (pulling weeds), a mechanical-chemical combo, and goats.

Yes, goats.

“We got the goats from Wells Farms, in North Carolina. We had forty goats. It was fun,” Pike says.

To measure the methods’ effectiveness, the students have been taking stock through stem counts of plant species, and by using the Carolina Vegetative Survey method to determine vegetative coverage.

How did it all turn out?

Gary Pence, a senior who has the opportunity—unprecedented, for a undergraduate—to present his original restoration research at a conference in Chapel Hill, tells me: “We’re still collecting data to understand how well these methods worked over extended periods of time.”

As of right now, the mechanical-chemical combo wins out. The method, which involves removing invasive plants by hand and selectively painting the cut stalks with a root-killing herbicide, is labor intensive but effective. Although the goats ate their way through some particularly dense thickets, Pence says, “They were not selective at all. They eat a lot of the plants we don’t want them to eat. They like our little maple saplings. Those taste really good to them, so they would eat them all up first.” The goats also enjoyed munching the Chinese privet, but the silverthorn? Not so much.

Hagan, describing some of these plots as “impenetrable,” says, “What the goats did was open it up. They nibble off the branches and the leaves. And they made it much easier for our students and groups of volunteers to come in afterwards with follow-up strategies for eliminating those plants.”

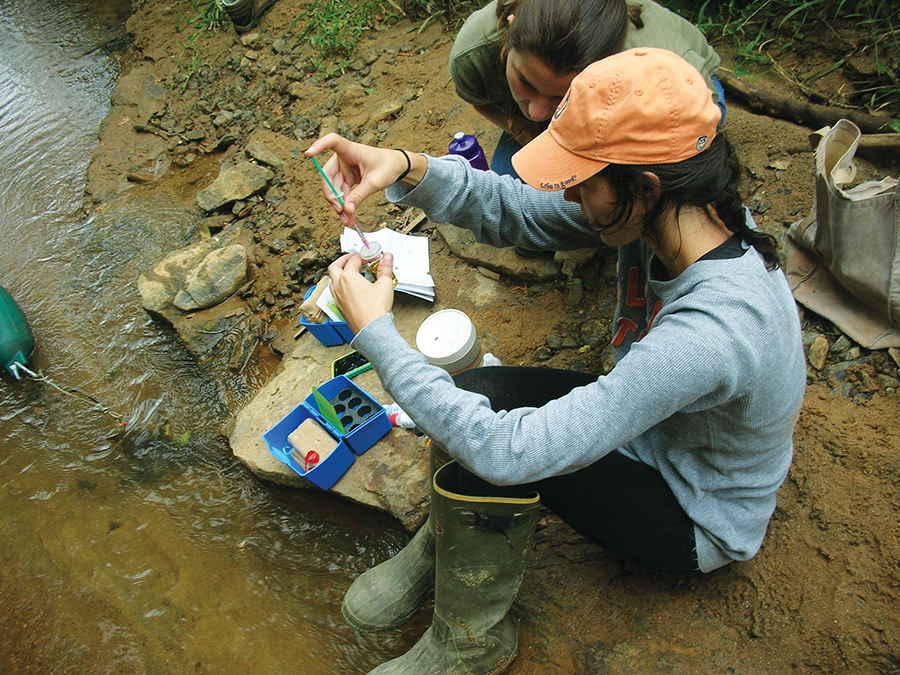

Student researchers Nicole Harper (with the hat) and Carolyn Lanza sample water quality in the restored habitat. Photo by Jeremy Pike.

Student researchers Nicole Harper (with the hat) and Carolyn Lanza sample water quality in the restored habitat. Photo by Jeremy Pike.Going native

The next step will involve planting native species. Thriving native plants—which would minimize invasive species recolonizing this area—are key to the restoration effort.

Alicia McAlhaney, along with Kelly Daniels, sloshed through the wetland’s boundary with a GPS, uploading the data points to make a map. Then, she and her partner were meant to randomly select areas to test for soil types so that students could plant native species where they would flourish.

Quickly McAlhaney discovered that, because the area had once been agricultural, the soil was uniform—but moisture levels were not. This made additional soil sampling unnecessary, and McAlhaney and Daniels adjusted their project. McAlhaney realized that drones would be the easiest way to map dam seepage throughout the year. Pike has put in the request to Clemson and is waiting for approval.

“I like hands-on research, which is why I got involved with Creative Inquiry,” McAlhaney says.

She discovered, through the project, that she wants to work outdoors where “every day is a different experience.” McAlhaney, who scored a summer internship with a forestry management company near her hometown, intends to continue her restoration research in graduate school.

As for the stream team, they measured how the vegetative team’s efforts affected water quality. Mostly, the students needed to determine if chemicals from the treatment sites leached into the water, if the goat fecal matter contaminated the water, and if the plantings were bringing back native animals. The undergrads did this by monitoring bacteria counts, pH, conductivity, turbidity, and dissolved oxygen, and by counting and categorizing the visible macro invertebrates, or as we commonly know them, bugs.

This testing, with the exception of the bacteria counts, all happened on site. The students took water samples from three sites (upstream, at the restoration area, and downstream from it), tested them, and packed out the dirtied experiment water in a bucket. For the bacteria counts, they brought water back to the lab, mixed it up into cultures, incubated it, and then looked for bacteria such as E. coli.

Brett Kelly, a self-proclaimed “fish guy,” has been involved with the Hunnicutt Creek project from the very beginning. A freshmen then, he’s now going onto his junior year. As part of the stream team, Kelly monitors insects and now amphibian communities.

So far, so good

To sample the invertebrates, the students would disturb areas upstream and let the current sweep the insects into the D-nets, which Kelly describes as a “three-foot broom handle with a net on it in the shape of an uppercase D.” Kelly then dumped the bugs into a tray, picked them out into egg cartons, and identified them. The purpose? To count the varieties of stream-dwelling insects sensitive to water quality. The more sensitive insects, the better the water quality. And so far, it’s looking good.

Recently, Kelly has begun documenting the amphibian population. Beside the stream, the students have created artificial frog and salamander habitats using PVC pipe and a cover board. Kelly stops by the sites and notes if they’re occupied. So far, every time he’s visited, he’s found tree frogs happily lodged in the PVC tubes. But, he says, “We haven’t found any salamanders under the cover board. It doesn’t mean they aren’t there. It just means they’re not using the cover boards.”

These undergrads, who cannot say enough about the benefits of Creative Inquiry, tell me that they’d like fellow students to become more aware of the Hunnicutt watershed. Kelly calls on the campus community to understand how littering affects Clemson’s wildlife and aquatic communities.

“Until my sophomore year, I didn’t even know this area existed,” McAlhaney says. “So, for it to become an open area, with park benches and tables, and for the students to be able to see the beauty of campus, that would be a top goal to me.”

Calvin Sawyer is an associate professor and Donald Hagan is an assistant professor, both in the College of Agriculture, Forestry, and Life Sciences. Jeremy Pike is an associate scientist in Department of Forestry and Environmental Conservation. Gary Pence and Alicia McAlhaney are seniors, and Brett Kelly is a junior. Additional undergraduates involved in the research include Bryanne Sidwell, Donald Mcdaniel, Carolyn Lanza, Rebeckah Hollowell, Johnson Dorn, Carly Basinger, Kelly Daniels, and Stephannie Allen. Sources of funding include the Clemson University Experiment Station, Clemson University Facilities, the South Carolina Exotic Pest Plant Council, and Clemson University Creative Inquiry initiative.