Selling soap and saving souls

Jeff Worley

How white filmmakers misread black audiences in the early days of film.

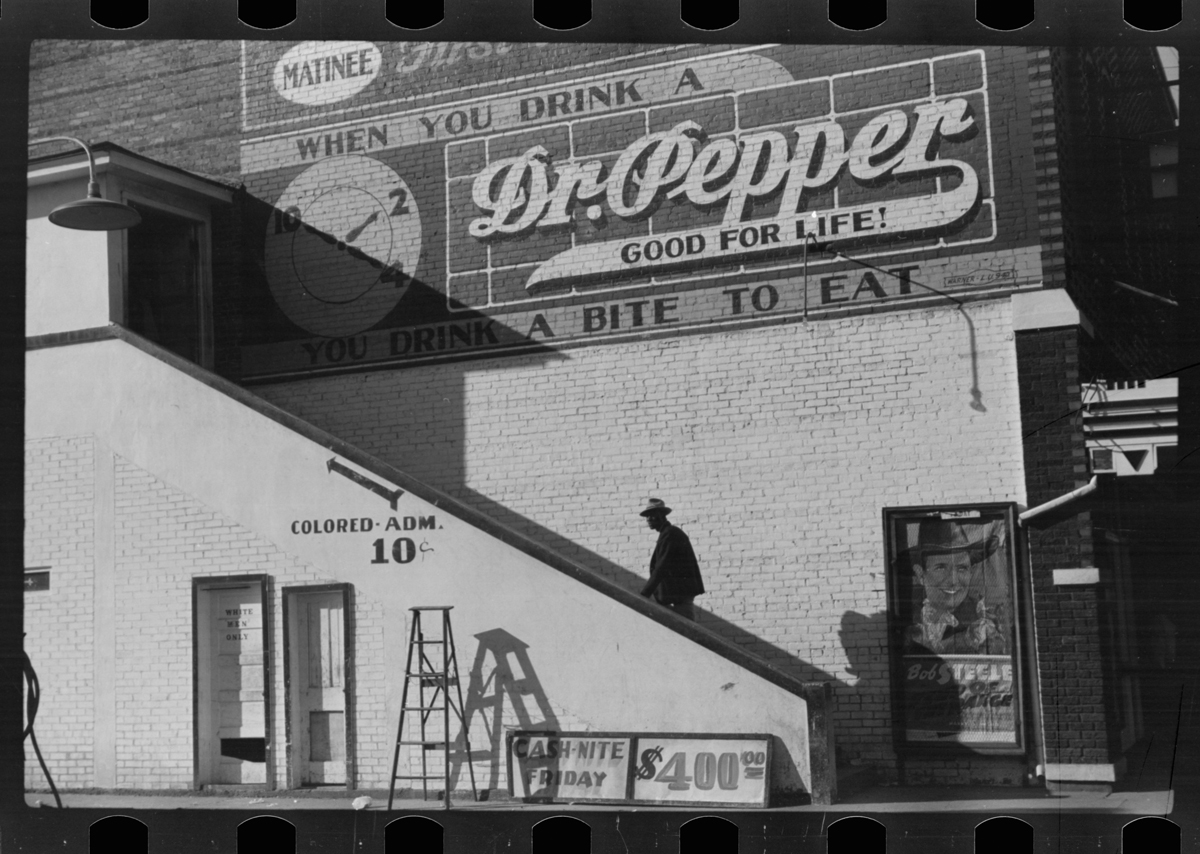

On a Saturday afternoon, a man climbs the back stair to a balcony seat at a movie house in Belzoni, in the Mississippi Delta. Photo by Marion Post Wolcott, 1910-1990. Library of Congress; The Crowley Company.

This caution to filmmakers interested in producing motion pictures for black African audiences comes from South African director Rudi Meyer in a 1986 interview. And according to history professor James Burns, this belief about the inability of Africans to understand movies dates from the early twentieth century, when British filmmakers brought movies to their African colonies.

But first things first: Why make films for black African audiences at all? Were the British keen on entertaining the colonials?

Burns laughs at this question.

“The films, beginning in nineteen-twenty with Unhooking the Hookworm, were strictly educational,” he explains. “They were funded by the Rockefeller Foundation and focused on trying to eradicate disease (encephalitis, venereal disease, malaria), instruct the Africans in modern farming techniques, and teach women to do small-scale manufacturing projects so that the household economy wouldn’t be entirely reliant on crops.”

In bringing these films to African colonials, the British Home Office in London was part altruistic and part capitalistic, Burns adds. The colonies were huge and easy sources of revenue for the British, partly because of the low capital investment in these far-flung land holdings. The challenge was to educate the peasant farmers without spending much to do it. Movies, the government thought, might be the answer.

But did African audiences get the message?

“Since the nineteen-twenties an army of filmmakers, academics, journalists, missionaries, and educators have attempted to measure the abilities of Africans to make sense of motion pictures,” says Burns, a specialist in African history and the social history of film, “and these groups have focused on several key questions. Could Africans be taught to understand the ‘language’ of the cinema? Were they particularly susceptible to motion-picture images? Did African audiences inevitably accept action on the screen as a literal depiction of reality or could they be taught to distinguish between truth and fiction?”

The answers to these questions involved high stakes, Burns points out. “These analysts represented groups committed to nothing less than transforming African societies and, though their agendas ranged from selling soap to saving souls, they shared the common hope that motion pictures might prove an efficient and potent tool for influencing the thinking and behavior of African audiences.”

Burns says that the first recorded experiment into African film literacy was conducted in the early 1920s, when William Sellers, a medical officer with the Nigerian government, studied the reactions of Africans to British documentaries. Sellers produced a film called Anti-Plague Operations in Lagos, to show Nigerians how rats spread contagion, and over the next seven years he made fifteen similar films.

Through his observations of Africans who watched these films, Sellers concluded that African audiences were clearly confused by the sophisticated techniques employed in most motion pictures of the time. So he instructed the actors in his films to move very slowly and make their actions simple, to basically dumb everything down. Sellers also used the most direct camera angles and as few potentially distracting characters and props as possible.

The chicken incident

“Because Sellers’ work influenced a generation of filmmakers, it’s worth examining how he arrived at these conclusions,” Burns says. “And we start with what African film scholars call ‘the famous chicken incident.’” Burns says that Sellers determined one of his rules after several members of an African audience expressed an intense interest in the activities of a chicken in one of his early productions. Sellers did not remember filming the creature, but after a second viewing, he found it running off camera, startled by one of the actors.

In Tropical Hookworm, a 1936 British film, a barefoot African man learns how worms spread disease. Director Leslie Notcutt largely endorsed William Sellers’ arguments that illiterate African audiences required a different set of rules from those of Europeans. Courtesy of Colonial Film.

“From this incident Sellers deduced that the audience noticed the chicken because of its position at the base of the screen. African audiences, he decided, ‘read’ the screen from bottom to top, rather than focusing on the projected image as a whole. He concluded from this one incident that the eyes of illiterate people fasten their gaze onto any movement in the scene to the exclusion of everything else in the picture.”

A second incident similarly added to Sellers’ developing “grammar” of colonial cinema, Burns says, this one starring a giant mosquito.

“Sellers recounted some Africans’ reactions to his malaria film, which included full close-ups of mosquitoes in the act of sucking blood, but when the film was shown, the results were disastrous,” Burns says. “Viewers became alarmed and inquired about the country where the people had to contend with such wicked-looking, gigantic monsters and remarked that they themselves were very fortunate to have mosquitoes which were quite small and comparatively harmless.”

From this incident Sellers concluded that African audiences accepted what they viewed literally and, therefore, filmmakers should avoid any tricks that might confuse or disturb them. Sophisticated techniques such as panning, flashbacks, and quick cuts were out for African audiences, he concluded.

Though Sellers was the most prolific and influential filmmaker during the early days of movies in Africa, other filmmakers were quick to posit various filmmaking principles based on scant evidence.

“Along with educational films about disease and hygiene, the British made quite a few films focused on farming techniques because, well, it was in their financial interest that the colonials be successful farmers,” Burns says. “During one of these films, which stressed the importance of what was clearly onerous contour-ridge digging, several of the men watching the film got up and left. The filmmaker’s conclusion: Their primitive minds couldn’t understand it. But the Africans understood exactly what the British wanted them to do; they just didn’t want to do it. That’s why they walked out.”

The consensus among at least two generations of filmmakers— that Africans didn’t and couldn’t get the language of cinema and that they were simpleminded as well as literal-minded—emerged from small sample sizes and a lack of understanding of the moviegoers’ cultural history and beliefs, Burns concludes.

It’s extremely likely that some of the stories about Africans’ failures to understand film are apocryphal, he adds, particularly since the specifics of the incidents are rarely given. And even if true, he believes they are certainly open to alternate interpretations.

“In discussing the reaction of the audience to the mosquito on the screen, Megan Vaughan, a historian at King’s College in Cambridge, pointed out that Sellers and his successors never considered that such comments might have been meant ironically,” Burns says. “My own experience in Zimbabwe suggests the strong likelihood of this possibility.”

A major reason why these assumptions about African audiences became so entrenched is because they carried such heavy political freight, Burns says.

“The belief that African audiences had limited capabilities reinforced a broader colonial stereotype regarding the intellectual state of Africans,” he explains. “Especially in southern Africa, where white minorities sought to cling to power forever, these assumptions remained solid and unshakable because they served to legitimize the perpetuation of settler control. In questioning the abilities of Africans to comprehend modern media, it’s a short step to conveniently conclude that these Africans were incapable of participating effectively in a technologically sophisticated, democratic society.”

Jump cut to Clemson

Burns came to his research into African film through his study of African history in graduate school.

“In grad school in the mid-nineties I read a story about how the government in Southern Rhodesia had been making movies strictly for African audiences since the nineteen-twenties, and the focus of the article was the challenge of making movies for people who’d never seen a movie before.” Burns, who admits to a lifelong love affair with movies, then got a Fulbright Grant to study the history of moviemaking for African audiences in Zimbabwe (Zimbabwe gained its independence from Southern Rhodesia in 1980). In 1998, after earning a doctorate in African history at the University of California, Santa Barbara, Burns joined the faculty at Clemson.

James Burns outside the old Clemson movie theater, now a sportswear shop. In communities across the country, the local movie house was once the hub of popular culture. By studying the films, the venues, and their history, Burns and his students investigate the values and beliefs of the time. Photo by Craig Mahaffey.

“When I moved to South Carolina, I started doing research on early moviegoing by blacks in this state and was struck by how similar their experiences were in the nineteen-twenties and nineteen-thirties to those of Africans in Southern Rhodesia. Both operated with a rigid racial caste system where blacks were relegated to the status of second-class citizens. In order to see a movie, blacks in South Carolina were made to sit in a ‘Colored Only’ balcony or in a segregated part of the theater. And in South Carolina and Southern Rhodesia, blacks faced identical forms of censorship.”

A case in point was the early, jerky footage of the 1910 World Heavyweight Championship fight between Jim Jeffries, “the great white hope,” and Jack Johnson, a highly touted black boxer. Johnson won, and this outcome triggered race riots that evening in twenty-five U.S. states and fifty cities, from Texas and Colorado to New York and Washington, D.C. Eight blacks and five whites died in the riots, and hundreds more were injured.

“Some of these so-called riots were, in actuality, simply joyous celebrations by blacks, who felt Johnson’s great victory was a victory for racial advancement,” Burns says. “But there’s no doubt many whites felt humiliated by the defeat of Jeffries. A number of states, including South Carolina, banned the Johnson-Jeffries film for viewing by blacks, thinking it would be self-congratulatory or incendiary. In Southern Rhodesia, Africans were also not allowed to see this film.” Other films, most notably D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation, were also banned for blacks in South Carolina and Southern Rhodesia, though, as Burns points out, the film was promoted to white audiences.

“Until after World War II, blacks faced these obstacles in participating in what was clearly the most important communications media ever invented,” Burns says.

Sending students to the movies

In addition to his own scholarship on the history of moviegoing in South Carolina, Burns began offering a research seminar at Clemson last spring that focuses on this topic. His students choose a city or town in the state and work to reconstruct its moviegoing history through a variety of primary sources that include old newspapers, maps, journals, and interviews with elderly members of the community.

“The idea is to use the then-new and unique form of urban space, the picture palace, as a window into the important social and economic trends that swept the state between nineteen-hundred and nineteen-forty,” Burns says. “The students will end up with a local history of moviegoing that is a microcosm of a much larger story.”

A key part of the story is the experience of African-American audiences, Burns says. Conventional wisdom says that blacks didn’t go to see movies in great numbers before World War II, but this was the same assumption scholars made about African audiences in the colonial era, which Burns’ research has shown was inaccurate.

“So this is where my research dovetails with the research projects of my students. But finding evidence of early black moviegoing is challenging. There isn’t much of a paper trail to follow—very few black theaters advertised—and oral histories are sometimes hard to come by since movie patrons from the early days of moviegoing are now in their eighties and nineties.”

Although his current students haven’t completed their projects yet, there have been some interesting and surprising findings.

![aiken_paper_day_1[1]](http://glimpse.clemson.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/aiken_paper_day_11-1024x1024.jpg)

On the entertainment page of a February 3, 1924, newspaper from Aiken, South Carolina, readers could find an ad for Enemies of Women, a 1923 silent film directed by Alan Crosland and starring Lionel Barrymore, alongside an application for membership in the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan.

Kathleen Brand, who was in Burns’ fall seminar, says among her early findings in Camden, South Carolina, is that to get people to come to their theater, owners would advertise raffles in the town newspaper, or various contests with prizes.

“My favorite is the contest for the prettiest girl,” Brand says. Another interesting and popular event at the Camden theater was “bank night,” a cash giveaway that built up until the name of a person in the audience—you had to be present to win—was drawn. Yet another trick to get people to the theater was that local filmmakers would shoot footage of people in Camden and then show the films in the local theater so that people could see themselves on the big screen. “Apparently these creative strategies, promoted in the local paper, worked,” Brand says.

“The theater advertisements are interesting,” Burns says. “While white theaters advertised an array of ‘quality’ films, the black theater ads featured almost exclusively B-movie Westerns and serials. This is consistent with what I found in Africa—that the high cost of renting first-run movies, combined with the familiarity of the Western genre, made the cowboy film a staple of black moviegoing until World War II.”

Some of the students are uncomfortable with what their studies are revealing to them about their hometown histories, Burns says. “They are shocked to learn about the marketing of The Birth of a Nation in South Carolina towns, the banning of that film and others for black audiences, and the segregation of movie audiences, which continued long after it had been made illegal.”

In her research, Alli Lane, who was also in the fall seminar, discovered a racial incident that took place at the segregated American Theater in her hometown of Charleston during the civil rights era.

“During a movie being shown to a mixed-race audience, with whites on the first floor and blacks in the balcony, racial slurs were made and fights broke out,” she says.

The students’ discoveries so far are unique to the cities and towns they’ve chosen to research but, Burns says, there’s one common result.

“All of the students who have done this detective work have discovered how much more significant and central moviegoing was to social and cultural life in the first half of the twentieth century as compared to today. For me, the fun of this project has been to watch the students get excited about the history of their hometowns. The movies are their window into this history, and these students have used a remarkable combination of ingenuity and energy to go deep into their community’s past.”

James Burns is an associate professor in the Department of History in the College of Architecture, Arts, and Humanities. Jeff Worley is a freelance writer and poet who lives in Lexington, Kentucky.