Don’t be afraid

Neil Caudle

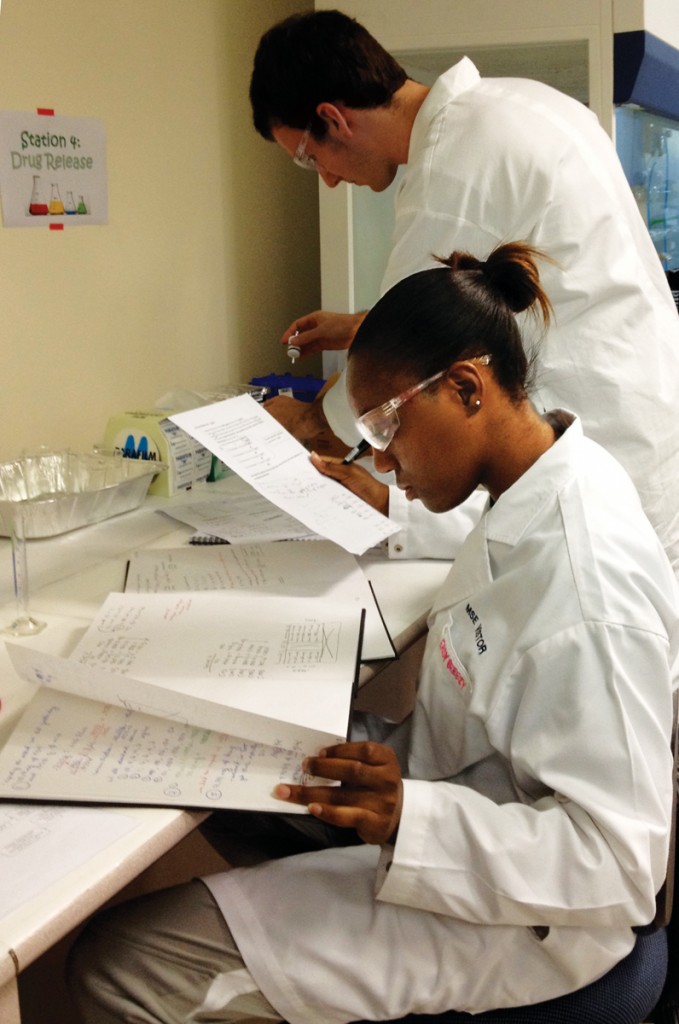

Bria Dawson checks lab notes at the Nanyang Technological University in Singapore, where she and eight other Clemson students worked on a treatment for retinitis, an eye disease. Scott Cole, a senior bioengineering student from Clemson, works alongside her on a separate project. Photo by Cheryl Jennings.

One day last summer, Bria Dawson walked into a clinic in Singapore and watched a patient take a needle in the eye.

“He was an older man, about sixty, and he was in a lot of pain,” she says. “He let out a cry that was awful to hear. I didn’t want to see that happen to anyone ever again. I didn’t want to see a needle go into somebody’s eye again. For me, it was motivation.”

Motivation because Dawson and several of her classmates from bioengineering were in Singapore looking for a way to replace the needle with something much gentler—a clear film of thin, biodegradable plastic that could deliver the right kind of drugs to the eye. “You could think of it as a kind of contact lens,” she says. “The goal was to have it gradually release the drug over a six-month time span.”

The two drugs involved, known as Val and Gan, control retinitis, an inflammation of the eye caused by human cytomegalovirus (CMV). People infected with HIV are especially susceptible to CMV when their immune systems fail to suppress it. Without treatment, patients with severe CMV retinitis go blind.

So the goal was clear, the motivation was strong, and the stakes were high. But creating a lens to deliver a controlled dose of Val and Gan was no small task. And the team of scientists assembled to work the problem? Four undergraduate students in bioengineering at Clemson. They had only eight weeks to get the job done.

“When I was in high school, I loved math and science, and I wanted to be a doctor, but I never imagined that I would ever go to Singapore and do anything like this,” Dawson says. “Once you’re there, and you start seeing results, you realize, hey, maybe this can work. And then you can do things you never thought were possible.” Dawson was part of a summer research program led by Frank Alexis, assistant professor of bioengineering. Last summer, Alexis took Dawson and eight other students to Singapore for research at Nanyang Technological University (NTU), where he had earned his Ph.D. Using his contacts there, Alexis arranged for teams of students to work on three projects in one lab under the supervision of NTU scientists. The goal was not just to let students conduct biomedical research; it was also to shift their learning into high gear.

“When we take the students overseas, their level of learning increases rapidly,” Alexis says. “They have to adapt very quickly, which is what usually happens with graduate students when they move to a new campus and work in a new environment. Our students are getting this experience as undergraduates.”

Soon after they landed in Singapore, Dawson and her three teammates— Kali Luffy, Cheryl Jennings, and Even Skjervold—went to work in the lab. First, they had to figure out how detect the presence of each drug in the film by determining the wavelengths of the drug compound’s fluorescence. This involved multiple experiments with various chemical buffers and drug solutions. Eventually the team found the right wavelengths for excitation and transmission—reliable markers of a compound’s reaction to light.

The sweet, not the sugar

The experiments were a success, and the team moved on, testing various polymer solutions and doses of the drugs. They used a device called a knife caster to flatten the mixtures into very thin films, dried the films, punched out the lens-like circles, and tested rates of drug release. But as the team tried to suspend both drugs evenly in the polymer, they ran into trouble. One of the drugs, Gan, precipitated out of the polymer, leaving cloudy white patches on the surface. None of the solvents the team tested kept Gan in suspension. Because of the problem with the solvents, Dawson says, the lenses released the drugs too rapidly, over fifteen days rather than six months.

“The drug should dissolve in the solvent the way sugar dissolves in your tea,” she says. “You want to taste the sweetness, but you don’t want to see the sugar.”

With more time, the team would have tested other solvents, and Dawson feels certain that researchers will find the right one. Alexis plans to take another group of students to Singapore this summer, and Dawson expects the next team to pick up where hers left off.

“We set up the foundation for the project,” she says. “We feel good about what we accomplished in such a short time.”

Building toward a career

Clemson’s collaboration with NTU in Singapore helps students prepare for a job market that is increasingly international, says Frank Alexis.

“A lot of companies have offices overseas, so knowing something about other countries can give you an advantage,” he says. “Also, if you work in a big company today, there’s a good chance you will work with people from China or Singapore or somewhere else. If you’ve worked in other countries, you’re a more valuable employee.”

The program is especially useful for students interested in medicine, Alexis says. “We have many students going to medical school, and research can make a difference. Our students have had good success on the entrance exams, and medical schools are looking for the kinds of experience we provide.”

The Clemson/NTU collaboration, which began in the summer of 2011, has landed a number of student fellowships and scholarships from outside sources such as NTU and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. Several students from the program, including Bria Dawson, have received awards for student research and for poster presentations.

“Students get more out of this experience than a course credit,” Alexis says. “They are broadening their perspectives and building their résumés.”

Not just one guy alone

She also feels good about the experience of working as part of a team. “I used to think science was one guy alone in a lab coat watching a Bunsen burner all day,” she says. “But science is more about the team. I think a lot of women like to work in teams. We don’t say, ‘Hey, I’m this macho guy who’s going to do everything himself.’ We know our strengths and weaknesses, and when you find a team with different strengths, you can put them together and accomplish a lot. And when you get frustrated, you have a partner there to help you, a companion to keep you focused.”

Dawson also got a chance to test herself in cultures very different from her own. Venturing out into Singapore streets, she marveled at the people’s fascination with technology. Everyone she passed was operating a high-tech gadget. And yet people were friendly, she says, and she felt safe and welcome. From Singapore, the team made side trips to Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia. Dawson thinks of herself now not only as a scientist but as a citizen of the world, with a responsibility to serve. “As scientists, that’s one of our jobs,” she says, “to help others—in Asia or wherever they are.”

The combination of science and travel has emboldened her, she says, to strive for bigger goals. She plans to earn a Ph.D. and work as scientist, first in industry and then in academe. Asked how she would advise a high school student considering a study of science in college, Dawson sums it up this way: “Don’t be afraid. It was my first time abroad and my first time conducting research, and the experience changed my life. My confidence is much higher now. I feel like I can do anything.”

Bria Dawson is a senior majoring in bioengineering. Frank Alexis is an assistant professor of bioengineering in the College of Engineering and Science.